And they stripped him and put a scarlet robe upon him and, plaiting a crown of thorns, they put it on his head. (Matt 27:28)

Pilate said to them, “Here is the man.” (John 19:5)

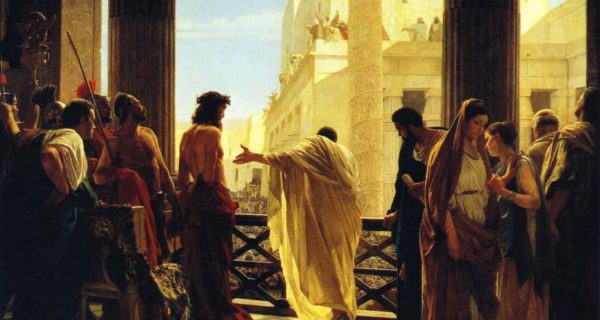

This is a staggering painting. In real life, it measures twelve and a half feet by nine and a half feet.

Remarkably, the scene is ‘framed’ from behind, a technique that places the viewer squarely within the canvas, inside the praetorium, as a complicit observer, just steps away from the centre stage. This significant reversal of perspective strews breath-taking light across the background of the painting, where the glare of the sun reflects off the colossal government building and picks out individual faces in the crowd as if they are, somehow, the protagonists.

Inside the cooler, darker chamber all but one of the characters’ faces are turned away from the observer; their inner thoughts veiled and left to the imagination. Strangely, the one illuminated and centrally-sited character is not actually the focus of the painting; he appears transparent and disembodied, his clothing merging with the edifice in the background.

A number of directional techniques within the painting compel us to look around, perpetuating the impression that we are really present: the position of the chequered floor tiles tells us that we are not face-on to the enormous throng; our eyes are quickly drawn from them to a distant point at the end of the crowded thoroughfare. The pillars take our gaze both upwards and outwards to the groups in each annex of the chamber – the praetorian guard to the left, representing the military power of Rome, and perhaps a cluster of lawyers to the right, one with a legal scroll in his hand, representing its judiciary.

The glances of the peripheral characters cause us to wonder what has caught their attention and we follow their stares; the guards scan the rooftops for signs of trouble while the lawyer appears to give a last look over his shoulder before departing. Maybe he knows his case holds no water. Finally, the gesticulating hand, as the point of convergence for the whole painting, re-centres our attention and introduces us to the man whom all the fuss is about.

In contrast to everyone else – except, perhaps, the woman by the pillar – he remains still and composed. Standing by the soldiers, his stature, his naked torso and the scarlet military robe reflect something of their own temporal masculinity and power. Yet his hands are tied and his head is bowed; it’s not clear whether his eyes are open. We know his story: he’s on trial for crimes for which the authorities can find no evidence; he’s been brutally flogged, humiliated and denounced, and the people are baying for his blood. But there is neither hopeless resignation in his bearing nor belligerence or resistance, simply acceptance and compliance.

Behold the man. Behold him. Hold-him-in-being. Hold him before you and ponder. Wonder at him.

Amongst all the surrounding opulence, power and moral high ground, what possible examples of manhood are we to take from his meek acquiescence?

Everything we’ve been taught about what it means to be a successful man, about achieving status, authority and riches is turned on its head by this otherworldly defendant: “If my kingship were of this world”, he says, “my servants would fight that I might not be handed over to the Jews; but my kingship is not from the world”.

Yet silhouetted against the bright, open sky, bearing the marks and crown of his mistreatment, his presence remains imposing.

Compare this to the governor in the centre of the scene, frantically occupying the crowds’ attention. Despite asserting his supremacy, (Do you not know that I have power to release you, and power to crucify you?), does he appear manly and authoritative? On the contrary, other than a foot, the back of his head and a gnarled hand, his spectral body is dressed in a translucent robe robbing him of substance.

Look at the vacated space around him. Note how distance has been placed between him and his throne, which he has abdicated in favour of pleasing the crowd. You would have no power over me, says the quiet man, unless it had been given you from above. The governor wavers, isolated and afraid.

Note too, the same distance placed between him and the woman standing tragically behind the pillar; his wife, whose desperate plea he has just ignored: Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much over him today in a dream. Her face, the only one wholly in view in the entire painting, carries the anguish of all abandoned and rejected women.

Two men – two models of manhood.

One, a classical representation of worldly supremacy though, in reality, a tyrant in the limelight, abandoning his duties as leader and husband and hanging on to his power in a moment of self-preservation by condemning an innocent man to death.

The other, a sacrificial lamb poised quietly in the wings, ready to fulfil a purpose in life that will literally bind him on a cross in duty to God and to the love of his spouse, above any temptations of worldly kingdoms or possessions.

Later, the epistolist will write, “Love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her”. This silent man will give himself up, totally, freely, consciously, decisively and with unwavering resilience, right to the agonising end. He does not open his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that is silent before its shearers, he does not open his mouth, wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities.

“For this I was born”, are the few words he says, “and for this I have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears my voice”.

From our vantage point on the stage of the praetorium we hear the governor’s question, “What is truth?”.

We can be grateful to Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI for taking up the reply, and to Pope St John Paul II for bringing this reflection to a conclusion:

God is truth itself, the sovereign and first truth. This formula brings us close to what Jesus means when he speaks of the truth, when he says that his purpose in coming into the world was to ‘bear witness to the truth’. Again and again in the world, truth and error, truth and untruth are almost inseparably mixed together. The truth in all its grandeur and purity does not appear. The world is ‘true’ to the extent that it reflects God: the creative logic, the eternal reason that brought it to birth. And it becomes more and more true the closer it draws to God. Man becomes true, he becomes himself, when he grows in God’s likeness. Then he attains to his proper nature. God is the reality that gives being and intelligibility. ‘Bearing witness to the truth’ means giving priority to God and to his will over the interests of the world and its powers (Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth).

So I invite you today to look to Christ. When you wonder about the mystery of yourself, look to Christ who gives you the meaning of life. When you wonder what it means to be a mature person, look to Christ who is the fullness of humanity. And when you wonder about your role in the future of the world, look to Christ. Only in Christ will you fulfil your potential. (John Paul II)