I first read and finished The Lord of the Rings in the summer of 1977. I remember feeling like someone had kicked me in the stomach. I remember feeling a depression wash over me, not just because of the sad, somewhat dystopic ending, but because it was such a great book I didn’t want it to end. I had never encountered anything like it. I didn’t know at that moment that this was the beginning of a lifelong love of The Lord of the Rings and all of Tolkien’s works. I have reread The Lord of the Rings nearly annually since my first read more than forty years ago. Harry Potter came along a generation later and I was able to relive, to some extent, that same type of experience I had with The Lord of the Rings since it too was an exceptional piece of work.

Though very different books written in very different styles, they share many things in common. For me, they evoke an emotional response and a depth of feeling that transcend anything partisan lovers of either work who want to divide the world between Tolkien and Rowling have to say. I hold Tolkien and his work in higher esteem and affection, but that does not take away from my love and enjoyment of the Harry Potter series.

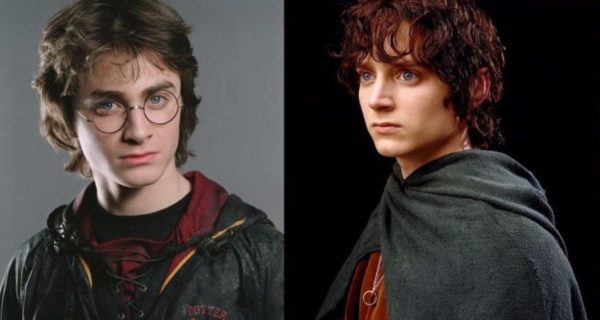

Each work has many heroes. The central hero in Harry Potter is Harry Potter himself, and he remains the primary hero from the beginning to the end of the story. Frodo begins as the central hero, but fades as the book goes on and others such as Sam and Aragorn increase in heroic prominence. Yet, Frodo is still the central hero in that he bears the largest burden and sacrifices himself more than any other. Frodo’s literary foil, the character whose qualities are in direct contrast to his, is not the Dark Lord Sauron. It is Gollum. Harry’s literary foil is Rowling’s version of the Dark Lord, that is Voldemort. All four of these characters have something in common other than being heroes or villains. They are all orphans and the love they receive or did not receive plays an interesting role or non-role in their character.

Frodo was orphaned at twelve when his parents drowned in a boating accident. Harry was orphaned as a fifteen-month-old when Voldemort murdered his parents. Voldemort was orphaned at birth, his father having abandoned his mother when he realized she had tricked him into loving her through a love potion. His mother went to an orphanage, gave birth to Voldemort there and died within the hour. Gollum too was an orphan, though this is not so obvious. We know in The Lord of the Rings Tolkien wrote about Gollum’s family being governed by his grandmother who eventually expels him from the family after he became corrupted by the Ring. I had read The Lord of the Rings many times and never thought much about Gollum’s parents or the possibility of him being an orphan. But in one of Tolkien’s letters, compiled in the Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien by Humphrey Carpenter, (Letter 214) Tolkien wrote about Gollum, “I imagine he was an orphan.”

Two of these orphans received love and two did not, yet they each responded differently. Frodo was lovingly adopted by his cousin Bilbo, whom he referred to as his uncle and was raised by him from the time he was twelve until he was thirty-three, which was when hobbits “come of age” and are considered adults. They had great love between them. There is no mention of Gollum’s parents, but he was clearly part of a larger family and there is nothing to suggest he was not loved by his grandmother until such time as his behavior became unmanageable.

Interestingly, Gollum and Frodo both began ownership of the Ring at age thirty-three. It is actually in their initial ownership that we see a striking difference of character. Frodo loved Bilbo and though he knew about the Ring while growing up, he clearly did not care about it. He delighted in his cousin/uncle and did not want him to leave. He was surprised Bilbo even left him the Ring. Sméagol referred to his cousin Déagol as “my love”, but clearly did not love him enough and murdered him when the latter withheld the Ring. Aristotle once wrote, “We become what we are as persons by the decisions that we ourselves make.”. Rowling had Dumbledore echo the same sentiment when he told the twelve-year-old Harry, “It’s our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.” In Frodo and Sméagol’s cases, it’s their choices that define both hobbits and show, despite these striking similarities, how different they are.

Harry was loved deeply by his parents who sacrificed their lives for him when he was a baby, but he was then raised by his abusive aunt and uncle. Voldemort simply was never loved and here we come to a point about the mystery of love and what truths these works of literature, these stories, reveal about love. Tolkien told his story mainly through words and actions of the characters, only occasionally letting you into their private thoughts, such as Sam’s internal debates when he believed Frodo had been killed by the great spider Shelob. We never get any thoughts or words from Frodo about his parents but we read and see his deep love for Bilbo and vice versa. But there is nothing to suggest his parents did not love him. Further, he had devoted cousins and friends in Merry, Pippin and Sam who loved him. So, we can pretty safely conclude he received great love in his formative years and beyond.

