This year marks 80 years since The Screwtape Letters was published in book form (February 1942, to be exact). The book’s impact can be measured in many ways, such as how many writers have used its model. Os Guinness used it to critique modernism in The Gravedigger File. Randy Alcon used it to critique everything from education to modern art in The Lord Foulgrin Letters. Jim Peschke plays the concept from the angels’ side in The Michael Letters.

Sometimes though, one forgets that The Screwtape Letters isn’t just a great book about spiritual concerns, but also a great comedy. Written by an Irishman who spent most of his life in the United Kingdom, and published in an English newspaper at the height of World War II, it is particularly a British comedy. In fact, it fits into a particular British comedy tradition that Lewis didn’t realize would become massively popular.

What is this British Comedy Thing Anyway?

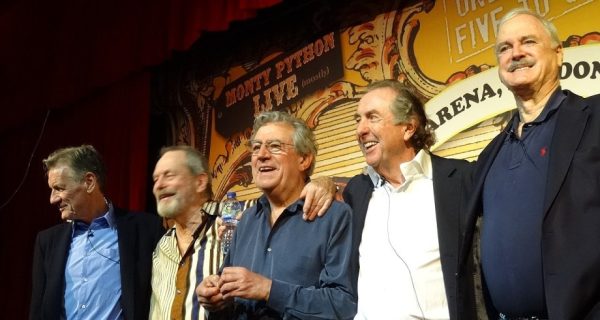

The question “what is British comedy?” is probably as old as the Britons. However, the question became more popular after Monty Python’s Flying Circus reached America in 1974 via a Dallas PBS station. The debate (on both sides of the Atlantic) about what separates British and American comedy has been extensively debated since the Pythons brought British comedy to a larger audience, with many sources giving many answers.

One helpful answer comes from Stephen Fry, who has extensive credentials. A Cambridge Footlights alumnus, Fry contributed to The Cellar Tapes, a comedy show that won the inaugural Perrier Award at the 1981 Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Later, Fry and his collaborator Hugh Laurie appeared in multiple seasons of the TV show Blackadder. Shortly after Blackadder ended, Fry and Laurie wrote and appeared in the acclaimed sketch comedy show A Bit of Fry and Laurie.

Speaking at the 2009 Hay Festival, Fry argued that the difference between British and American comedy is religion. American Protestantism emphasizes that “things are done by text and work, as opposed to by submission and doctrine,” thus downplaying human fallibility. British comedy owes more to European high church Christianity, which emphasizes original sin. Therefore, British comedy characters feel more conflicted, less secure. Fry describes the difference in this way:

“The American comic hero is a wisecracker who is above his material and who is above the idiots around him. All the great British comic figures are people who want life to be better, and on whom life craps from a terrible height, and whose sense of dignity is constantly compromised by the world letting them down. They want to wear a tie – they’re not quite smart enough to wear an old-school tie because they’re kind of lower middle class. They are Arthur Lowe [playing Captain Mainwaring] in Dad’s Army. They are Anthony Aloysius Hancock. They are Basil Fawlty. They are Del Boy. They are Blackadder. They’re not quite the upper echelons, and they’re trying to be decent and right and everything, trying to be proper. They’re even in David Brent from The Office. And their lack of dignity is embarrassing. They are a failure. They are an utter failure. They are brought up to expect empire, and respect, and decency, and being able to wear a blazer in public, and everyone around them just goes [Fry makes a raspberry sound].”

Frustrated Middle Men: A British Comedy Tradition

Several things stand out about Fry’s explanation. First, it mostly cites post-WWII comedy. Anthony Hancock began performing during World War II, with his persona Anthony Aloysius Hancock first appearing in the 1954 radio show Hancock’s Half Hour. The other characters (Captain Mainwaring from the TV show Dad’s Army, Del Boy from the TV show Only Fools and Horses, Basil Fawlty from the TV show Fawlty Towers, Edmund Blackadder from Blackadder, David Brent from the original UK TV show The Office) are all post-1967. This may explain why Fry says these characters struggle, for they were “brought up to expect Empire and respect.” The British Empire quickly lost much of its military stature after World War II, and suffered various cultural changes in the wake of the Profumo Affair and the Suez Crisis. (Peter Hitchens details the religious and cultural impact of these changes in his book Rage Against God).

