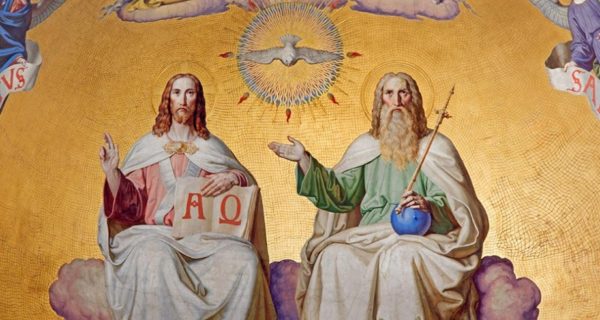

Trinity Sunday is often joked about in Christian circles as that day anyone can easily fall into heresy via poor analogies for an incomparable mystery. Some insist the topic should not even be broached unless one has a theology degree, and even then it’s a matter that treads thin ice. I, however, take for granted that analogies are inherently imperfect, not depicting what a thing is but rather highlighting certain aspects that are loosely comparable. They are useful in as much as they draw the faithful to meditate upon revealed mysteries and to expound upon them to others, and to humble us, in realizing that no matter how we ponder, we shall never know the full truth of it until the life to come.

In light of a bunch of interfaith conversations with Muslim friends regarding the Trinity and Incarnation, I think, perhaps, I have come to understand at least one of the root points of divergence, or perceived divergence, between Muslim and Christian understandings of the divine essence. It has to do with our different levels of comfort with revelation that transcends our ability to understand it, and as such our differing views of paradox as either antithetical to truth or a means of unveiling it. It also has to do with some misconceptions about what Christians actually believe when we speak about the Trinity.

When I hear a Muslim say that God has no partners, it doesn’t make me, as a Christian, automatically think it’s meant to disclaim the Trinity, because I don’t view the Trinity as some sort of committee board meeting of disparate parties. They can’t just take off in their own directions and fall to quarreling, like pagan gods are often depicted as doing. If anything, the Muslim objection is a foil to Christian heretical movements, but certainly not orthodox Christianity itself. When it comes to God for the Christian, They *are* He, and He *is* They. Confused? Good, that’s probably the right place to be, honestly. It proves we have finite human brains which cannot grasp divine mysteries.

If we were to make any pagan analogy at all, it would be the different “faces” of different deities, such as the Maiden, Mother, Crone of Celtic lore or Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva in Hindu mythology. But even that is exceedingly loose at best, and probably comparable to apples and pears. All the same, the Celts remained deeply connected to the mystical resonance of the number three, both in their paganism and their Christianity, and thus Celtic Christianity was and still is deeply Trinitarian in emphasis. The knot design symbolizing the triple goddess was converted into a token of “Father, Son, and Guide”, sometimes poetically depicted as “three hands” protecting a pilgrim through the journey of life. This is not dissimilar to St. Hildegard of Bingen’s description of “three wings”, one which is above (Father), the second below (Son), and the third which is everywhere (Holy Spirit).

But in keeping with our Abrahamic heritage, our understanding of the divine is not merely a super-powered being from another dimension of reality, as many pagan gods tend to be portrayed, but rather the essence of all realities, and indeed, unrealities (all that is seen and unseen, all that is and is not). All potential, whether realized or not, arises from God. Indeed, as Islam affirms in the Arabic tongue, la ilaha illallah. There is no god but God, or as the Sufis reflect upon it, there is no reality but the one reality. My belief in the Trinity does not in any way compromise my belief that God is, indeed, the only source and center of reality. If anything, it affirms it, in that I often believe I can see the Trinitarian mystery revealed in the world around me.

The human body, for example, has multiplicity within singularity in the various organs that keep it working, which in turn is played out in the “many parts” of the Church, which acts as the Body of Christ in this world. I see it when light shines through a multi-faceted prism, casting from a single crystal many colors. I can see it in the yolk, white, and shell of an egg, or the leaves on a clover. I can see it in the forms of water, ice, and mist. The triune aspects of mind, heart, and soul, or intellect, emotions, and will, further reveal this truth. There are three dimensions of reality found in length, breadth and depth, and three dimensions of time found in past, present, and future. God can be said to be Lover, Beloved, and Love itself, as well as the Knower, that which is Known, and the Knowledge itself.

