As young children, my older brother and I watched the original Star Trek series on Saturday mornings. We were not big TV watchers as a family, but Star Trek was special. To make it even better, it was the local PBS that aired Star Trek, presenting it free of all commercials.

Every Saturday, Todd and I awoke very early and watched the rerun for that week. This would have been around 1975, almost a decade after the show first aired. After each episode, Todd and I would talk, always mesmerized by the possibilities of space, life, and a billion other things. How much of the galaxy had this crew explored? Were they the modern Lewis and Clark? What happened when someone transported from one place to another? How smart were the computers? Were the Klingons the Soviets and the Romulans the Chinese? Or, maybe the other way around? Why did we only see the military aspects of Starfleet? What about the colonists, the pioneers? How did time travel work? If the Enterprise found itself sent back to Earth, why did it happen to arrive the same year the show was being filmed?

Pretty serious stuff for an eight-year-old sitting with his much admired thirteen-year-old brother.

I had no idea at the time, but the show’s founder and creator, Gene Roddenberry had actually described Star Trek as a “wagon train to the stars” when he first shopped it to studios. It would be set, though, on the space equivalent of an aircraft carrier, a mobile community as diverse as Gunsmoke’s Dodge City, he continued in his show treatment. The crew, roughly 203 of them, would be as diverse as possible, asserting that racial prejudice and ethnic strife would be things of the past in the non-specified time of Star Trek. Only later did the show writers decide it took place in the 2260s. From its beginning, however, Roddenberry’s Star Trek represented a brash Kennedy-esque liberalism, a confidence that America could teach the world the principles of civilization, tolerance, and dignity.*

And yet, this would not be merely a western in space. Roddenberry recruited some of the finest science fiction and horror talent available in the 1960s including D.C. Fontana, David Gerrold, Robert Bloch, Samuel Peeples, Richard Matheson, Theodore Sturgeon, and Harlan Ellison.

Though much of Star Trek now appears campy, especially with its poor attempts at humor and terrible costumes (especially for the aliens), there is no doubt the team making the show took science fiction and its ideas very seriously. Themes of natural rights, equality, imperialism, personality, racism, religion, history, culture, and much else important in life appeared throughout the original seventy-nine episodes. It must be noted, though, that I do not remember my young self thinking poorly of the special effects.

Sharing my favorite scene—Captain James T. Kirk fighting a gorn—proved way too much for my kids. Dad, my oldest daughter asked, “Why is Captain Kirk fighting a guy in a rubber suit?

And, of course, my brother and I loved all of the fight scenes. Who would not want to follow Kirk into battle? The guy was made for serious leadership. Plus, the over the top fight music was simply incredible. I can still recall the entire theme instantly, while poorly visualizing the yellow-shirted Kirk kicking, punching, and rolling. I am really not sure how many times I tried to perfect Kirk’s jump kick maneuver as a child. It is amazing I am not more damaged than I am. Thank the good Lord I only tried it upon invisible and imagined foes. I was not so fortunate when it came to the Vulcan nerve pinch. Practice with this—especially after sneaking up on members of my family and trying it—really only resulted in sore muscles and hurt feelings.

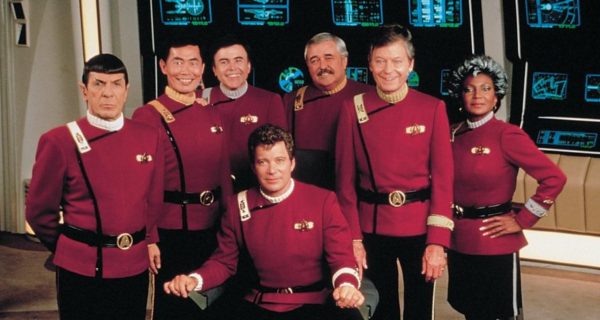

When it came down to the quick of it all, though, it was the interaction of the personalities—the characters of Kirk, Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy, and “Scotty,” especially—on the show that meant so much to us.

