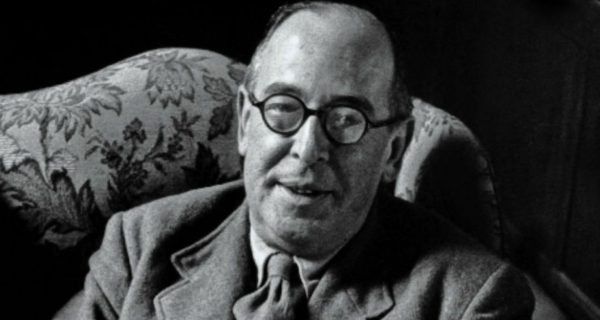

C.S. Lewis is one of the single most influential Christian writers in English and World Literature alike. Spanning from flights of whimsy to heady apologetics, his countless works include The Chronicles of Narnia, The Screwtape Letters, Surprised by Joy, and Mere Christianity. He is beloved not only for his warm sense of wit but also his expansive imagination and sense of the divine presence in his own life and all his creations. To him, God showed Himself through the Christological mystery that permeated such things as the natural world and the imaginal ones we sub-create with a numinous awe.

When I was in grade school, I was made to read two of the Narnia books in order to participate in a book review class. At the time, I was never much of a fantasy person, and I found the story decidedly out of my interest range. Hence, after I was finished with the cursory reading (and enduring the sock-puppet-special BBC production of the Chronicles!), I promptly moved on to bigger and brighter things than the newly released film epic The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. At the time, many of my friends and acquaintances were aghast that I refused to indulge in the new phenomenon, much less their old favorite The Lord of the Rings, and some even threatened, with all the best intentions, to tie me to a chair if I wouldn’t comply!

But it was not until I was 16 that I finally decided to watch the first Narnia films for myself. And believe it or not, it was the first film, and it’s compelling music score, that helped me come to terms with Lewis, and meet the heart and soul of the man who found Christ and sought to lead others to him through the means of good old-fashioned story telling. During the following years, however, his non-fiction works struck a particularly special chord with me, and I have been developing an ever deeper connection with and an appreciation for his works overall, in conjunction the works of his fellow British authors, J.R.R. Tolkien and Brian Jacques.

It seems that many Ringers have a habit of extolling Middle Earth at Narnia’s expense. “Well, it’s not Lord of the Rings”, is a common enough refrain whenever someone brings up something about Lewis’s brain-child. Not just Lewis, mind you, but also Jacques and his colorful and courageous world of Redwall and Mossflower Wood. But the simple fact is that Narnia and Redwall were never meant to be adult fantasies, and cannot be expected to display the same characteristics. And thank heavens they don’t. High-flying, big-budget adult fantasies are fine as they come, but sometimes we all want to relax and have some fun without getting swallowed up into the Dead Marshes.

Tolkien was a one-of-a-kind character who virtually dedicated his entire life to creating another world, with all the complexity of our own. But few can be honestly expected to repeat or mirror his accomplishment. He turned out a masterpiece, certainly, but there are many masterpieces with different styles, dimensions, and intents. They compliment one other, and form the tapestry that makes up a worthwhile anthology of stories that matter. Though it may be said that LotR has more depth and complexity than Narnia, the latter is an allegory for the Story of Salvation, and as such is armed to the teeth with powerful meaning. Of course, like Redwall, it is meant for a younger audience. But the truths taught are ageless.

What I have come to appreciate in all three authors, Lewis, Tolkien, and Jacques, is their penetrating understanding of the eternal battle of good and evil. The three of them had experiences in the World Wars of the 20th century, and the scars they had received never to have been far from mind. Their stories are hinged on the dual elements of paradox and grace. Refugee children, country hobbits, and peaceful monks, must rise above their simple backgrounds and battle against the powers of hell. They, it is emphasized, are in fact the only ones properly equipped to do so. Providence is with them to raise them up; it has been foretold that special grace will be given to them. It all comes back to the baby laid in a manger, and the carpenter nailed to a cross. Even in the blackest moments, there is the hope and belief that all things will yet be worked to good.

As I mentioned, it is in large part the music paired with the Narnia film adaptations that has especially brought Lewis to life for me. In the track “Evacuating London” from The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, I feel so strongly the workings of the author’s mind. There is pathos as the war separates a British family, just the sort of thing he probably encountered many times in the war years. Yet the music holds an undercurrent of a deeper meaning to suffering, the battle, the adventure that we must all embark on. There is Aslan just behind the door of an old wardrobe, if only we seek Him out. Also, in the score The Battle, when Peter Pevensie prepares to lead the armies of the Lion against the White Witch, the curtain of allegory seems to tear away, and the story of Easter comes blasting to the fore. There are times when the choral voices, although mostly inarticulate, seem to say “Jesu Christos”, and my mind’s eye sees Lewis gazing at me from across the years, saying “And that, my dear, is what it’s all about.” I don’t know anything with more depth than that.