Even in our subconscious archetypes, made manifest in tales told in almost every culture and century, there has always been something numinous about the number three…whether it be three kisses or three wishes or three tasks necessary for a hero to accomplish before the kingdom might be unleashed from a deadly curse. Always threeness finds completion in oneness, just as the family is a reflection this mystery, through masculine and feminine union bringing forth the new life of their children. Yes, all these things are symbols and signs, only as good as a metaphor can carry, and yet it intuits some greater truth beneath the surface that has always haunted us. All this lends credence to the metaphysical concept called “The Law of Three.”

As Chesterton wrote in his epic Ballad of the White Horse, capturing the mystery of the interaction between the human draw towards the internal workings of the divine: “The meanest man in grey fields one behind the set of sun, heareth between star and other star, through the door of the darkness fallen ajar, the council, eldest of things that are, the talk of the Three-in-One.”

When a Muslim says that God is indivisible, again, I wouldn’t automatically think that was intended to disclaim the Trinity, because I already believe the Trinity is indivisible, not pull-apart like a breakfast bun, or a patch-work quilt loosely stitched together. It is not God + a man + an angel/bird/what have you. God is the divine essential which binds the aspects into a full motion, like a spinning pin-wheel, where the prongs are made one in the singular swiftness of the motion. Each “person” is no less divine than the other “persons”, making the relationship distinct from them being parts of the pie that can be removed, thus reducing the quantity of God, since after all, God has no “quantity”, as we understand it.

They are equal in being and substance, but subordinate or superior only in role or position. The Father creates the world, and sends forth His Son to redeem it, and the Spirit proceeds from the love between the Father and the Son, which comes to rest within hearts opened to that indwelling. One analogy might be the fact that both yours truly and the Queen of England are equal in substance (our shared humanity) but differ in role (I’m a broke author, and she’s constitutional crown-toting corgi owner). However, unlike that example, there is oneness of essence that belies the separateness of individual mortals, and the outpouring quality of the Trinity is eternally co-existent. There has never been a time when the Son was not “begotten” of the Father, nor a time when the Spirit did not proceed from both.

Jewish mystical writings, such as the Kabbalah, emphasize that God is more a verb than a noun; a dynamic force, a whirlwind, a dance, and this, I think, is at the heart of the Trinitarian concept. God is motion, and interplay, and as such, from a Christian perspective, has never been “alone” even before time and space were created. Kabbalists would suggest this interplay takes the form of male and female aspects of the divine, the transcendent male Creator (“En Sof”) and the immanent female component through which all that is must flow (“Shekinah”). Christians would describe a similar concept in light of the Father (transcendent) and the Son (outpouring). As with any two distinct parts in dynamic, there must be, in some way a resolving force, the Love itself that kindles of the flame of the relationship. This, to us, would be the Holy Spirit. As such, God is one in essence and three in subsistence.

I often feel that poetic language fits the mystery better than sterile philosophical terms. There are many quotes from the saints that fulfill this mystical quality, and which I wish more non-Christians familiarized themselves with before broaching the discussion topic. It also helps to show the way in which the Trinity is spoken of in Christian devotional life, as a living, breathing force of faith.

For example, St. John of the Cross wrote: “The Blessed Trinity inhabits the soul by divinely illuminating its intellect with the wisdom of the Son, delighting its will in the Holy Spirit and absorbing it powerfully and mightily in the unfathomed embrace of the Father’s sweetness.”

St. Catherine of Sienna prayed: “O Eternal Trinity, my sweet Love, You Who are Light, give me light; You Who are Wisdom, give me wisdom; O supreme Fortitude, give me strength. O Eternal God, You are the calm ocean where souls dwell and are nourished, and where they find their rest in the union of love.”

St. Julian of Norwich reflected: “For the almighty truth of the Trinity is our Father, for he made us and he keeps us in him. And the deep wisdom of the Trinity is our Mother, in whom we are enclosed. And the high goodness of the Trinity is our Lord, and in him we are enclosed and he in us. We are enclosed in the Father, and we are enclosed in the Son, and we are enclosed in the Holy Spirit. And the Father is enclosed in us, the Son is enclosed in us, and the Holy Spirit is enclosed in us, almighty, all wisdom and goodness, one God, one Lord.”

St. Hildegard of Bingen again waxed mystical: “Therefore you see a bright light, which without any flaw of illusion, deficiency or description designates the Father; and in this light, the figure of a man the color of a sapphire, which without any flaw of obstinacy, envy or iniquity designates the Son, Who was begotten of the Father in Divinity before time began, and then within time was incarnate in the world in Humanity; which is all blazing with a gentle glowing fire, which fire without any flaw of aridity, mortality, or darkness is the Holy Spirit, by Whom the Only-Begotten of God was conceived in the flesh and born of the Virgin within time and poured the true light into the world.”