Second, while some notable British comedians (such as Rik Mayall) don’t perfectly fit this profile, it sums up the post-WWII scene very well. Monty Python explored various conflicted characters in their TV show. The Pythons’ film Life of Brian follows an insufficient leader, Brian Cohen, discovering he’s been declared the Messiah against his wishes. Individual Pythons used insufficient heroes in their solo projects. John Cleese has provided the most popular iterations, particularly as the permanently aggravated hotel keeper Basil Fawlty in Fawlty Towers and as ineffectual lawyer Archie Leech in the 1988 film A Fish Called Wanda. However, other Pythons explored similar territory. Terry Gilliam’s first film as a solo director, Jabberwocky, follows a peasant who wants nothing more than to make money and marry a local girl, but is forced into becoming a knight and prince. Terry Jones’ final film, Absolutely Anything, follows writer Neil Clarke who hates his day job as a schoolteacher and finds life doesn’t get easier when he’s granted otherworldly powers. Each of these characters lacks confidence or drive, and routinely finds their attempts to improve life only complicate things further.

Outside the Pythons are various contemporaries and successors who have developed similar frustrated middle managers. Douglas Adams wrote Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which follows everyman Arthur Dent who wakes up to learn his home is being bulldozed… and his planet too. His friend Ford Prefect takes him into space to escape earth’s destruction, but Dent doesn’t like interstellar adventure one bit. Richard Curtis’ romantic comedies (including his lesser-known scripts for TV films Dead on Time and Bernard and the Genie) frequently follow an ineffectual young man too scared to take the initiative in everyday life or romance. Sometimes, as in Dead on Time, Curtis uses a plot device (“you have a fatal disease and will die in, oh, 30 minutes”) that increases his hero’s sense of helplessness. More recently, there have been British sitcoms like Peep Show, a story of two neurotic roommates who endlessly suffer from dilemmas they create. Co-creator Sam Bain called Peep Show a tale about “the stubborn persistence of human suffering” (Rensin 1).

Terry Pratchett explored this material extensively in his Discworld series and in Good Omens, the novel he co-wrote with Neil Gaiman. The Discworld novels have several recurring protagonists, the best-known being Rincewind, a wizard who can’t do magic and hates how he keeps landing in adventures where he’s supposed to help save the world. Good Omens presents Aziraphale, an angel who learns the devil’s son has been born, meaning the world will soon end. Aziraphale feels torn between following his divine orders and the fact he doesn’t want the world to be destroyed. He teams up with a demon who doesn’t care for Armageddon either, and they try to make the antichrist grow up to be a morally neutral boy who won’t serve good or evil.

Blackadder has an interesting place in this conversation. Each season followed a member of the Blackadder family (always named Edmund, always played by Rowan Atkinson) trying to make his fortune in a period of English history. In the first season, Edmund the Black Adder is the foolish son of Richard of Shrewsbury. His bumbling on a battlefield accidentally kills Richard III, setting up a fictional timeline where Richard of Shrewsbury becomes King Richard IV. Here, Blackadder seems a fool very much in the style of Arthur Dent. However, the next seasons feature Blackadders who are all clever men. This seems to suggest Blackadder evolves away from being the inadequate character that Fry described.

The fact is that even after Blackadder gains brains, he is still a frustrated man. Atkinson describes the post-season 1 Blackadder as “a cleverer man, [but] sort of stuck in the middle of a hierarchy” (“From Mr. Bean to Blackadder”). In Season 1, Blackadder is a king’s second (and totally unwanted) son. In later generations, Blackadder is a lord trying to impress Queen Elizabeth I (season 2), George IV’s butler (season 3), and a British Army captain on World War I’s Western Front (season 4). Each position gives Blackadder some power, but nothing he can really use, and no means to advance. Although he has more wit (“since the war started, our unit has progressed no further than an asthmatic ant with some heavy shopping”), his clever words all stem from anger. He desperately wants to be rid of his foolish companions, to achieve something higher, and takes out his frustration by being acerbic.

Furthermore, the plots routinely show that Blackadder truly isn’t qualified to be the hero and leader he wants to be. He almost never does anything heroic to show he’s worthy of something higher. Whenever he gets a chance to do something brave, he usually flees with a clever escape line. Ultimately, Blackadder is just as cowardly as Rincewind and suffers the same crushing disappointment as Arthur Dent. He is inadequate and frustrated, but he puts up a better façade.

