When a party of Christians visited Prophet Muhammad (saw), in Madinah, he invited them, while they stayed, to sleep and say their prayers in the masjid. Sometime before, he had come to Madinah with the Muslims from Mecca as welcome guests and, upon being informed that the Jewish citizens were fasting, instructed his followers to also fast in communal solidarity. I take these undisputed events as clear indications of how Muslims should try to always behave humanely as strangers, hosts, guests, and neighbours.

The Qur’an goes even further when discussing how the polytheists of Mecca were to be treated in Chapter 109 “The Disbelievers” –

In the name of Allah the Merciful, the Beneficent

Say: O disbelievers!

I worship not that which ye worship;

Nor worship ye that which I worship.

And I shall not worship that which ye worship.

Nor will ye worship that which I worship.

Unto you your religion, and unto me my religion.

So, while we do not worship with or as you do, there is no command to interfere even with a disbeliever’s worship, let alone that of a Christian, and neither is it forbidden to share and enjoy communal holidays. It is very disappointing, to me, that, each year, as we approach Christmas, to hear the voices of those who wish to treat Christians and other Muslims worse than people of other faiths, no faith, or bad faith. Not that faith differences should ever be an excuse for rudeness, prejudice or injustice. Many of these negative preachers will take fragments from the Qur’an out of the textual and historical contexts to justify the divisions that they promote. However, the overwhelming influence upon their opinions was written by Islamic authors close to times of wars and invasions

A much larger work than this article would be needed to discuss the copious polemic writings of the important, but infamous, scholar ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328) in which he attacked almost all co-operation by Muslims with Christians, Jews, foreigners, and other Muslims, in defence of the vision of the perfect Islamic society he had constructed. In the UK, not long ago, there was a furore in the press when a student complained to them that he was required by his college to read a text by Al-Muhaqiq al-Hilli (1205-1277 CE) because he objected to its insulting comments about Christians and Jews. Muhaqiq is undoubtedly a pivotal scholar in the development of Islamic jurisprudence and his works are essential reading for students of law but, it should be considered, he was born one year after the Crusader sack of Constantinople, and 39 years before the end of Crusader ambitions in the Holy Land. In later life, he also lived through the Mongol invasions, which began in 1244, and included that led by Hulagu Khan that, in 1258, destroyed Baghdad and the Abbasid Caliphate. Invasions that ravaged the people, farms, and cities of the Fertile Crescent until 1323. Muhaqiq’s is a voice from a world that was burning. For him, the world outside the rule of Islam was peopled by monsters who looked like humans but were destroying peoples, trampling civilisation, and behaving with the heartless cruelty of beasts or demons. These experiences and reports of them scarred him with fear and revulsion which surfaced, from time to time, in his writing. While these comments by Muhaqiq make very unpleasant reading, they should be taken in context as important unwitting evidence of those times, and the effects war, fear, and horror may have had on even a rational mind and an outstanding intellect.

The majority of Christians that I know – although there may be one or two that differ, especially during wars – do not take their readings of the slaughter ascribed within the Bible to Joshua, Saul, and Herod as paradigms for dealing with their neighbours, nor do they ask their friends in faith to destroy those offensive pages. As with all texts, the reader must interpret the text and decide what is opinion, to be put aside, from what is meaningful for them to act upon. This is not a Christian or Muslim precept but simply the rational method and ethical principles which we share. Books, yours and ours, are preserved not just for their firm good guidance but also to record those deeds that, though perhaps forgiven, are surely best avoided.

It may seem strange that, when discussing Christmas, an apology for a Muslim scholar’s xenophobic excesses is included. However, what is thought and said of others are barriers found around all peoples, and Christmas is one of those times when strangers may easily pass through those obstacles to greet each other in the name of God, without being thought alien to each other or to the modern world. It is a time when Christians proclaim peace and peace is a call to which Muslims must respond. It is one of the times for armistice and reconciliation during which we may look closely at the causes of human errors and sins, rather than just fighting symptoms. The ability to recognise differences is both a natural and essential gift, but, when we allow laziness to reduce, in wilful ignorance, all men to groups whose actions’ we think we can predict, and whose thoughts we think we understand without listening, and considering, to what they say. Yet, when governed by indolence, this God given talent develops into the diseases with which we are all infected, of wrongful discrimination and unjust prejudice. I do not see the cry of ‘peace to all mankind’ as a call to idleness, but as an invitation to unite in the struggle with the demons within us that would destroy ideal humanity. It is an invitation that, in order to truly submit to my Muslim calling, must be accepted.

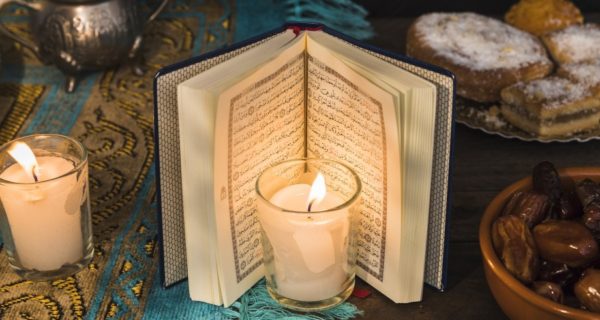

The Qur’an in Chapter 7, verses 31-33, is quite explicit that we should not deny ourselves the good things of life, should dress attractively for every type and time of worship, eat and drink of what is permitted, but not wastefully through excess. Naturally, there are things that Muslims may not do but these can often be easily explained. In the days after nine 09/11, I visited many churches wearing my turban and cloak; the full regalia. At one church, I declined a lady usher’s invitation for me to take Communion. “I can’t do that.” And I smiled in gratitude for her kind intention to share what she thought good. She came back a moment later, tapped me on the shoulder and said very earnestly “They won’t mind you’re not a Methodist.”

I have lost count of the times that someone has apologised for wishing me “Merry Christmas” or asked for permission to give me a greetings card. Let me be quite candid; I don’t care what is said to me if it is well intentioned, and, if you wish to give me greeting or present me with a festive book token, then do your worst because I will simply accept what is lawful for me, reply at least with courtesy, and forgive all the rest.

Yet, here we go again as those voices sound, condemning Christmas trees, roast dinners, presents given with love, and cursing those who give civilised responses to a neighbour’s seasonal greeting. Fortunately, most Muslims have good hearts and are not at war with every stranger, do not fester in ancient grudges, and rightly reject overly negative preaching, as well as attempts by assorted government authorities, in a misguided sense of equality, to remove Christianity from Christmas in case we Muslims are offended. If it might offend us, we would have let them know.

Although we offer special prayers, give in charity, feast, and give presents at every Eid, no sensible person refuses an extra holiday to mark the birth of someone holy that we love, respect, and pray for at every mention of his name. Most years, but perhaps not this, even though I am more interested in the season’s spiritual aspects, I roast Christmas dinner for my family and distribute (even more) presents, especially to the children so that they may more fully share the season with their classmates and friends. Opting out would be unfair since we share the country where we live and should enjoy with open hearts, sharing the opportunities for good our Lord Creator has provided, and preferably do so adorned with many smiles.

As with the stony Commandant in Mozart’s ‘Don Giovanni’, I must, before closing, insist that good manners demand of those giving the Christmas invitation to, in turn, accept my invitation to join with Muslims in the good deeds and, in healthier times, share the communal meals with which we celebrate the peace filled fasting month of Ramadhan.

I wish you all, friends, neighbours, and particularly those still strangers, with open hands and heart, what I wish for myself; a better life, a joyful Christmas, and a soberly repentant but, God willing, happily successful New Year.