~ by Alexandra Jezierski

“We are sorry to announce that the 9:08 am train to Oxford is delayed by twenty-one minutes.”

Gabriella heard the announcement with a groan. She shoved her backpack off her back and planted herself down on the station bench. Flipping open the book she was to have read for her Inklings class in an hour, she found her bookmark at page seven. Fingering the two hundred pages left, she grimaced. A quick skim-read would have to do.

“Excuse me.”

She looked up. The man whom she was sitting next to had his face turned towards her – or at least what she could see of his face from under his grey Ascot top hat. A wrinkled face, with white sideburns coming down to a white tuft of beard, and blue eyes.

“You dropped your ticket.” He said it with bemusement, almost jovially – as though it were funny that he should find it. He was holding out an orange railway ticket.

“No – no I have it.” Gabi reached into her backpack pocket to show him. “It’s here – zipped – so it’s impossible for me to ever lose,” she explained cheerfully. Her hand rummaged through the pocket. Again she rummaged harder. Nothing? “I just bought it – I put in here. I couldn’t have lost it…” She stared up at him, thinking.

He lifted his hand, nodding at the ticket still in it. “Your ticket.”

Incredulous, she looked him in the eyes, slowly put out her hand, and took the ticket from him. How the ticket was not in her backpack when ten minutes ago she had put it there, she could not guess.

Thanking him, she returned to her book. She could hear the man humming an old tune to himself with an occasional mutter of impatience about “useless trains around here.”

The train whisked up, and shouldering her backpack, she saw the old man, twirling a black umbrella, step into the next coach of the same train.

As she settled in a window seat, excitable discussion across the aisle made her look over. A group of men in a set of six seats, facing each other, were talking in loud voices. All their focus was on some papers scattered on the central table, over which their grey heads leaned as they exclaimed to one another.

Their images reflected faintly as she watched the sheep fields out the window, enclosed by mossy stone fences, their greenness made almost neon by the misty rain that had started. Snaking streams with floating sticks, rolling hills, and ivy-covered trees flew by as the train whisked through. Glued to her window, under her breath and just faintly enough that the other passengers couldn’t hear, she sang Celtic songs that melded with the lyricism of the landscape. What a poetic phrase, and she had thought of it herself. And what a poetic existence, when watching the world fly by rhythmically, underlined by the low, subconscious rumbling of the train on the metal rails, letting yourself fall to a dreamy state where you feel part of the World Through The Window and yet you are part of the World Inside The Train, only looking on as the World Through The Window whirls by.

“Tickets to Oxford,” an attendant called out.

Gabi broke from her reverie reluctantly. She handed him her ticket to punch.

The attendant scrutinized the ticket. “Ah.” He scratched the stubble on his chin and looked intrigued. Then he cocked his head and grinned with a nod, tapping the ticket into her hand. “Out for an adventure?”

“Ye-es,” she said, scrutinizing him in return, and then her ticket. “OXFORD” – it was there in black ink, all capital letters. There was no question about the ticket being to the wrong destination. But why was the ticket more and more feeling like it had some suspicious air about it?

Pulling up at Oxford station, it was a relief to find it quite unchanged. Slightly old and slightly dirty, but familiar.

She whipped open her pocket watch necklace – class in five minutes! She ran through the streets, wiping the misty rain from her face, almost tripping over a pokey cobblestone as she turned into New College Lane. Dashing into her college and down the hallway, she finally stopped, panting, in front of the door. She tried the handle, but it was locked.

Was class cancelled? She stared at the blank door, sat on the corridor floor for several minutes, and finally gave up. With a final glance of confusion at the door (and frustration for the needless running), she left and walked out towards the library to at least finish her homework for next class.

Walking through St. Mary’s Passageway, she stopped a moment to admire the old twisted tree that had always reminded her of the tree whose wood must have been used to create the Narnian wardrobe. Its weirdly contorted branches and the way it leaned so heavily over the low brick wall behind which it grew, gave it an air of importance – as though it let you enter someplace different when you stepped under its branches. Whenever it rained, the bark looked black. Gabi liked it because it made the tree even more mysterious.

She stepped under its low, bare black branches.

Then in one moment, the tree sprang to life – tiny blossoms of pink unfurled.

Little green buds emerged on the very tips of the branches, and out of them pale pink points squeezed out, unravelling their petals. Then they rapidly multiplied – within seconds, the bursting of the tiny flowers spread through the twigs, through the branches, wrapping the entire tree in a glorious shroud of pink. It wrapped her into its magic canopy. The faint sweet smell of the tree mixed with the dank smell of the streets. Mesmerizing. And impossible.

It had thrown her so off-balance – the suddenness of it – that she stumbled a couple of steps forward – and was about to take a look from a distance to ascertain what she had seen as she stood underneath the tree – when she heard a terrible roar.

Gabi caught a gasp as her eyes met with the face of a Lion. His wide, fierce, gentle eyes looked into her. There was only his face – and he was a carving in a wooden door by the Passageway– but he was real! His mane shone of gold, not wood. He bared his teeth and roared again – it was a roar at once terrible and gentle.