Screwtape, Hell’s Mid-Level Office Manager

The “frustrated middle manager” archetype also fits Screwtape, although it may not be the book’s primary comedy vehicle. Many have highlighted how Lewis’ book allows him to lampoon human behavior. Many have noted Lewis’ humorous inversions (Satan becomes “Our Father Below,” God becomes “the Enemy,” and so forth). Underneath these layers of clever satire is another form of comedy. Lewis depicts Screwtape much like the condemned ghosts in The Great Divorce: comic in his all-consuming selfishness.

While Screwtape boasts his record of bringing many patients into “our Father’s house” (6) and his position as “the under-secretary of a department” (21), he’s not as brave as he seems. In letter 19, Screwtape backtracks his comment that God truly loves humans, and adds that his rude comments about Slobgub “were purely jocular” (111).

In the rest of letter 19, Screwtape goes out of his way to assert his allegiance to Hell, only sounding ridiculous. He asserts he was wrong to say God is love; such claims cannot be true.

“If only we could find out what he is really up to! … We must never lose hope; more and more complicated theories, fuller and fuller collections of data, richer rewards for researchers who make progress, more and more terrible punishments for those who fail – all this, pursued and accelerated to the very end of time, cannot, surely, fail to succeed.”

– The Screwtape Letters, 113

It’s easy to read these lines as the kind of character John Cleese might play. In fact, he did play Screwtape when he narrated Lewis’ book in 1988. An AudioFile magazine reviewer described Cleese’s Grammy-nominated Screwtape as “a bourgeois stuffed shirt – pedantic, punctilious, dry – as distinctly English as Mephistopheles is German” (“The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis read by John Cleese”).

As Screwtape’s relationship with Wormwood deteriorates, he becomes acerbic, like Blackadder putting down his underling Baldrick. Screwtape doesn’t resort to Blackadder-style insults (comparing his underling to a dungball or filthy animal), but he slowly sheds all pretense of affection. In letter 22, he informs Wormwood that his attempts to get Screwtape in trouble with Hell’s Secret Police have failed and gifts a pamphlet on “the new House of Correction for Incompetent Tempters” (129). In the final letter, after Wormwood loses his first patient, Screwtape stops pretending to care about his nephew: “Love you? Why, yes. As dainty a morsel as ever I grew fat on… Your increasingly and ravenously affectionate uncle, Screwtape” (188).

In short, Screwtape is a mercenary, and a frightened one. He acts confident until he wonders if he’s crossed a line others will punish him for. In fact, he’s not even in control of his own body, as seen in letter 22 when a “periodic phenomenon” turns him into a centipede (133). Screwtape may have some power, but he is severely limited and always fears being pulled back down. There is also the inconvenient fact that Hell’s top management position is permanently occupied: Screwtape can never reach the top. He is a frustrated middle manager stuck in an endlessly frustrating situation that achieves comedic proportions.

How Humorous is Screwtape?

However, Lewis would argue that Screwtape’s insecurity doesn’t make him humorous. In his preface to The Screwtape Letters’ 1961 edition, Lewis wrote that he avoided making Screwtape like Goethe’s Mephistopheles. Mephistopheles is “humorous, civilized, sensible, adaptable… [and thus] has helped to strengthen the illusion that evil is liberating” (xxxv).

Lewis argues that demons should not be humorous, for “humor involves a sense of proportion and a power of seeing yourself from the outside. Whatever we attribute to beings who sinned through pride, we must not attribute this… we must picture Hell as a state where everyone is perpetually concerned about his own dignity and advancement, where everyone has a grievance, and where everyone lives the deadly serious passions of envy, self-importance and resentment” (xxxv, xxxvii).

Lewis’ words about comedy establish two things. First, if a character has a sense of proportion, that means they have humor. Fry would argue that this defines American comedy characters—they are confident and full of one-liners (“Stephen Fry: America”). However, for a character like Blackadder or Screwtape, the humor may lie in the audience (who has the necessary sense of proportion to see the joke).

