Over the past fifteen years, an immense number of books dealing with J.R.R. Tolkien have appeared on the bookshelves. No doubt Peter Jackson’s movies has provided some rather mighty advertising for the former Oxford don. Sadly, however, many recent authors who have written about Tolkien frequently fall into one of two camps: those who write about his Christianity, and those who do not.

Well, to be fair, every author mentions his Christianity. Almost no one, however, gets it quite right.

Even a cursory review of Amazon’s booklist reveals how many neo-Franklinites (those obsessed with scheduling and conforming their lives to the utilitarian rhythm of some eighteenth-century enlightenment god) and Christian evangelicals want to discuss the not-so-secret gospel message of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

On the other side, there are those who want to look only at Tolkien’s employment of paganism and his nearly divine faculty with languages. Many of the latter are divided, strangely, between atheists and fundamentalists. The atheists love his paganism while the fundamentalists despise it. Many of the fundamentalists, strangely, have no problem with the goddess Venus descending upon the good Christians of Lewis’s That Hideous Strength, but they fear Tolkien’s Sam’s prayers to Elbereth, queen of heaven.

Yes, it’s all so bizarre and so tangled, like much in this world of confusion–a world Tolkien both accepted and lamented.

What exactly were Tolkien’s views on the things that his followers seem so readily to divide over? Well, to be frank, they’re making divisions where no such divisions existed. First, Tolkien had as great a grasp of language as anyone of the past century. As one of his obituarists noted, Tolkien seems to have had the ability to get “inside language” itself. Not only could he write and speak some fifteen languages, he also designed several of his own. Scholars such as Carl Hostettler and Patrick Wynne have labored to preserve this aspect of Tolkien, publishing his dictionaries, grammars, and glossaries, as well as his translations, for example, of the Lord’s Prayer and the Hail Mary in Elvish.

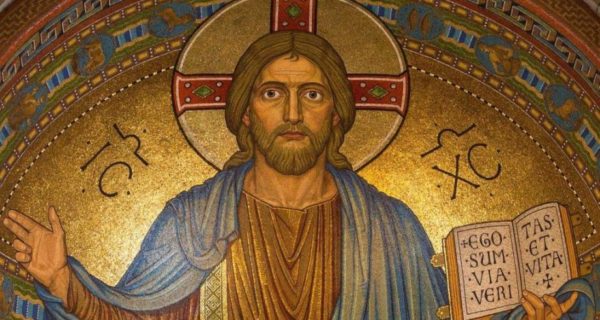

Second, Tolkien was a faithful Catholic, meaning he did not see Christianity as a break with the pre-Christian world, but as a fulfillment of it. That is, Catholics (and Eastern Orthodox) reject the misguided and inhumane (as well as strategically foolish) longing to erase all pagan elements of the past and begin anew. Instead, they understand that Christ came as a fulfillment—as much for the Jews as for the Greeks and the Romans and the Anglo-Saxons and Kenyans and Chinese and. . . you get the point. When early Christians encountered a pagan shrine, they did not burn it; they baptized it. Almost every Christian holy place in the Old World (and often in the New) sits atop a pre-Christian site of worship.

Gandalf serves as the perfect symbol of the many becoming one. As a member of the Istari, the Grey Pilgrim is equal parts St. Michael, Job, and Odin. He also holds one of the three offices of Christ: prophet. And yet, he is also fully Tolkienian.

And, third, Tolkien was indeed a loyal Catholic. Prior to Vatican II (which he accepted, but reluctantly), it would be difficult to find a single criticism of the Church from Tolkien’s pen or conversation. He had the Mass memorized in Latin, he carried his rosary with him at all times, and he attended Mass as often as possible. He and Christopher Dawson even attended the same parish. Catholicism was not just something that Tolkien participated in. He was fully Catholic.

As he saw it, his mother—a convert—had given her own life to pass on Catholicism to her children.

“My own dear mother was a martyr indeed,” Tolkien wrote, “and it is not everybody that God grants so easy a way to his great gift gifts as he did to Hilary [Tolkien’s younger brother] and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labour and trouble to ensure us keeping our faith.”

When Tolkien’s mother passed away in 1904, Father Francis Morgan, a priest in Cardinal Newman’s Oratory, raised Tolkien and his little brother.

When looking at Tolkien, a rather complex person, it is rather ridiculous and disingenuous to look him with the eyes and mind of an either/or construction. He didn’t love religion and only like language. And he didn’t love language and only like Catholicism. He wasn’t pagan, and he wasn’t anti-pagan. He was and loved all these things, and he saw no divide between a religion that preached the Word Incarnate and a scholarly life that focused on the use and deeper meaning of words.

A Word, a word.

No wonder Tolkien’s patron saint was St. John the Beloved and Revelator.

As proof of the coming together of these many things in Tolkien’s art and soul, one does not have to look any further than his Qenya Dictionary (Published as Parma Eldalamberon 12 in 1998) that begin with his learning of Gothic (the origin of all Germanic languages) and Finnish. Tolkien would take real languages and play with their possible developments and permutations, thus arriving at his invented languages. While it is impossible to date the exact origins of Qenya (Elvish), it’s clear it began sometime during in the year or two before his first year at Oxford and continued through his military service in World War I. In other words, this dictionary serves as the origins of his entire mythology that contains The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. And, from the very beginning, we can readily see how religious Tolkien’s understanding of language and mythology was.

The dictionary contains the following in Qenya: God the Father; God the Son; God the Holy Spirit; the Trinity; evangelist; nun; convent; and Crucifix.

And all of this before Tolkien had even conceived of a Hobbit.