~By Michael Goth

Of the ten highest grossing movies of the eighties, two men were responsible for seven of them-George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Spielberg directed E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982), the film that surpassed Lucas’s Star Wars (1977) to become the highest grossing movie of all time. He also served as executive producer of Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future (1985). Having temporarily retired from directing, Lucas executive produced the popular Star Wars sequels: The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983). Spielberg directed and Lucas was the executive producer of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989).

“We’re making movie history,” George Lucas told British journalist Derek Taylor for his book The Making of Raiders of Lost Ark. Lucas was referring to the film’s epic scale, but Raiders of the Lost Ark made movie history in others ways: it became one of the highest grossing and beloved movies of all time, and launched a franchise that includes a prequel (Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom), two (with a third on the way) sequels (Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and 2008’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull) and a short lived television series, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992-1993).

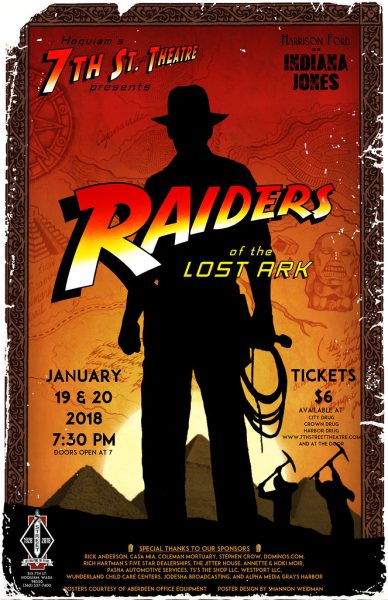

Raiders of the Lost Ark was released by Paramount Pictures on June 12, 1981. The film grossed $212,000,000 domestically, making it the fourth highest grossing movie of the decade. It brought in another $141,000,000 internationally. Harrison Ford starred as Indiana Jones, a suave professor of archeology and a swashbuckling adventurer. Karen Allen played Indiana Jones’s love interest, Marion Ravenwood. The supporting cast included Paul Freeman as French archeologist (and Indy’s chief nemesis) Renee Belloq, Ronald Lacey as Nazi Alfred Toht, John Ryhs-Davies as Indly’s friend Sallah and Denholm Elliot as Marcus Brody, the head of the archology department at the university where Indy teaches. Steven Spielberg directed, Lucas served as executive producer with Howard Kazanjian, and Frank Marshall was the producer. Lucas devised the story with Philip Kaufman (his initial choice as director) and Lawrence Kasdan wrote the screenplay.

“You sit back and say, ‘Why don’t they make this kind of movie anymore?’ And I’m in the position to do it,” Lucas told Taylor. Like Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark pays homage to the movie serials that Lucas and Spielberg grew up watching, which author Molly Haskell referred to in her book Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films as those “charmingly tacky adventure serials of the thirties and forties”. Lucas initially broached the subject to his friend Spielberg in 1977 while Lucas, his wife, Marica and Spielberg were vacationing in Maui as Lucas awaited the first week box office gross of Star Wars, a film he incorrectly thought was doomed to failure. Spielberg had wanted to direct a James Bond film, but MGM turned him down, and Lucas told him of an adventure serial that he thought even better than James Bond. Though Spielberg was intrigued, Lucas had already promised the film to writer/director Philip Kaufman. Kaufman dropped out of the project several years later and Lucas asked Spielberg to direct.

Though Lucas and Spielberg came to be associated with big budget action and special effects filled blockbusters, the two men entered the movie industry in very different ways.

While making Star Wars (aka Star Wars Episode IV-A New Hope) in 1976 and 1977, George Lucas had a near nervous breakdown that landed him in the hospital. As a result, he would not return to the director’s chair until the first Star Wars prequel, The Phantom Menace, 22 years later. Lucas would focus on producing, handing the director’s chair over to Irvin Kershner for Star Wars Episode V-The Empire Strikes Back (1980), to Richard Marquand for Star Wars Episode VI-Return of the Jedi (1983) and Steven Spielberg for the Indiana Jones movies. Lucas also executive produced Jim Henson’s fantasy classic Labyrinth (1986), the box office disaster Howard the Duck (also 1986), Francis Ford Coppola’s Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) and Ron Howard’s Willow (also 1988), to name just a few.