“Good morning,” two voices said in unison.

Gabi sprung back. Two gold fauns, adorning the top corners of the door, had bobbed their heads and moved their metal gold arms to play a tune on their lutes. She had seen them before. The Lion, too, she had seen. She passed them every day that she went to the library to study. But they were always ornaments, and now –

“Ah. My friend.”

Gabi spun around at the sound of the familiar voice. The old man from the train station was standing across from her, his black umbrella shielding his hat from the misty rain, with a pleased expression on his face.

He tipped his hat quirkily. “You’ve finally made it. I was beginning to think you may have had the wrong ticket.”

“What ticket did you give me?” she spoke slowly, thoughtfully.

“Your ticket, of course. Your ticket to Oxford,” he chuckled, adding a note of reassurance in his second phrase. “Mm –” He twirled his open umbrella distractedly. Rain rolled down its side, splashing on her sleeve, but he did not notice. “With a touch of magic, perhaps.”

“Do you know about all – this?” She weakly waved her hand toward the lion on the door, the gold fauns (which were both now still), and the tree.

He didn’t answer. He just met her eyes solemnly and gave a short nod.

“You don’t know about – this.” He said the last in a hushed whisper, as though he were about to reveal something sacred. Putting his hand on her shoulder and the umbrella over both their heads, he guided her forward, towards a lantern.

It stood, solitary, in the middle of the passageway. Black and slender, with an iron-carved tip creating a sharp point against the grey sky. It was not lit, but it created a quiet centre, a landmark that felt at once familiar. Gabi knew it. She knew it from passing by every day, but she knew it in some other way, too, some way she did not know quite how to explain.

“I don’t understand -” She and the old man had stopped before the quiet dignity of the lantern. “I think I do know about this. But I don’t, at the same time. I know all these places. I see them everyday. But they’re so – so different. They’re real.” She looked up at him under his crookedly worn hat.

“Aha, that is because they were real all along – you were one of the only ones to know it. And you did not know that you knew it. Now you do.”

He leaned over and tapped the lantern with the tip of his umbrella. A light all of a sudden flickered, then flared up into a brilliant glow. A Lion’s roar from behind seemed to ignite the warm fierceness of the light.

They stepped into the world on the other side of the lantern. Everything looked the same. But the lantern gave everything there an aura of a slightly different world.

“There are some things for you to see. To the river, shall we?”

The misty rain had stopped as they walked, and the sun was pushing through the clouds. The old man folded up his umbrella and demoted its function to that of walking stick.

“Ah, and here we are. The Fellow’s old place.”

Gabi was about to inquire about who the Fellow was, but suddenly the view before her struck her dumb. They had passed through medieval cloister halls and were standing in a meadow, split by a curving stream, speckled with various figures. The figures, as they came into view, were of the most magnificent kind. Large, noble-looking centaurs were standing in the meadow. The sun had finally won over the clouds and its brightness, reflecting on the centaurs’ armour, made them blare with light against the dark of their skin and the chestnut of their horsehair. Dark-haired fauns were running about, some playing lutes, each emanating his own melody, yet all the melodies flowing into one single melody. A gryphon rose into the air, spreading out the heavy power of his wings with an easy lightness, just to duck back down and snatch a fish out of the stream with his huge beak.

Gabi was standing immobile, her hands clutched over her face in amazement, gazing with eyes that were filling with tears at the sheer magic of it, and the beauty, and the wonder, unable to absorb it all.

The old man settled himself in a tree trunk into which a seat had been carved, watching her enchantment with a smile that wrinkled the corners of his eyes.

She turned to him. “I never asked you your name.”

He pursed his lips bemusedly as though he had to think about it. “Jack.”

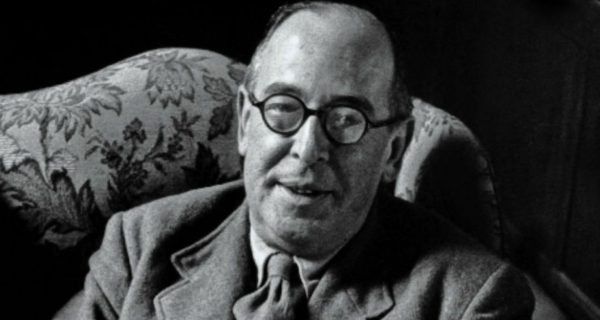

“Are you Jack Lewis? C.S. Lewis?”

“No, I am just Jack.” He crossed his legs, making himself comfortable against the backrest of the tree trunk. “Little Jack. One of the thousands of little boys who read about Narnia and believed in it. And one of only a handful who grew up and still believed in it.”

“Have you ever gone to Narnia?”