St. Elizabeth of the Trinity wrote in ecstasy: “O my Three, my all, my Beatitude, infinite Solitude, immensity in which I lose myself, I surrender myself to you as your prey. Bury yourself in me that I may bury myself in you until I depart to contemplate in your light the abyss of your greatness!”

None of this, as you can see, takes away from a grounding belief in God’s greatness, beyondness, and essential quality. Muslims excel upon the focus of these attributes of God, which are revealed in the 99 Names of Allah, and which are expounded upon at eloquent length in the Quran and various sermons and prayers from famous figures in the Islamic tradition, such as Ali ibn Abi Talib and his son, Hussain. Most of what they have to say I actually already believe in as a Christian; it’s what they reject or limit themselves from believing about God where we tend to part ways. This is because most Muslims perceive Christian belief, most especially those involving the outpouring and self-sacrificing aspects of the divine life itself, to contradict the greatness and omnipotence of God.

As I said earlier, perhaps this is simply because of my own comfort with Christian resolution paradox, with the mysterious both/and that has always been at the heart of our tradition. I’ve been asked if that bothers me at all, and can easily respond that it is this facet that actually makes me more in love with my faith. The Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Cross are the three things that attract me to Christianity most deeply, and they are the three things which most Muslims find most distasteful and mind-boggling. Indeed, I feel a special attraction to those saints who reflected upon and wrote about these mysteries most. Quite simply, I’m used to saying “yes” and “yes” to things that Islamic thought would interpret as being inherently incongruent and therefore categorically wrong.

Islam, as a religion based upon a recitation, typically has a more linear, orderly, mathematical style, which has a certain pragmatic emphasis. Christianity, on the other hand, has a more organic feel, like a wild hedgerow, and has a common function of holding together seeming contrasts and dichotomies with the belief that it actually reveals a new, often radical, truth which cannot be discerned through scientific weights, measures, or numerical equations. This “spiral effect” of Christianity, like the Trinity itself, has a way of going deeper and deeper down, plumbing the depths of things which on the surface cannot be dissected with tools of logic.

However, once that plunge is made, it opens up a sort of drop-down menu that expands on the common page of reference Muslims and Christians share. Once one sees the menu, and if it actually “click” something inside that makes it resonate, there’s no way of looking at the world the same again. That having been said, others who haven’t had the same “click” moment with the menu think the cheese has slipped off our collective Christian cracker. And trying to put myself in their place, and see the world through their particular set of goggles, I can understand that.

The question of whether these doctrines are simply inventions of men, or tools to serve a given end, comes up in conversation as well. I am obviously aware these issues were settled in Church councils made up of men; I also believe that God works through (you got it) men, in councils, bearing upon their shoulders the weight of the Holy Spirit, unfolding the destiny of the Church. I believe these doctrines were providentially inspired and intended to be formulated and finalized , not just as tools, but also as end to themselves, as a revelation of a dynamic within God (yes, just the Scriptures, the Word of God through the words of men). They are gifts to us I cannot dream of giving away.

They show us something about God’s nature that we, and the world, otherwise would lack. It is the revelation that makes us what we are, this Trinitarian Monotheism, upon which we bear and imprint in our souls through Baptism. That’s why the early Church hashed these topics out so fiercely, because this stuff was vitally important to our relationship with God and our standing with the world. As a result, the Christian understanding of who God is reveals a divinity that is integrally active rather than static, intrinsically relational rather than monolithic. God did not create us because He needed us for communion, but rather He did so out a superabundance of desire to share the communion already intrinsic to His Trinitarian nature. The divine reality is an overflowing chalice. It is this endless movement we see as making sense of the statement that “God *is* Love”, as opposed to “God *has* Love”, since dynamic must exist within God’s very essence and internal workings for such an attribute to exist.

The same is true of the nature of the Incarnation. For Christians, it’s this revelation we believe we have, an idea that is planted by seeds, passed onto us by word of mouth and pen, one that grows and develops and flourishes through the life of the Church. It is something we believe really and truly happened, something that makes itself manifest to us the more we open our eyes to its mysterious pull, something we can see hints of in the world around us, a point at which eternity infuses itself into a very specific time and place to undergo the tortures and triumphs of the human experience in solidarity with us, making all hardships grafted to the root of the cross.