As a teenager in the early 1960’s, which he would depict in his 1973 hit American Graffiti, Lucas’s primary interest was not in filmmaking, but in race car driving and girls. On June 12, 1962-a few days before his high school graduation-Lucas was racing an Autobianchi Bianchina, when another car collided with him, flipping the car several times and tossing young George free of the vehicle before it crashed into a tree. He needed emergency medical treatment. After the accident, Lucas decided to pursue other career paths.

George Walton Lucas Jr. was born May 14, 1944, to George Walton Lucas Sr. and Dorothy Ellinore Lucas in Modesto, California. Young George had a love of comic books, rock n’ roll music and science fiction, especially the Flash Gordon serials on television. George was among a generation of filmmakers that included Spielberg, Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, called “The Movie Brats”, who were not part of the old Hollywood studio system and were often educated at film school.

As author Brian Jay Jones later wrote in his book George Lucas: A Life, when 18-year-old George left for college, he told his family that he would be a millionaire by the time he turned 30. At Modesto Junior College, Lucas studied anthropology, sociology and literature. While also at Modesto, Lucas became friends with John Plummer, a student who shared his love of European films. In a 2005 interview with Steve Silberman for Wired magazine, Lucas said that he and Plummer would attend regular screenings at Canyon Cinema of films by Jean-Luc Godard, Francios Truffaut and Federico Fellini.

Lucas transferred to University of California School of Cinema Arts, where he would become one of “The Dirty Dozen”, a group of maverick film students that included writers Hal Barwood and John Milius and future film editor Walter Murch, a frequent collaborator of Francis Ford Coppola. Lucas’s roommate was Randall Kleiser, later director of Grease (1978) and The Blue Lagoon (1980). Howard Kazanjian, a classmate at UIC who would later produce Raiders of the Lost Ark and Return of the Jedi with Lucas told author Garry Jenkins, in his book Empire Building: The Remarkable Real Life Story of Star Wars, that “George was a rebel.” Kazanjian recalled that his friend was “small, quiet, inquisitive, intelligent and witty.”

Lucas’s first professional film was THX 1138, a dystopian science fiction tale that he co-wrote with friend Walter Murch. The movie starred Robert Duvall and Donald Pleasence. Produced by American Zoetrope for $777,777, it was distributed by Warner Brothers, making a mere $2.4 million. The film received mixed reviews by critics. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times, wrote “THX 1138 suffers somewhat from it’s simple storyline, but as a work of visual imagination it’s special.” Vincent Canby of The New York Times also enjoyed the film. Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune was less kind, giving THX 1138 two out of four stars. The film would later gain a cult following, and in 2004, Lucas would release a director’s cut.

After THX 1138’s poor performance at the box office, Lucas’s friend Francis Ford Coppola suggested that George make a film that would appeal to a mainstream audience. American Graffiti was the result. Directed by Lucas, who co-wrote the screenplay with Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, the film is set in Lucas’s hometown of Modesto, California in 1962 and tells the story of rock n’ roll loving teenagers on their last day of summer vacation following high school graduation. The cast included many up-and-coming young actors including Ron Howard, Richard Dreyfuss, Charles Martin Smith, Cindy Williams MacKenzie Phillips and in a small role, 31-year-old Harrison Ford. American Graffiti was a huge hit both critically and commercially. It was the third highest grossing movie of 1973, just behind The Exorcist and The Sting and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. American Graffiti also created a sense of nostalgia for the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, which resulted in the sitcom Happy Days (starring Ron Howard) and the 1978 film Grease. To produce the film through Universal Studios, Lucas set up Lucasfilm, Ltd.

With a hit behind him, Lucas set out to develop a more ambitious film. The film Lucas had in mind was inspired by the Flash Gordon serials, the films of Akira Kuroswa, the Watergate scandal and Lucas’s reading into comparative religions. The film was called Star Wars (later retitled as Star Wars Episode IV-A New Hope). As Lucas saw the movie as more fairy tale than science fiction one, what he referred to as “a space opera”, he set the story A Long Time Ago in a Galaxy Far, Far Away… The film starred Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Peter Cushing, Anthony Daniels, Kenny Baker, Peter Mayhew and Alec Guinness. To create the film’s then groundbreaking special effects, Lucas formed Industrial Light & Magic. One can also not talk about Star Wars without mentioning John Williams’s classic score. Williams had been suggested to Lucas by Steven Spielberg, who had used the composer on The Sugarland Express (1973) and the blockbuster Jaws (1975).