“Well, one day, I was twelve years old and it was raining. So I brought out my umbrella to keep me from the rain. I had taken the train to come into Oxford to get some sweets from the candy shop – and I was passing by the tree that you passed by today. A harsh yelling was ringing through the streets. There was a lady from the Establishment who wanted to have the tree cut down to make a new door for her office building. A little girl was begging her not to, telling her that she couldn’t. The men, three or four of them, were all ready with their axes to cut the tree down. It hadn’t bloomed for years and years. It was never going to bloom again. What was the use of a crooked dark tree like that? The girl said that if they cut it down, Father Christmas wouldn’t be able to come through on his way from Narnia anymore and he would be stuck. Two of the men were insisting that there is no Father Christmas, that it had all been a fabricated tale by her parents to keep her good, and the lady also told the little girl not to be foolish.

“The girl then burst out that even if they would pretend that Father Christmas did not matter, they at least had to save the dryad that lived in the tree. You see, the lady from the Establishment had just recently had a bridge built over the river. And whenever a bridge is built over a river, the naiad or river god who lives there is imprisoned forever. So it mattered a great deal that at least the poor tree nymph be saved.

“I joined the girl’s cause when I heard it. I learned that the door the lady wanted to make was to replace the old wooden door just down the Passageway – the door with the carving of the Lion. When I learnt that, I simply couldn’t not take a part in the matter. I told the lady that there is a Father Christmas, and that if she had any common sense at all, she would know that there are also flying horses and witches and fauns and a Lion, too. And dwarves. I looked her in the eye when I said dwarves, because she was very short. She was horrendously insulted and was just about to box my ears – when the voice of a kindly man reached my ears.

“The man took our side. He was the only grownup that did. He said it would not be fair to keep Father Christmas in the snow, and it would be far more agreeable to allow him to come to England, where it seldom snows and he could have a break.

“He insisted so intently against the cutting of the tree that the lady and the three or four men finally gave in. The girl – her name was Emmie – and I thanked him. But it was really the Lion that did it. I didn’t know it then. But when we left the man – he said his name was two funny names that sounded something like olive and staples – and he said to call him Jack – he winked at us, just as we walked past the twisted old tree. He had a sort of secret to share in his wink.

“Just as we stepped under the branch of the tree, something quite unlikely happened. The tree in a moment’s time burst into full blossoms, even though it hadn’t for years. A beautiful lady appeared – a dryad – clothed in a dress of pale pink petals, with green leaves in her hair, and she guided us through the passageway. We heard a Lion’s roar, and two fauns greeted us in unison. And then we found a lantern, quite surrounded by snow. The lady took us round the lantern and back to the Lion. He had sprung out of the door and was in his full, kingly form, his mane shining in the snow and his great paws bringing him up right to our feet. I was afraid, but Emmie was the first to speak to him. He told us many things, and most importantly his name. He looked into her eyes and she grew to love him even though it was only moments ago that she had seen him. Then he looked into mine, and I also –”

He blinked fast to get rid of some dampness in his eye.

He continued. “I asked him if he would come back with us, because life would be a heap better if we could see him. And the Lion said, ‘I am in your world. But there I have another name.’

“I married Emmie. Then one day she was going to London on the train. And you know how trains don’t always go where you think they are going to go. Well, this train must have taken her to Narnia…and she must have been meant to stay. For I never had her back.” He paused for a long while. Then the light came back into his eyes. “And I suppose you’re one of the handful who still believe in Narnia.”

Gabi pressed his wrinkled hand and smiled. ”I’ve never been able to stop believing in it,” she said simply. Then she looked around. “But if this is Narnia, it still looks an awful lot like Oxford.”

“Little Jack” let out several peals of deep-seated chuckles. “It is Oxford. Jack’s world. This is the meadow of the college where he worked.”

“So through his eyes this is what it all looks like.” Gabi gazed out at the centaurs and the fauns and the gryphon.

Jack led the way to a river. Gabi clearly remembered the college having a bridge, in this exact spot. But while everything else was the same, there was no bridge here.

Out of the river there leaped a half dozen naiads in aegean-coloured dresses made of river droplets. The river gods jumped playfully in front and behind them, their faces glassy but bright.

“Ah…” Jack adjusted his hat, which had become increasingly angled. “One more note. You shall see some fellow passengers if you drop by the Eagle and Child pub. Even a Fellow of mine.” Jack sent her a wink.

“They have paper, pens, and…passion?” she laughed, remembering the heated discussions over the inked scraps of paper belonging to the six men on the train. The Inklings. Naturally.

“Yes – though that may be for another day and another adventure.”

Gabi breathed in the view. “All these hills, and meadows, and nooks, and crannies – I really can’t comprehend it all fully how it’s the same and different at the same moment.”

Jack looked out across the river and across the meadow. “The Fellow said it this way—just that all the hills and meadows and crannies were in one sense just the same as the real ones, yet at the same time they were somehow different—deeper, more wonderful, more like places in a story—in a story you have never heard, but very much want to know.”

“Yes.” Gabi looked out at the naiads leaping in the sunlight. “A story I very much want to know.”