First, I am really enjoying HBO’s adaptation of George R. R. Martin’s Game of Thrones. I was enjoying the books immensely until I realized I was forgetting so much between volumes that it just made more sense to wait until the entire series is finished to dive into them again. My “to be read” stacks are perilously high, and having to reread an entire series of not exactly concise tomes every time a new volume is released takes a lot of all-too-scarce reading time away from other books, any one of which might become a new and beloved favorite.

Overall, though, I’m a fan. I mention that because what follows might be perceived as throwing shade on Mr. Martin’s books, or on HBO’s adaptations, and I don’t mean it that way. This is, in fact, not a review at all. It’s just a series of thoughts that occurred to me about my own writing, specifically in my Widening Gyre series, as I was watching the most recent episode of A Game of Thrones on HBO.

Sure, Professor Tolkien’s and Mr. Martin’s books have a lot in common … on the surface. Also, both Professor Tolkien and Mr. Martin introduce heroes of smaller stature. I stole this image, too, by the way.

I often hear Mr. Martin called “The American Tolkien”. I can see why people say that. (Was Lev Grossman the first?) Both write (or wrote) extremely complex fantasy novels, both have very passionate fan bases (with a great deal of overlap), both have created British Isles-inspired worlds rich with invented history and languages and, well, both authors have the initials “R. R.” in their names. But honestly, I think the resemblance ends there. The similarities are superficial at best.

Mr. Martin’s books are grounded in well the rather unpleasant realities of a world at war. Mr. Martin has made no secret of the fact that his books are inspired by true history, most notably the War of the Roses. When his books are brutal, it’s because, well, history was brutal. In fact, Mr. Martin has criticized Professor Tolkien, pointing out that his wars aren’t like the wars of history (they certainly aren’t), and even pointing out that The Lord of the Rings never bothers to address Aragorn’s tax policy.

To be fair, I think Mr. Martin’s complaints have more to do with how Professor Tolkien has become a template for lesser writers than with any real issue with The Lord of the Rings, but I think the point is an interesting one. You see, Professor Tolkien and Mr. Martin are writing books in the same genre only to the extent that it makes it easier for bookstores to know where to shelve them. Mr. Martin writes grounded, historically-based fantasy that appeal largely (I think) because they are so grimly real. The famous shocks and twists come from the harsh brutality of a world at war. Even the famous Red Wedding is based on two different historical events. To a large (and often uncomfortable) degree, Mr. Martin is writing history, with a few ice zombies and dragons tossed in.

Professor Tolkien, on the other hand, is writing myth. In his book The Inklings, biographer Humphrey Carpenter recounts a significant and now famous conversation between Tolkien and then-atheist C.S. Lewis. The two were walking among the colleges in Oxford on a September evening in 1931. Lewis had never underestimated the power of myth. One of his earliest loves had been the Norse myth of Balder, the dying god. All the same, Lewis did not in any way believe in the myths that so thrilled him. As he told Tolkien, “myths are lies, and therefore worthless, even though (they are) breathed through silver.” “No,” Tolkien replied. “They are not lies.” Tolkien went on to explain that early man, the creators of the great myth cycles, saw the world very differently. To them “the whole of creation was myth-woven and elf-patterned.” Tolkien went on to argue that man is not ultimately a liar. He may pervert his ideas into lies, but he comes from God, and it is from God that he draws his ultimate ideas. Therefore, Tolkien argued, not only man’s abstract thoughts, but also his imaginative inventions, must in some way originate with God, and must in consequence reflect something of eternal truth.

When creating a myth, a storyteller is engaging in what Tolkien called mythopoeia (myth-oh-pay-uh). Through the act of peopling an imaginary world with bright heroes and terrible monsters, the storyteller is in a way reflecting God’s own act of creation. Human beings are, according to Tolkien, expressing fragments of eternal truth. Tolkien believed that the poet or storyteller is, then, a sub-creator “capturing in myth reflections of what God creates using real men and actual history.” A storyteller, Tolkien believed, is actually fulfilling Divine purpose, because the story always contains something of a deeper truth. Myth is filtered through the artist’s culture, experiences, and talents, but it is drawn from a deeper well.

By Tolkien’s argument, all myth is a response, a reaction to the force of creation occurring all around us. Granted, this calls for a slightly different definition of myth — and ignores the perhaps (probably) different intentions of the storytellers — which, of course, we can never know in any case. But a story can be myth, Tolkien would argue. Indeed, it could scarcely be anything else, because any act of creation is a reaction to the call of the Divine. Tolkien and the Inklings were responding to the same “shout” that the creators of myth have been responding to throughout the ages — the utter magnificence of a beautiful, dangerous, and impossible universe.

I bring that up because I can’t help thinking that anyone who reads The Lord of the Rings and comes away asking about Aragorn’s tax policy has completely missed the point. (Although again, I think Mr. Martin is actually ranting against the clichés that sprang up from Professor Tolkien’s imitators, rather than the books themselves. The Lord of the Rings was groundbreaking … but I certainly can’t blame Mr. Martin for wanting to break the template. In fact, I applaud him.)

The twin ideas of mythopoeia and eucatastrophe are at the heart of Professor Tolkien’s work. Indeed, the deeply mythic concept of eucatastrophe, a sudden turn of events at the end of a story which ensures that the hero does not meet some terrible, impending, and very plausible doom, is antithetical to the core of Mr. Martin’s work. Professor Tolkien formed the word eucatastrophe by affixing the Greek prefix eu, meaning good, to catastrophe, the word traditionally used in classically-inspired literary criticism to refer to the “unraveling” or conclusion of a drama’s plot. For Tolkien, the term had a thematic meaning that went beyond its literal etymological meaning. It was at the very core of Christianity and his love of myth and art. It was a part of his very DNA.