Star Wars surpassed Jaws as the highest grossing movie of all time. It is a landmark of American cinema and became a pop culture phenomenon. Lucas had envisioned A New Hope as the first chapter in a three-part story, which was the middle section of a three-trilogy saga. As Star Wars continued to break box office records, Lucas began work on its sequel, The Empire Strikes Back (or Star Wars Episode V-The Empire Strikes Back). Deciding to produce and not direct, Lucas hired his friend Irvin Kershner (best known up until then for the 1978 thriller The Eyes of Laura Mars), to helm the film. Not enjoying the screenwriting process, Lucas devised the story and brought in Laurence Kasdan to write the screenplay. The cast of Star Wars returned and were joined by Billy Dee Williams. Once again Industrial Light & Magic created the special effects and John Williams scored the movie, composing perhaps the best music of his career. The Empire Strikes Back is a darker, more character driven story than its predecessor and introduced fan favorite character Yoda, a 900-year-old Jedi master. The Empire Strikes Back is a near perfect film and is regarded by many as the best of the Star Wars movies. Though it grossed only a quarter of what A New Hope had, The Empire Strikes Back was still a massive hit, the highest grossing film of 1980 and the 8th highest grossing of the decade.

The oldest of three children, Steven Allan Spielberg was born on December 18, 1946. “His mother Leah,” wrote Frank Sanello in his book, Spielberg: The Man, The Movies, The Mythology, “was an accomplished pianist. His father (Arnold) an inventor and electrical engineer who designed computers for RCA, GE and IBM. Spielberg and his work can be seen as a fusion of these two very different parents. His father’s influence contributed to the tech-no-wizardry which is the hallmark of most of Spielberg’s films, all those sci-fi epics and scare-’em-to-death roller coaster rides. His mother’s artistic bent provided the aesthetic balance which enriched his low-tech, character driven films like Schindler’s List and The Color Purple.” Steven was soon joined by three sisters: Ann, Susan and Nancy.

While growing up, the Spielberg family moved frequently, from Cincinnati to Haddonfield, New Jersey, to Scottsdale, Arizona, and finally to Saratoga, California. The Spielbergs were Orthodox Jews, something that Steven did not fully embrace until age 47 when he made his Academy Award winning docudrama Schindler’s List in 1993. Some in the industry even accused Spielberg of hiding his religious background. Don Simpson, the producer of Flashdance (1983), Beverly Hills Cop (1984) and Crimson Tide (1996) infamously said, “I’m surprised for a smart Jew, he’s as white bread as he is.”

Spielberg’s childhood was that of tract homes and middle class suburbia, which he would recreate in Close Encounter of the Third Kind (1977), Poltergeist and E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (both 1982). Poltergeist, the classic horror movie that Spielberg co-wrote and produced and was directed by Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Salem’s Lot), also depicted another part of Spielberg’s childhood: fear. A fear of a raggedy clown doll and a twisted and evil looking old tree right outside his bedroom window, both made their way into that movie. Spielberg told 20/20 in 1982 that as a young child he was even scared by Disney movies!

While living in Phoenix, Spielberg’s existing love of movies intensified. Films that he had especially enjoyed included Captains Courageous (1937), Pinocchio (1940), King of Monsters (1956) and, especially, Lawrence of Arabia (1962). With his father’s 8MM camera, young Steven directed about a dozen small films. While a student at Arcadia High School, he directed a 140 – minute science fiction, $600 budgeted film called Firelight, that would be the basis of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. After moving to Saratoga, Spielberg attended Saratoga High School for his senior year. A year later, Arnold and Leah divorced, with Steven moving to Las Angeles to live with his father, while his sisters stayed in Saratoga with Leah.

After the divorce, Steven had a complicated relationship with his father. This would be depicted in several of his films: a troubled marriage in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, an absentee father in E.T. The Extra -Terrestrial and a father and son who had barely spoken in 20 years in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Even Back to the Future, a film that Spielberg executive produced but was co-written and directed by Robert Zemeckis and co-written and produced by Bob Gale, begins with a McFly family where little love seems lost between George and Lorraine. Only the Freeling family in Poltergeist seem to have any stability. Though critics have pointed out that it is Diane Freeling and not Steve Freeling, who appears to be the head of the family.

Even though Steven Spielberg is the most successful of “the Movie Brats”, he did not attend film school or receive a former education in film.