This is in contrast Harry’s upbringing. Harry certainly received love that he really couldn’t remember, since his parents died when he was only a little more than a year old, but we know that his mother’s sacrifice left a mark of love and protection on him. But he spent the next decade being essentially berated and mentally abused by his hostile aunt and uncle.

Frodo receives great love and demonstrates capacity for love. We see this in his nearly immediate reaction when he learns the truth about the Ring. His reaction is one of love as he decides to leave the Shire, his home that he loves, to protect it from evil by taking the Ring away from it so Sauron will not focus on it, but rather pursue him. Harry too repeatedly demonstrates his love for others by his courage and genuine desire to save others despite the danger it poses to himself. Hermione evens tells him later in The Order of the Phoenix that he has a “saving people thing.” In Frodo and Harry we have two characters, one who received love, and one who bears a stamp of love, but received nothing but abuse and neglect. With Frodo it makes sense that he was loving and sacrificial because that was modeled for him. For Harry, it was not modeled. What was modeled was quite the opposite. Dumbledore even marveled later in the story when he told Harry that is was amazing that Harry never lost his capacity to love despite the pain and suffering he endured.

We see a similar mystery in Christ’s love for His Disciples. For three years he trained and loved them. We know very little to nothing about their family backgrounds, but eleven of them responded to Christ’s sacrificial love and, in turn, grew in their faith and modeled the same sacrificial love. One, Judas, did not. Yet he had every opportunity to be like the rest. Christ tried to save him up until the end, offering him the bread and cup at the last supper, still seeking to redeem him. This is a point Tolkien mirrors with Frodo seeking Gollum’s redemption. Rowling mirrors this in her work, as well, when Harry tries to redeem Voldemort during their final confrontation. And here is the mystery. What was it about Judas that made him close off his heart and reject Christ? He had a character flaw when it came to money, according to the Gospel of John. Was that a brief glimpse into the man that points to why he closed his heart to Christ even after seeing and experiencing everything Christ did for three years to include miracles?

In his remorse, rooted in self-absorption like Cain, Judas kills himself rather than repenting and seeking Christ out for forgiveness. It is the same with Cain, in that we do not know why he allowed himself to be mastered by sin, yet Abel did not. Tolkien gives us a bit of the Cain and Abel flavor with Gollum and Frodo. Even before Sméagol, who becomes Gollum, finds the Ring and murders his cousin Déagol to keep it, we learn that his tendencies and character were not exemplary. Tolkien writes through the character of Gandalf, who recounts the story to Frodo of Gollum finding the Ring that “his head and his eyes were downward,” clearly letting us, the readers, know Sméagol is already going in the wrong direction. Tolkien also writes in letter number 214 that Déagol was a “mean little soul” and Sméagol was “meaner and greedier.” This is of course prior to them finding the Ring. There was something about Sméagol, something in him like Judas that caused him not to look upward, not to avail himself of the light so to speak, but to choose the dark. Something he couldn’t get past, or chose not to get past.

Voldemort, perhaps, is easy to explain. He never received loved and therefore never understood it, which is what led to his downfall. Dumbledore asks Harry, when showing Harry Voldemort’s pitiable past in the Pensieve, if now that he knows what he knows, did he feel sorry for Voldemort. Harry, due to his capacity for love, does. Voldemort seems like a classic sociopath in many ways, being devoid of feelings beyond those for himself and lacking a sense of basic morality. Yet, many people in real life have faced worse circumstances than the fictional Voldemort and have risen above it to be able to both receive and give love. What is Rowling trying to say – that the stamp of sacrificial love Harry received was enough to give him the capacity to retain his ability to love? That Voldemort received a stamp of abandonment and neglect, and was essentially discarded, and thus could not love? What is Tolkien trying to say with his characters and their intrinsic differences despite both receiving love?