Second, Lewis’ description of Hell as a place filled with people eternally worried about their dignity and advancement sums up his characters in The Great Divorce pretty well. It also sums up all the aforementioned British comedies pretty well—or at least, what would those comedies would be like without side characters who balance the madness and give a sense of proportion. Lewis’ vision of Hell is Fawlty Towers where everyone is Basil Fawlty.

Thus, although Lewis forces readers to develop a nuanced understanding of comedy, his explanation doesn’t mean Screwtape isn’t funny. It means that Screwtape is funny without having humor himself. His explanation also proves that Lewis understood very well the character traits that came to typify British comedy.

Screwtape as Model and Theological Explanation for British Comedy

As noted above, Screwtape predates most of British comedy’s well-known “frustrated middle manager” characters. Anthony Aloysius Hancock can be seen as a contemporary character. The others mentioned in this essay appeared after Lewis’ 1963 death. Given that John Cleese narrated The Screwtape Letters, and Good Omens co-writer Neil Gaiman read The Screwtape Letters in school (Views from the Cheap Seats 34), one could argue Screwtape influenced this wave of “frustrated middle manager” characters.

Equally interesting is that The Screwtape Letters showcase what Fry claims fuels this character: a religious sense of fallibility. Screwtape doesn’t see his behavior in religious terms, but his comedic foibles derive from his metaphysical condition. He behaves foolishly because he lacks the knowledge he needs to grow. In letter 19, Screwtape says members of God’s faction have theorized “that if we ever came to understand what He means by love, the war would be over and we should re-enter Heaven” (113).

Screwtape cannot grow because he won’t see God’s truth and submit to God’s doctrine. The Fellowship for the Performing Arts stage adaptation of The Screwtape Letters, adapted by Jeffrey Fiske and Max McLean, captures this dilemma in a clever visual way. Most of the action occurs in Screwtape’s office, which has a vertical pipe for sending letters and a crooked stepladder. As an anonymous audience member observed during a Q&A after an April 2013 performance, the stepladder is so crooked that Screwtape cannot climb it… even in a final scene where he tries to see a commotion above (“The Screwtape Letters”). Screwtape cannot ascend.

Thus, The Screwtape Letters demonstrates Fry’s idea that British comedy is derived from Christian ideas about sin and holiness. Lewis tells a story about a non-humorous character in a darkly humorous situation: he will not let himself leave Hell. In The Great Divorce, Lewis plays conflicted, sinful characters from the opposite angle and shows them achieving freedom.

Interestingly, most of the British comedy characters mentioned don’t reach dark tragedy or full redemption. Some have darkly comic ends. About half the time, Blackadder seasons end with Blackadder dying. Occasionally he gets what he wants in the final episode, but it comes across more like a gag than something fitting his character.

Other stories go for glib nihilism. Life of Brian ends with the character on a cross, but then the crucified men sing, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.” Peep Show ended with the two irredeemable roommates back where they started. The first phase of Adam’s original radio program Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy ends with Arthur Dent and his friend Ford Prefect strolling through a prehistoric earth landscape. Their adventures have brought them to earth’s past. They know how it will be destroyed. They also find they can’t do anything to stop it. “What a life for a young planet to look forward to,” Arthur Dent mutters (Perkins 126).

Other writers aim for limited redemption or resolution. Blackadder acts bravely once, in the final season 4 episode where he and his friends die charging across the trenches. Still, The episode doesn’t feature Blackadder behaving nobler than in the other episodes. The trench charge is not a statement about him becoming heroic, but a larger statement about WWI soldiers’ deaths. Rincewind never grows in his Discworld adventures, but Pratchett’s novels often end with other characters growing. Good Omens ends with the devil’s son Adam stopping the apocalypse and remaking reality so he can still live as a regular boy. Adam avoids theological problems by embracing eternal innocence, a future involving “a boy and a dog and his friends. And a summer that never ends” (369).

Richard Curtis’ early romantic comedies set up the perfect girl as savior, so the hero needn’t grow. In Dead on Time, the man who thinks he’ll die in 30 minutes finds the girl he’s infatuated with. She understands everything he tells her (his death in under 30 minutes, his bizarre adventures to find her) and gives him a kiss before contacting his doctor to double-check his diagnosis. Curtis’ famous screenplay for Four Weddings and a Funeral features another perfect girl, who crosses the hero’s path several times but never stays with him. In the end, after the hero splits up with his fiancée during his wedding ceremony… the girl he’s always wanted shows up on his doorstep in the rain for him to claim. The man doesn’t grow, but the right girl fixes everything.

