An ongoing debate in sci-fi and fantasy literature is how it handles “Might as Right,” the way heroes use force to get what they want.

The Inklings’ contemporary T.H. White made this debate central to his Arthurian epic The Once and Future King. White’s King Arthur is a warrior striving to redirect his knights’ views about using force, their tendency to see war as a game, into something new: a system of chivalry that will hopefully remove force eventually.

While Lewis and Tolkien don’t lean as far into pacifism as White does, their stories (informed by their experience as World War I veterans) carefully avoid portraying war as inherently fun or glorious.1 Lewis routinely depicts war as necessary but ugly in his Narnia stories. Wars happen, as in the fight with the White Witch’s forces in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe and the Arkenlanders fighting the Calormenes in The Horse and His Boy.

However, Lewis usually eschews big battle imagery and focuses on something small within the battle scene: Edmund’s wounds or Shasta nearly getting killed. Rather than making war seem hypnotic or glorious, Lewis focuses on who has been hurt: the fight was necessary but not glorious.

Tolkien also presents a cautious view of war. Miriam Davidson highlights the “nonviolent countercurrents” in The Lord of the Rings, notably Faramir’s statement that he loves “the sword not for its sharpness” but for what it represents. Tolkien allows for a little more glory of war than Lewis (Gimli and Legolas making a game of how many orcs they kill). Still, Faramir’s cautious view, paired with the fact that the story’s heart is the peace-loving hobbits who fight when necessary without pursuing glory, makes it clear where Tolkien’s sympathies lie.

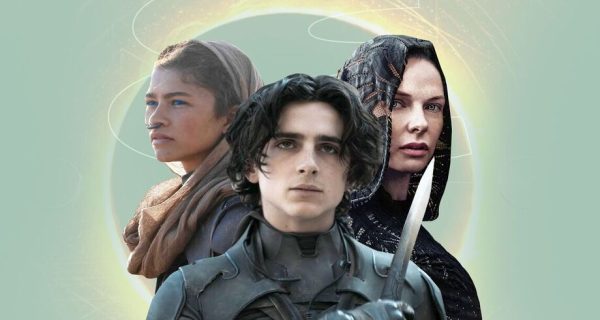

Tolkien’s contemporary Frank Herbert also presents a cautious view of war and glory in his sci-fi novel Dune. Guardian contributor Alison Flood discusses how alt-right readers have often misunderstood Dune as a tale glorifying power. After all, it is a story about a young prince becoming the prophesied messianic leader of a planet.

However, Flood points readers back to Jordon S. Carroll’s article in Los Angeles Review of Books, where Carroll reminds readers that there is more to the story. Carroll highlights how Paul Atreides’ rise to become “the messianic emperor of the Known Universe” isn’t a triumphant journey.

“… Paul begins the series as a tragic character but ends it as a grotesque one. Herbert himself saw the series as a critique of authoritarianism demonstrating for his readers that ‘superheroes are disastrous for humankind.’”

- Jordon S. Carroll, “Race Consciousness: Fascism and Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune’”

Thus, Herbert agrees with Tolkien about Might as Right being dangerous. However, he moves at a different pace to establish his position. Tolkien makes it clear from early on in The Fellowship of the Ring (Gandalf refusing Frodo’s offer to use the ring) that his saga is a story about the dangers of misusing power. Herbert’s first installment lays the foundation for a tragic story about power being misused, with the tragedy becoming clear in later installments.

From an adaptation perspective, the fact that Dune can be misread as a Might as Right narrative presents some interesting issues. It is a story about a boy becoming a man and finding power… and it’s not clear until the following books that he will use this power unwisely. As Willow Wilson DiPasquale warns, reading Herbert’s series is a unit matters because “without these sequels, the world of Dune is incomplete, our understanding of the author’s perspective incomplete” (Discovering Dune 177).

In this respect, the problem of adapting Dune is comparable to what hounded a fantasy film released two years before David Lynch’s Dune. Conan the Barbarian, written and directed by John Milius and released in 1982, was criticized by reviewers who perceived it as a fascist movie about a Germanic übermensch wreaking bloody revenge on his family’s killers. Milius maintained that his film wasn’t meant to be a standalone story, a complete statement about power. He hoped to make a Conan trilogy that showed his hero’s complex journey with violence and power.

“The trilogy was [planned so that] each one was about something. The first one was about strength, raw strength. The second one was about responsibility. The third one was about kind of tradition and loyalty.”

- John Milius interview, Conan Unchained: The Making of Conan the Barbarian

Ergo, Conan the Barbarian is a movie about a hero finding his Might, only learning later how to use it for Right.2 When David Lynch adapted Dune, he would face a similar problem but on a more complex level. Milius had to work with the fairly straightforward adventure material of Robert E. Howard’s short stories. Lynch had to deal with the many layers of (religious, cultural, literary, ecological) imagery that permeate Herbert’s novel.

Lynch’s vision for Dune was famously compromised by producers (a three-hour film trimmed to two hours, with Lynch disowning the result). Since the existing film doesn’t fit Lynch’s vision, it’s hard to tell how he handled the Might as Right problem.