This is why we might sing of the scandalous grace of One being crushed and defiled by sin and death, so that we might call Christ, the God-Man, our brother, and share a new life of grace by becoming part of His Body. Just as He rises from the dead, so we too are raised to new life. As St. Paul said in one of my favorite verses, “If any man be in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away. Behold, the new has come.” We might say this “new creation” shows a more important aspect of God than the old creation. One emphasizes power; the other emphasizes love. It is sort of an overflowing of the Trinitarian principle into our world, like a triple water-wheel of filling and emptying, ever-turning, simultaneously all-powerful and all-vulnerable, lover, beloved, and love all at the same time.

This is why in all things, Christians are called to mark themselves by making the sign of the cross over their bodies, in the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. It is one of the things that kept me religious even during dark nights of the soul; if I had been from another religion, say, Judaism or Islam, I believe I might have left. But Christ on the Cross would not let me go. It is this inheritance of the faith, one grounded upon the concept of the divine authority expiating itself and imbuing itself in the imperfect world of men. This view of heaven and earth being “wed” in Christ also enables me to see enlightenment, to greater or lesser extents, present in all the other religious traditions that have come into the being.

The wind of the Spirit I believe blows where it wills, and all peoples through history have been affected by it, relating to it through different levels and layers of Goodness, Truth, and Beauty. God knows what we do not, and I can easily believe the divine dance is more than capable of including those we deem “outsiders” within its cosmic rhythm. Perhaps, as the Archbishop of Canterbury once mentioned, Christianity and its worldview are more than just a gift for Christians, but rather a gift to the world which we share through thought, word, and deed based in the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity (still more Trinitarian connections there).

The fact is, this cycle or argument over the Trinity is likely to continue as it has for centuries, frustrating as it can be for Christians and Muslims alike. Most of us have the best of intentions trying to knock some sense into the other party, but casting a glance down through the trundle of history, we usually wound up just killing time at chronicled Crusade parleys, somewhere between taste-testing Mediterranean cuisine and watching the sultan’s belly dancers at the cross-cultural crash-bash. But on another note, perhaps God has actually been testing us all this time to learn to debate with grace, and make sure that in the process of discussing the divine we do not cease to see the divine presence in one another, which sadly has happened far too often.

If you believe in the Trinity and the Incarnation as I do, I would say one of the very worst things a person can do is to defile those beliefs by reducing them to sticks with which to hit people or undermine the sincerity of their own devotion to God. If you believe in the Trinity and Incarnation, then they should be transformative beliefs about God’s internal dynamic as Love itself, ever in motion in the divine dance, filling and emptying like a water wheel that never end, flowing out with such power that it incarnates in the dense, jagged reality of human existence, even to the chasm of death itself, so that divine life might be drawn even up from such depths.

To be Trinitarian, to be Incarnational, is to me to seek out the Lover, Beloved, and Love in everything, to see the image of God generously incarnating in this world through so many signs and wonders, simple and extraordinary. We should be able to see the workings of the Trinity not just in the things that strike us familiar, in Latin chants and vespers, in Renaissance painting and sculpture, in the crossing of ourselves at prayer, but also buried deep in the secret sanctity of the eyes of a friend from another land, in the kaleidoscope of geometric art that spells out order and sublimity.

It can be found in the rolling tongues foreign to our ears that sing of the tears of repentance to Ya Ilahi, in the poetry that could break one’s heart with its passion and poignancy, and beyond all this, in the complexity and confusion, and hurt and humility that should come with all attempts at bridging gaps, for we are all struggling, all stammering in our own ways, all on a journey, a caravan, all trying to remember who we are, where we’ve come from, and to Whom we shall return. As St. Augustine was reminded by the angelic boy on the sea, the mysteries of God are less likely to be understood in the here and now than the ocean can be emptied out by a sea shell.

If you believe in the Trinity, you should see it reflected everywhere, and if you believe in the Incarnation, you should see the face of Christ so strongly in your neighbor you would grant the kiss of peace to the stranger, the outcast, the “other”, even to your worst enemy in awe that you should be blessed with such an opportunity. After all, our souls are part of the divine dance too. We are all created in the image of God, but it’s up to us to reflect His likeness, which is inherently a call to communion, loving God with our whole heart, mind, and soul, and our neighbor as ourselves. Perhaps that is the beating heart of the mystery most deserving to be contemplated in our daily lives.