I think the only safe conclusion to draw in exploring these fictional stories and fictional characters, as teachers of our reality when viewed through a Christian lens, is that it is indeed a mystery why some rise above their circumstance and some sink below them. Why some accept Christ and God’s love, while others reject them like Judas. It is a mystery of the human heart. We do see this truth, though, in both works: the truth of dying to self as Christ instructs, to gain our true selves and set us on the path to growth where we find our lives – the abundant life in Him that He promises – because we are willing to lose our lives, the lives we cling to on our own terms

Frodo and Harry were self-sacrificial, which led to their growth, and Voldemort and Gollum were self-absorbed, which led to their destruction. There’s something else about these stories and the two characters of Frodo and Harry that draw us to these stories as well. In their fictional lives, we somewhat see the stories of the saints we venerate. Frodo and Harry achieved a level of spiritual growth, though neither Tolkien, a devout Christian, and Rowling, a self-confessed struggling Christian – at least she seemed to be at one point and maybe still is – overtly address religion.

Early in the story, after Frodo has been through some trials but has many more ahead of him, Gandalf ruminates, speculating that Frodo will “become like a glass filled with clear light for eyes to see that can.” Frodo suffers greatly but grows in wisdom as the story evolves. He becomes a pacifist by the end, a person of peace, broken in body in many ways, and deeply wounded in spirit – the suffering servant who sacrifices himself utterly to defeat evil.

Harry too suffers and grows. He nearly dies and has a heavenly experience in a heavenly version of King’s Cross train station – the symbolism of this taking place in King’s Cross is unmistakable. While his body lies in a near death state, Voldemort, thinking he is dead, gleefully and mercilessly use the Cruciatis curse, the torture curse, to inflict more humiliation on Harry, but Harry can’t feel it even though he is aware Voldemort is doing it to him. He is immune to it now, having risen above Voldemort’s ability to harm him. In their final conflict, when Harry reveals himself alive and well to a shocked Voldemort, he even begs the Dark Lord to show remorse – trying to save him, much like Christ did with Judas. Voldemort, like Sauron who placed a substantial part of his being in the Ring so he could dominate others, had previously maimed his soul to preserve his life, placing piece of his soul in Horcruxes so could never die unless the Horcruxes were destroyed. Rowling reveals earlier in the story that the only possible way to repair your soul after indulging in such dark magic – which involved murder – was to begin with genuine remorse.

Frodo too tried to redeem Gollum. He showed Gollum genuine care, pitying him, and doing his best to be kind to him in hopes of reaching his heart. In what is among the most tragic moments in the story, Gollum is actually wavering, poised to genuinely repent, and reaches out to caress Frodo when Sam unwittingly wakes up, and thinking he is threatening Frodo, lashes out at him, causing Gollum to retreat back into himself. Tolkien describes it as a moment beyond recall. We see in Frodo’s saintliness a form of martyrdom. He is too broken and wounded at the end of the story to return to his life. He must leave the land he saved and go into the West, to the Blessed Realm where normally mortals could not go, to gain peace and find healing. Yet, most everyone around him is not broken but whole because of his efforts; Sam, Gandalf, Aragorn, Merry, Pippin, Legolas, Gimli, Éowyn, Éomer, Faramir and so on, essentially end up better off than they were. The story ends with the very sad and bitter sweet parting of Frodo from his beloved fellow hobbits.

Harry is not martyr, but like Frodo is a savior. He survives, not broken but whole. But unlike Frodo, there is much brokenness and death around him. The Weasley’s have lost their son Fred, and their other sons George and Bill suffer maiming wounds. Dumbledore Dobby, Lupin, Tonks, Sirius, little Colin Creevy and so many more were killed. Yet, the main impact of the stories channel through Frodo and Harry. Harry’s story ends in an epilogue with him reflecting how the scar, given to him when Voldemort tried to kill him as an infant, has not pained him in nineteen years and how, and I quote Rowling echoing Julian of Norwich, “All was well.”

Frodo and Harry are like James and John. Both Tolkien and Rowling hint at providence being a mover behind the scenes of the story. Tolkien pretty directly, Rowling less so. Christ chose both James and John as disciples. James died a martyr, John lived a long life and died at a very old age. So it is with all of the saints. Some are martyred, some live a long life, many of them suffer, but some do not.

I tend to reread The Lord of the Rings in the Fall and Winter, and Harry Potter in the Spring. I think it is a direct reflection of the ending of the stories. One reminds me of the lingering yet joyful sadness we all face in this life, reflected in the both the beauty of autumn even though things are dying, and the somberness and starkness and beauty of winter. And one reminds of me of the rebirth and joy that comes with spring. To me, The Lord of the Rings seems to go with the Nativity/Christmas season and Harry Potter with the Easter/Pascha season. When I do reread, reading Harry Potter in the Spring is always an antidote to the impact The Lord of the Rings makes on me. I identify with Frodo much more in my inner self, and Harry Potter with its happier ending, heals my inner Frodo. Maybe those of you who love these stories have similar reactions. We all know one day it will be our time to sail into the West, yet because of Christ we know all will be and is well.