Eucatastrophe is the blessed conclusion we all crave; it’s something we long for deeply in the heart — a time when wounds are healed, the broken are mended, and rights are made wrong. That longing, I think, is key. In that sense, Mr. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and Professor Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings are polar opposites, matter and antimatter.

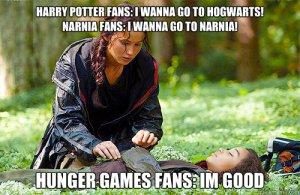

Let me ask you this. Would you really want to visit Westeros? There’s quite a few variations of this meme floating around on Facebook and Twitter:

There’s something in the mythopoeic works of Tolkien and Lewis that calls to that deep longing within us. There’s a part of us, somehow, that knows that the fantasy landscapes are a metaphor for something beyond, something more than the fields we know. It makes us feel almost homesick for a place we’ve never been.

I imagine that most of Mr. Martin’s fans can relate to the Hunger Games fans. A visit to the world of A Game of Thrones is … well, less appealing. This idea struck me when I was watching the most recent episode of HBO’s A Game of Thrones with my wife, Carol. The episode happened to feature two absolutely stunning shots of the castle Riverrun. Carol and I turned to each other with wide eyes and just said, “Wow.” The shots were lovely. It was, in fact, the first time I can remember that a location in A Game of Thrones had made us want to visit that place. The fact that there was a siege going on quickly damped our enthusiasm, but still, I was struck with the idea that A Game of Thrones is almost utterly devoid of any kind of wish fulfillment, key elements of fantasies like the Harry Potter series or, say, Star Wars.

It made me wonder if anyone would want to visit the locations in my books, or spend time with my characters. I hope so. I really do. At very least, I hope readers would long to visit the Renaissance festival in Blackthorne Faire, or the Commonwealth pub in The Widening Gyre. I try to ground things, solidly — a lesson I’ve learned from Mr. Martin — but mythopoeia and the longing for eucatastrophe are in my DNA, too.

Another thought struck me soon after. Both the television and the novel versions of A Game of Thrones are short on love. I don’t (necessarily) mean romantic love, but love. Love of family, love of place, love of friends, love of partner. When love is there, it’s usually broken in some way … think of the late King Robert’s lost love for Ned Stark’s sister, Lyanna. Think of Jamie and Ceresi Lannister (but not too much, because ewwww). Think of Tyrion’s love for his prostitute, Shae. Perhaps the purest love in the story is that of Ned Stark’s family, and look how that turned out.

By contrast, The Lord of the Rings is bursting with love, even though it is (almost) completely devoid of romantic love. There are certainly deep and loving friendships — Merry and Pippin for Frodo, Sam and Frodo, Gandalf and Bilbo, Gimli and Legolas. There is also a deep love of place … think of Frodo’s love for the Shire, all the walks he takes. Think how heartbreaking it is when Frodo’s ultimate sacrifice isn’t his life, but rather the life he has known and loved in the Shire. When he returns, his battles won, the Shire is lost to him, but not his love for it. Indeed, the whole story turns on the role of Providence, the divine love that leads to eucatastrophe, that dearest of all loves. The Narnia stories, too, are rich with love. So are the Harry Potter stories. They shine with love and grace.

Last — and this is something that the films missed for the most part — The Lord of the Rings, the novel, holds precious moments of comfort, even in the midst of terrible war and danger. There’s Bag End, of course (who wouldn’t want to visit Bag End?) — which, to be fair, the films absolutely nailed. But Bree, a port of (at least temporary) safety in the books, is a frightening place in the films. Ditto Lóthlorien, that precious place of unfallen paradise. Gone utterly are Tom Bombadil’s house and Crickhollow.

The dear and comfortable places make Professor Tolkien’s Middle-earth come to life. It makes us long to visit, just as (for example) Cair Paravel and Beaver’s Dam make us want to visit Narnia, and Hogwarts makes us long for an owl-delivered letter. For the most part, the Lord of the Rings films miss these moments of comfort, and the moments of the numinous. I think that’s why they’re less likely endure the test of time, as the books certainly have.

These moments are, at best, rare in A Song of Ice and Fire. Mr. Martin seems to be crafting more of a puzzle box, closer to, say, Lost than to The Lord of the Rings. When was the last time you heard someone talking about Lost? (To be fair, I expect a much stronger resolution to A Song of Ice and Fire.)

I wonder… when the last shock has shocked and the last twist has been revealed in all its gory glory, will we still turn to A Song of Ice and Fire? Probably. I certainly think so. I think Mr. Martin’s achievement is a remarkable one that will continue to find new readers for generations. I hope writers will learn the right lessons from it … break the templates, don’t just imitate the new ones.

I think A Song of Ice and Fire will gain as many new readers as The Lord of the Rings does. When all the mysteries are unfolded, and there’s no need to go back and scour the text for clues, I wonder if A Song of Ice and Fire will have as many re-readers? I don’t think so. I wonder, too, if A Song of Ice and Fire will inspire the same enduring love, and longing, that The Lord of the Rings kindles. Time will tell.

In the meantime, both have lessons to teach writers like me. I’ll ground my fantasies. I might even think about the tax policies of my own (metaphorical) Aragorns. But I’ll always season my stories with love, place, and comfort, even in the moments of darkness.

Mr. Martin isn’t the American Tolkien. He’s the American Martin. That’s more than good enough.