It might surprise some to learn that one of the great works of twentieth-century war literature carries a pro-life message.

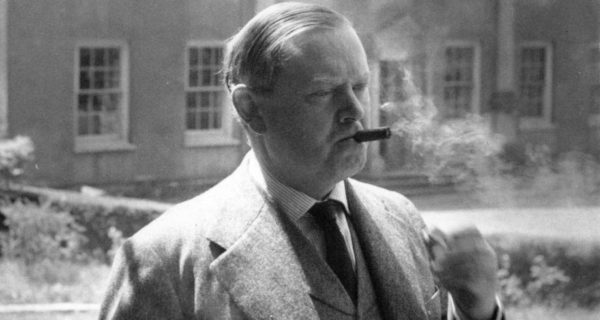

Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy (1952-61), set at the time of the Second World War, is a neglected work, no doubt, compared to the author’s most famous novel, Brideshead Revisited, but it might just be Waugh’s masterpiece.

At the root of this fine piece of literature is the matter of what a single life means in a world torn up by war, death and destruction. “Quantitative judgments don’t apply. If only one soul was saved, that is full compensation for any amount of loss of ‘face.’”

Contained within these words is a pro-life message that is at once cautionary and affirming.

Waugh’s central character in Sword of Honour is a Catholic Englishman named Guy Crouchback. At the start of the novel, in 1939, Guy is determined to make a difference – which, in 1939, means taking up arms against the two great evils of the day: Nazism and Communism. Praying to Sir Roger Waybrook, a crusader knight, at his tomb in Italy, Guy seeks a crusade of his own – forgetting, it seems, that Sir Roger died before he could ever reach Jerusalem. This is an omen.

Guy will still make a difference, but not in the way he assumes, not as a soldier, but as a father.

Like all great works of Catholic literature, Waugh’s novel is a subtle meditation on the relationship between divine grace and free will. A divine power works behind the scenes to set the main character on the right path.

The pivotal scene, I think, takes place in the third book, Unconditional Surrender, at the Requiem Mass for Guy’s saintly father, Gervase.

By this point in the trilogy, Guy’s soldierly aspirations and overall view of the conflict have not survived contact with the reality of the war. Having taken part in the debacle at Crete in 1941 – a real-life battle that was, for the British, a retreat followed by evacuation, which Waugh had taken part in himself as an intelligence officer – there has been little if any glory for Guy. What’s more, the Soviet Union is now an ally of Britain, collapsing his simplistic notion of an all-out crusade against manifest evil.

It seems that Guy has little left to fight for.

Then his father dies, but not before imparting to him the two key lines mentioned previously: “Quantitative judgments don’t apply. If only one soul was saved, that is full compensation for any amount of loss of ‘face.’”

What does this mean?

Well, at his father’s Requiem Mass, Guy ruminates on these very words as he, in his grief for both his father and the war, reconsiders his true purpose:

“One day he would get the chance to do some small service which only he could perform, for which he had been created. Even he must have his function in the divine plan. He did not expect a heroic destiny. Quantitative judgements do not apply. All that mattered was to recognize the chance when it was offered.”

His perhaps vainglorious desire for marital success was thwarted, but Guy prays for his deceased father’s intercession, still believing “that somewhere, somehow, something would be required of him”.

“Show me what to do”, he asks.

Guy has a wife, Virginia, though they are legally divorced. Despite marrying another man, Virginia falls on hard times and becomes pregnant by a no-good soldier named Trimmer. Here Waugh’s true story comes into focus. While visiting a doctor, Virginia hints that what she wants is an abortion. When the doctor refuses, Virginia tries an abortionist on Brook Street.

It is at this point that God intervenes on behalf of the unborn child, as well as the mother and ultimately Guy.

Arriving at Brook Street, Virginia finds that the abortionist’s house and the surrounding area has been flattened due to a German air raid.

Virginia does not give up just yet. Visiting another abortionist, a foreigner named Dr Akonanga, she discovers to her despair that he is unwilling to perform the termination – and Waugh adds the arresting line that Virginia was “haunted by the belief that in a world devoted to destruction and slaughter this one odious life was destined to survive”.

However, such “providence” leads to Guy’s opportunity to perform one small service, when, as a last resort, Virginia turns up at his door and informs him of her situation.

His summons has arrived.

In short, Guy marries Virginia for a second time to protect her and the unborn child. This noble deed, and the inevitable “loss of face” that results from it, is the culmination of Waugh’s trilogy.

One of Virginia’s friends dismisses his efforts and the notion of chivalry, but Guy replies:

“I don’t think I’ve ever in my life done a single, positively unselfish action. I certainly haven’t gone out of my way to find opportunities. Here was something most unwelcome, put into my hands; something which I believe the Americans describe as ‘beyond the call of duty’; not the normal behaviour of an officer and a gentleman; something they’ll laugh about.”

This choice echoes his father’s advice, “If only one soul was saved, that is full compensation for any amount of ‘loss of face.’”

This is a message that the pro-life movement must abide by continually if it is to achieve success in the long term. But what is implied in this message?

Firstly, it does not mean a curtailment of ambition. One soul, one life, is enough, but we can certainly aim for more. And there is, of course, the danger that, perceiving past losses and failing to appreciate our victories, however modest, we despair and give up.

Secondly, “the loss of face” in advocating for the unborn is not insignificant. Simply put, the desire to be thought well of by society can be overwhelming – and the return for such a “loss of face”, for many, is not worth the price.

This is why Waugh’s message is still relevant today.

The Catholic historian Christopher Dawson, writing in the 1950s, noted a “new form of persecution” that left “no room for the prestige of martyrdom”. Rather than being shot through with arrows and clubbed to death, like the celebrated Saint Sebastian, we moderns must suffer another kind of distressing fate – “a loss of face”.

In response to this, the perspective that Waugh’s trilogy forwards is that a “loss of face” is nothing compared to the saving of a soul, whether it be an unborn child, a mother or even oneself.

Take the case of Dr Leandro Rodriguez Lastra, for example, an Argentine gynecologist who was recently sentenced to a 14-month suspended jail term because he refused to abort a child at 23 weeks gestation – deeming that an abortion posed a risk to both the unborn child and the mother. Despite the cost, he saved at least one life and possibly two. We need such persons of character and principle.

Despite what Kerstie says to Guy – that “the world is full of unwanted children. Half the population of Europe are homeless… refugees and prisoners. What is one child more or less in all that misery?” – we must never forget the fundamental truth of the matter: that one child is everything.

If by speaking out and taking a stand for what is righteous and true, we save just one life, that is full compensation for any loss of face. That is the message of Waugh’s trilogy, that while making a difference might not necessarily win us accolades or glory, or even gain immediate victory in the short term, we must nevertheless be attentive to every opportunity to make even the smallest difference in defending the sanctity of life.