“And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.”

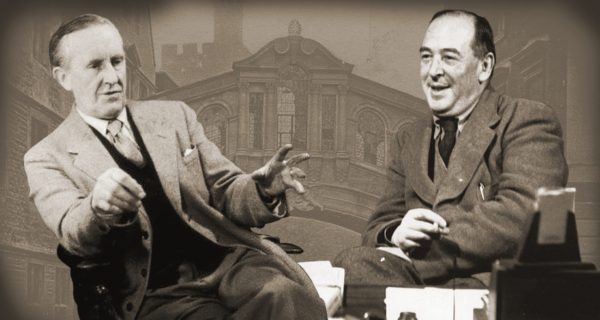

There is good fantasy and bad fantasy. Anyone who has watched fantasy movies or read fantasy books knows that all fantasies are not created equal. What makes art in general, writing in particular, and this genre of literature specifically good or bad? Is it reasonable to call art like fantasy good or bad in the first place? I believe it is; and as to the question of good and bad fantasy, I trace my knowledge of this judgment to two men who understood it better than most: J.R.R Tolkien and Jack Lewis.

First, both of these men held to a traditional worldview and Christian orthodoxy. This was certainly going out of style in Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries, and both Lewis and Tolkien must have felt like two of the last sane men standing in Oxford during the time. In fact, we read that Lewis described himself as a dinosaur in one of his most famous lectures. However, it is three of the major tendencies of this dinosaur worldview that make their writing good: first, is that truth exists; second, truth can be known; and third, God is the author of it.

Secondly, both Dr Lewis and Professor Tolkien created their stories out of and in harmony with their beliefs. This unification and holistic approach to the person was at odds with the public/private sphere dichotomy of the new modernist. The concept of compartmentalization was unthinkable to both men. The modern idea of keeping faith in the personal sphere and out of the public life would have been as foolish as telling the sun to only give light but not heat. For Jack and Professor Tolkien, who you are shapes what you do, and what you do is who you are. All of life is sacred; and therefore being in the image of God means living as the image of God. Lewis and Tolkien did just that in their walk and their writings. According to Tolkien and Lewis, good art–in this case fantasy–comes from right beliefs; and right beliefs are best when they are practiced.

Finally, the specific type of art must be created well and possess a high quality. There are, of course, several requisites to creating good art. The first is knowledge and understanding. Few men knew more about the world of literature, myth, and language as Lewis and Tolkien. Both men understood their craft intellectually and through personal experience. After all, it was through their deep understanding of Myth–specifically the Norse and other Pagan myths–that convinced Lewis of the true myth of the gospel story and converted him to Christianity; from the modern hero and legend tales of paganism, to the peculiar just-like-something-that-would-really-happen roughness of the gospel story. It was not a set of new beliefs that converted him, but learning how to read the greatest true story the right way.

The second requisite to creating good art is sub-creating. For Lewis and Tolkien, it is not only knowledge and skill that make for good fantasy, but that fantasy has a right way to be, and an end that makes it good or bad. This is best accomplished through sub-creation. What do I mean by sub-creation? God created humankind in his image. God created humankind to bear his image. Humans are most blessed when living according to their nature, or virtue, and virtue is the greatest good. Therefore God is the greatest good and bearing his image is our greatest blessing; but what does it mean to bear God’s image? It means to live a life that reflects who God is so that he can be known and glorified. One of these great reflections is sub-creation.

God created us to be creators. God created us good, so we could create good in our art and literature. It was Lewis and Tolkien’s conviction that the greatest and therefore most good literature was that which best and most closely resembled the creative works of God. We see this all throughout both men’s writings. God can be known and experienced through natural theology. Therefore, high myth like The Lord of The Rings makes use of a world very close to our own. It is a natural world of rocks, lands, waterfalls, men, horses, stories, and its own mythology.

Lewis’s world is one of animals, lamp-posts, snow, boys, girls, professors, big lonely houses, and death. Of course death and other natural things we experience in our own world are the same things we experience in Lewis’s and Tolkien’s, because it has been created by the creators of those stories in a lesser way than the Creator has created ours. Much can be known and experienced and lived in this natural world, but always on the outskirts of this natural theology is the Story. A bigger story. The real story. One of a time before time. A creation, fall, struggle, redemption, consummation and joy. A world where there is more than meets the eye, and home is a place we are going, and perhaps beyond the wardrobe and over the endless seas we shall find the shire and say: “What a good story.”