All these characters are entertaining, and the stories have great scenes. From a theological angle, though, they tend to falter at the end because few do what Lewis did so well: staring the hero’s spiritual dilemma in the face.

Will There Be More “Utter Failures” in the Future?

Looking back at 80 years of Screwtape, it’s interesting to think Lewis created a character who summed up a famous form of British comedy and did so years before Dad’s Army, Monty Python, and others made it iconic. Screwtape shows how a character can be an utter failure, have no humor, yet do highly humorous things. Screwtape’s dilemma shows how this kind of British comedy has a theological dimension, one its practitioners often miss. As time goes on, it will be interesting to see how British comedians keep wrestling with these ideas. Some (such as the upcoming second season of Amazon’s Good Omens TV show, picking up where the novel left off) may reach into the religious imagery that Lewis used so well and produce something interesting.

Sources Cited

A Bit of Fry and Laurie. Created by Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie. BBC, 1989-1995.

Absolutely Anything. Directed by Terry Jones. Lionsgate, 2015.

A Fish Called Wanda. Directed by Charles Crighton. MGM, 1988.

Bernard and the Genie. Directed by Paul Weiland. BBC, 1991.

Blackadder. Created by Richard Curtis and Rowan Atkinson. BBC, 1983-1989.

Dad’s Army. Created by Jimmy Perry. BBC, 1968-1977.

Dead on Time. Directed by Lyndall Hobb. Michael White Productions, 1983.

Four Weddings and a Funeral. Directed by Mike Newell. Rank Film Distributors, 1995.

Fawlty Towers. Created by John Cleese and Connie Booth. BBC, 1975-1979.

“From Mr. Bean to Blackadder, Rowan Atkinson Breaks Down His Most Iconic Characters.” GQ, June 24, 2022. youtube.com/watch?v=wq2T1h6tgDY.

Gaiman, Neil, and Terry Pratchett. Good Omens. Harper, World Books Night U.S. Edition, 2013.

Gaiman, Neil. Views from the Cheap Seats: Selected Nonfiction. William Morrow, 2016.

Hancock’s Half Hour. Written by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson. BBC, 1954-1961.

Hitchens, Peter. Rage Against God: How Atheism Led Me to Faith. Zondervan, 2010.

Jabberwocky. Directed by Terry Gilliam. Columbia-Warner Distributors, 1977.

Lewis, C.S. and Paul McCusker. The Screwtape Letters: Annotated Edition. HarperCollins, 2013.

Lewis, C.S. The Great Divorce. Geoffrey Bles, 1945.

Life of Brian. Directed by Terry Jones. HandMade Films, 1979.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Created by Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, Michael Palin, and Terry Gilliam. BBC, 1969-1974.

Not Stated. “The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis read by John Cleese.” AudioFile, July 1999. Accessed January 19, 2020. audiofilemagazine.com/reviews/read/5835/the-screwtape-letters-by-cs-lewis-read-by-john-cleese/.

The Office. Created by Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant. BBC, 2001-2003.

Only Fools and Horses. Created by John Sullivan. BBC, 1981-2003.

Peep Show. Created by Andrew O’Connor, Jesse Armstrong, and Sam Bain. Channel 4, 2003-2015.

Perkins, Geoffrey (ed.) and Douglas Adams. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts. Pan MacMillan, 2003.

Rensin, Emmett. “The British comedy Peep Show was a very funny show about very sharp pain.” Vox, December 23, 2015. Accessed January 19, 2020. vox.com/2015/12/23/10650876/peep-show-series-finale.

“The Screwtape Letters.” Adapted by Jeffrey Fiske and Max McLean, directed by Max McLean, performance by Brent Harris and Tamala Bakkensen, Fellowship for the Performing Arts, April 27, 2013, Pikes Peak Center, Colorado Springs, CO.

“Stephen Fry: America.” Hay Festival, May 25, 2009. hayfestival.com/p-1092-stephen-fry.aspx.

1 thought on “Did Screwtape Predict Monty Python?: C.S. Lewis as a Contributor to British Comedy”