Star Trek demonstrated, over and over, I think, that real heroism comes not from individualism, but from friendship. These guys on that little screen not only loved one another, but they each bettered the other. Spock needed Kirk, and Kirk needed McCoy. McCoy needed . . . well, everyone.

When Star Wars came out in 1977, I loved it. But, in no way did it compare to Star Trek, at least to my way of thinking. I knew that Star Wars was essentially science fantasy, while Trek was real science fiction—again, as my young mind saw it. Luke Skywalker and Han Solo were great, but for real fantasy, I turned to J.R.R. Tolkien. For sci-fi, I wanted Kirk and Spock and a whole host of science fiction authors from Isaac Asimov to Arthur C. Clarke.

When Star Trek: The Motion Picture came out, my mom took me to an opening show in Kansas City—then, the major metropolis in my life. We saw it right before Christmas, 1979, and I was completely blown away. The scale of it reminded me of 2001, and the return of NASA’s Voyager spacecraft for a science loving kid was a dream come true. To top it off, the movie ended with the creation of an entirely new form of life, an incarnation of man and machine. What was not to love? This seemed so much better than the blowing up of a Death Star!

Rewatching it quite recently, it hit me what a beautiful movie it is. Many critics have complained that it simply failed to have enough action, that it demanded too much of the viewer. This is all probably true, and these are also the reasons I like the movie so much, even as a 12-year-old. Star Trek: The Motion Picture is a film that allows one to consider possibilities, to realize the immensity of the unknown, and to contemplate the potential dangers of space travel. The movie demands immersion.

Nothing prepared me, though, for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. I saw it only days after my eighth-grade year ended. It hit me hard, very hard. The film is the best of the best when it comes to Star Trek. Shakespearean acting flies freely, dialogue from Herman Melville comes equally fast, and the plot moves as dramatically as the best war movies made prior to Apocalypse Now. Realizing how quickly they are aging, the crew encounters a late twentieth-century genetically created superman, a Nietzschean tyrant bent on absolute revenge for Kirk’s actions in the original episode, “Space Seed.”

Unlike every one of the later movies, Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan avoids camp, managing to tell a story as serious as Star Trek: The Motion Picture but with immense humanity of friendship, community, and sacrifice. William Shatner (Captain Kirk) is especially at his best. The scene in which he allows his arrogance to bring death upon his crew and the scene in which he realizes Spock has sacrificed himself for their mission are two powerful and emotional scenes. For better or worse, I am sure I have watched The Wrath of Khan more times than any other movie in my forty-six years. I have it memorized—dialogue, scenes, and music. Still, the movie has never become so familiar to me that these two scenes just described do not fail to move me to tears.

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock had some fine moments, but it is clear that the crew would never again reach the heights of Wrath of Khan. Star Trek IV returns to sap and camp, and the movies really become uneven from that point forward. Yet, no one could deny its popularity and money-making ability. Thus far, there have been a total of five live-action television series, one animated series, and ten movies set in the original universe. Two additional movies—though essentially action films in the vein of Star Wars—have appeared in the rebooted timeline. One can also find Star Trek toys, comics, and books everywhere and anywhere.

Star Trek has permeated our consciousness as much or more than any other manifestation of pop culture. Why? Several reasons, but only two need be mentioned here.

First, I am convinced its timing was most fortuitous, coming as an optimistic Kennedyesque frontier vision just as the 1960s soured into the imperial horrors of our policy in southeast Asia and with the subsequent dramatic loss of American confidence.

Second, and more importantly, the show was about friendship, community, and sacrifice. Art, drama, and theater might very well mock or forget such themes in cynical and decadent ages, but such ideals can never be utterly destroyed.

Kirk needed Spock, and Spock needed Kirk. The same was just as true for Scotty and McCoy. Individually, they succumbed to terrors, errors, and arrogance. As a group of friends, playing off of and leavening the strengths of the other, they were unstoppable.

There are not just good lessons for the moment; they are transcendent ones.

—

(Originally published on The Imaginative Conservative; for more writings from Mr. Birzer, visit his blog Stormfields)