In 1968, Spielberg directed a short film, Amblin’ (in 1981, Spielberg set up his own production company with producers Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy called Amblin Entertainment), a love story set against the backdrop of the late 60’s counterculture, that caught the attention of Sidney Shienberg, the vice president of Universal Studios. Spielberg dropped out of college and signed a seven-year contract with Universal. He was the youngest director to be assigned a long-term contract.

In 1969, at age 22, Spielberg directed his first professional film, the “Eyes” segment of the pilot episode of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery, starring Joan Crawford. At first the veteran actress was less than thrilled to be directed by a kid with no previous professional experience, but during filming she came to respect the young filmmaker. Spielberg’s work was well received by Shienberg, and he was given a full episode of Night Gallery to direct, a story called “Make Me Laugh”.

Over the next year, Spielberg would direct segments of The Psychiatrist, Owen Marshall, Marcus Welby, M.D. and the acclaimed Columbo episode “Murder by the Book” (written by a young screenwriter named Steven Bochco, who went on to co-create Hill Street Blues, L.A. Law and NYPD Blue) Spielberg was making a good living directing television, but what he really wanted to do was direct film.

Spielberg’s transition from episodic television to film started with the classic television movie Duel. Based on a short story by Richard Matheson (who also wrote the teleplay), Duel is the story of David Mann, a businessman on his way to a meeting, whose life is put in danger by a psychotic truck driver. Like much of his early work, Spielberg followed the example of Alfred Hitchcock by telling stories involving everyday people who become involved in extraordinary situations. It’s a foolproof formula as audiences will identify more with characters who they relate to. Writer Matheson believed this too, going as far as to give his character the last name Mann, as in everyman. Duel remains one of the greatest television movies ever produced. Universal released Duel theatrically in Europe.

Spielberg went on to direct two more made for television movies: Something Evil, a horror story starring Sandy Dennis and Darren McGavin; and Savage, an unsold pilot written and produced by Columbo creators Richard Levinson and William Link and starring Martin Landau and his then wife, Barbara Bain.

In 1974, Spielberg made his feature film debut with the underrated crime drama, The Sugarland Express starring Goldie Hawn, William Atherton and Ben Johnson. Though the film did poorly at the box office, it marked the start of a decades long association between Spielberg and composer John Williams. The film’s producers, Richard Zanuck and David Brown, were impressed with Spielberg’s work and approached him to direct the film adaptation of a bestselling novel by Peter Benchley. The novel was called Jaws.

The story of a great white shark terrorizing Amity Island and the three men who set out to stop it-police chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), marine biologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) and shark hunter Quint (Robert Shaw)- Jaws broke all previous box office records and surpassed The Exorcist as the highest grossing movie of all time. Jaws is often credited for creating the summer blockbuster, but it is also a well-made thriller and a classic of 1970’s cinema.

Spielberg followed Jaws with an even better film and one that was very personal. So personal was Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Spielberg-who has said himself that he is not a good writer- wrote the screenplay. He was reunited with Richard Dreyfuss, who played Roy Neary, an electrician who while out during a blackout witnesses several alien spacecraft in the sky. The cast included Melinda Dillion, Terri Garr and French director and occasional actor Francois Truffaut. The cinematography by Vilmos Zsigmond and visual effects by Douglas Trumbull (2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Trek: The Motion Picture) are a feast for the eyes and it’s backed by one of John Williams’s most beautiful scores. Close Encounters of the Third Kind is one of Steven Spielberg’s masterpieces.

After an underrated gem (The Sugarland Express) and back-to-back classics (Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind), 1979’s big budget comedy 1941 would be one of the biggest misfires of Steven Spielberg’s career. The film takes place after Japan’s attack on the navel base at Pearl Harbor, has an all-star cast that included Dan Ackroyd, John Belushi, Nancy Allen, Ned Beatty and John Candy, and a budget so high (a then astonishing $35 million) that Universal had to make a deal with Columbia Pictures to co-finance the film with them. Though 1941 did respectable business, it grossed nowhere near as much as Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, something it would have had to have done to make any real profit. The biggest problem with 1941 though is quite simple: it’s not a good movie. It’s a comedy, but seldomly is it funny.

Spielberg was set to produce a romantic comedy, Continental Divide starring John Belushi and Blair Brown, with Michael Apted (Coal Miner’s Daughter, The World is Not Enough) directing. The screenplay was the first by a young screenwriter named Lawrence Kasdan. Spielberg showed the script to Lucas, who was impressed enough to hire Kasdan to write the screenplay for Raiders of the Lost Ark. After a five-day brainstorming session between Lucas, Spielberg and Kasdan, the screenwriter wrote a first draft screenplay over the course of five months, drawing inspiration from movies like The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Great Escape (1963).

The success of Raiders of the Lost Ark would depend in no small part on who was cast as Indiana Jones. Spielberg and Lucas both thought that Harrison Ford would be the ideal Indy, but having worked with Ford on American Graffiti, Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back, Lucas felt it best to go with a different actor, preferably an unknown. As Brian Jay Jones wrote in George Lucas: A Life, “He was very impressed with Tom Selleck.” At age 35, Selleck had yet to really make it as an actor, having appeared mostly in small roles in television and film. However, in 1980, Selleck was cast as private investigator Thomas Magnum in the CBS series Magnum, P.I., making him unavailable for Raiders of the Lost Ark. After auditioning actors like Jeff Bridges, Christopher Reeve and David Hasselhoff, Lucas decided to go with Harrison Ford. One of the actresses that read for the role of Marion Ravenwood was Sean Young, who would star with Harrison Ford a year later in Ridley Scott’s science fiction masterpiece, Blade Runner.

Harrison Ford was born July 13, 1942, in Chicago. He graduated from Maine East High School in 1960. Like Tom Selleck, Ford’s acting career didn’t take off immediately. He found work on television in such popular shows as Ironside and Gunsmoke but worked as a carpenter (including building stages for the rock band, The Doors) to pay the bills. Ford was already 31 when Lucas cast him in American Graffiti. Francis Ford Coppola cast Ford in a small part as an F.B.I. agent in The Conversation (1974), but roles were still scarce. Then came Star Wars. Soon bigger roles followed in Force 10 From Navarone (1978) and the Frisco Kid (1979) and, of course, The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

Lucas shopped Raiders of the Lost Ark around Hollywood, with every studio turning the film down, believing that the movie would cost too much to produce, and that Spielberg would deliver another 1941. Despite the huge success of Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Spielberg was now seen around Hollywood as the man behind a big budget flop. Finally, Michael Eisner at Paramount agreed to finance the film, with the stipulation that Paramount would receive 60% of the film’s profit until it broke even then Paramount and Lucasfilm would divide the profits evenly.

Lucas’s brought in his friend and former University of California classmate Howard Kazanjian as an executive producer. Over the last decade, Kazanjian had served as an assistant director on Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) and Alfred Hitchcock’s final film, Family Plot (1976). Spielberg brought in Frank Marshall as producer. Marshall had worked with director Peter Bogdanovich on The Last Picture Show (1971), Paper Moon (1973) as well as Walter Hill’s cult classic, The Warriors (1979). Filming began on June 23, 1980.

Upon its release, Raiders of the Lost Ark was received with almost universal praise. The only criticisms were often regarding the film’s violent ending (this was before the PG-13 rating, so Raiders went out with a PG rating, essentially making it viewable to any age moviegoer) and its depiction of the Nazi’s as cartoon villains, something Spielberg would later regret.

Raiders of the Lost Ark is also a character journey for Indiana Jones. When we meet Indy in 1936 South America, he’s no more respectful of the artifacts he collects than his rival Bellog, something the French archeologist rightfully points out in the film. Initially George Lucas and Lawrence Kasdan saw Indy as a playboy, his archeology work not for the university museum’s benefit, but for the money it would put in his pocket so that he could carry on his lavish lifestyle. Howard Kazanjian fought for a more heroic Indy, but some the of the character’s flaws (not necessarily a bad thing) found their way into the movie. When Indy sets out to find the Ark he sees it as only a great archeological find, despite warnings from Marcus Brody and Sallah that the Ark represents a power greater than man. By the end of the story, Indy has developed respect for the powers of the Ark, which leaves him and Marion alive, while Belloq and Nazis are whipped off the face of the Earth by the wrath of God. This more mature Indy would carry through the later films. In Indian Jones and The Last Crusade, we would see some of Indy’s early respect for historical treasures when as a teenager, young Indy (River Phoenix), would attempt to retrieve the Cross of Coronado from thieves because, “It belongs in a museum”.

Works Cited:

Campbell Black, Raiders of the Lost Ark (novelization)

Molly Haskell, Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films

Brian Jay Jones, George Lucas: A Life

J.W. Rinzler, The Complete Making of Indiana Jones

Frank Sanello, Spielberg: The Man, The Movies, The Mythology

Darek Taylor, The Making of Raiders of the Lost Ark