What is clear is that the Dune movie released to theaters in 1984 loses whatever nuance the novel had about Paul’s rise to power. Dialogue and voiceovers (possibly added by the producers) refer multiple times to the messianic figure that Paul may become. He will a “super-being” who brings pain but rebirth. Some of these voiceovers use lines comparable to the book, without noticing how dark they sound.

“And now the prophecy. One will come. The voice from the outer world. Bringing in Holy War, the Jihad, which will cleanse the universe and bring us out of darkness…”

- Reverend Mother’s voiceover, Dune (1984)

Granted, talking about holy wars and jihad has darker overtones in a post 9/11 world. Even so, these references raise questions about how heroic Paul is… questions the film never engages with. Instead, the film goes directly from messianic and jihad references to Paul promising to avenge his father’s death, to “destroy the emperor and the baron.”

Ultimately, after years of garnering resources and training his “holy warriors,” Paul does take on Emperor Shaddam IV and Baron Vladimir Harkonnen. After a dramatic battle that defeats all his opponents’ forces, Paul addresses the Fremen and shows how much his extrasensory powers have developed. In a scene that doesn’t appear in the novel, Paul brings rain to the desert planet, something his followers have never seen before.

Whether it was Lynch’s intention or the producers trimming away all the nuance, the 1984 Dune is a clear celebration of Might as Right. Any complexity about Paul’s journey gets skipped over. To the extent the movie has a clear plot, its plot is about Paul taking a Conan-like revenge quest to kill his father’s murderers, then going beyond Conan-level heroism. By the end, he has achieved godlike status. While Herbert said in his introduction to his 1985 book Eye that he liked the 1984 film, he took issue with the ending where Paul becomes a godlike being: “[in my novel] Paul was a man playing god, not a god who could make it rain” (12).

When Denis Villeneuve was confirmed to be making a Dune movie in 2017, holy war and jihad references were certainly out. Furthermore, concerns about white savior narratives and alt-right politics meant that any Might as Right narrative would be scrutinized. Flood notes how when Villeneuve was asked about whether Dune is a white savior narrative in 2021, he called it “a criticism of the idea of a savior, of someone that will come and tell another population how to be, what to believe.”

To simultaneously tell a story about a hero’s rise and the dangers of his rise, Villeneuve uses an unusual approach.

First, he chooses to tell the story across two films—avoiding the rushed plot that made the 1984 film so puzzling.

Second, he handles Paul’s developing extrasensory powers in a new way. Like the 1984 film, viewers see Paul’s mother Jessica pushing him to practice powers to manipulate people. Like in the 1984 film, Paul gets hints from his mother that he could be a messiah. However, when Paul talks to his mother about the Bene Gesserit prophecies, Villeneuve makes their conversations foreboding rather than exciting. When Jessica talks to her son about the prophecies, Paul responds that he knows the Bene Gesserits control politics “from the shadows.” Later, on Arrakis, when his mother indicates the Bene Gesserit have planted stories about the messiah arriving, Paul calls this move “planting superstitions.” Instead of being fascinated about his destiny, Paul is hesitant or cynical.

Third, Villeneuve presents the visions quite differently. As in the 1984 film, Paul starts having visions early in the movie. However, while the 1984 film mostly uses image collages, Villeneuve depicts Paul’s visions as brief scenes. Paul gets flashes of locations and people minus dialogue or context. He tells his friend Duncan Idaho about something he saw in a dream: Duncan living alongside the Fremen, then Duncan dying in battle—a death Paul thinks he can prevent by fighting alongside Duncan. Shortly afterward, the Reverend Mother questions Paul about whether he ever dreams about things that happen in the future.

In this way, Villeneuve’s Dune makes Paul’s visions an explicit part of the plot (something the characters talk about), and easier to understand (scenes, not just psychedelic imagery). Further, the visions have an identifiable theme: foreboding about a dark future.

The foreboding increases as Paul’s visions increase. The camera cuts to these visions in the middle of other scenes, as if Paul is getting flash visions of the future. The visions increase until they coming during sleeping and waking hour, as if invading his life.

The visions increasingly become about war. Paul wearing golden armor as he fights on Dune. Familiar places on Dune burned to the ground.

Visions about a Fremen woman become especially detailed. Paul sees her walking across the desert multiple times. Eventually he sees her left hand (the hand, Merriam-Webster reminds us, associated with destruction or darkness) covered in blood. Then Paul sees her standing with him on a ship, overlooking his home planet Calladan, as if planning to invade it. This last vision happens when Paul is alone in the desert with his mother, who asks what he fears.

“It’s coming. I see a holy war spreading across the universe like unquenchable fire. A warrior religion that waves the Atreides banner and my father’s name! Fanatical legions worshipping and destroying at the shrine of my father’s skull! A war in my name! Everyone shouting my name!”

- Paul Atreides describing his visions, Dune (2021)

Unlike in the 1984 film, this time the references to holy war are clearly negative.

In short, Villeneuve creates a very different view of Paul’s rise to power. Paul wants justice for his father’s death, but has a strong sense of the terrible things that could happen if he becomes the long-awaited leader. The script (Paul’s suspicious view of the prophecies, the “it’s coming” speech) helps create this outlook, but the way Villeneuve structures Paul’s visions has equal impact. By making Paul’s visions easier to understand, Villeneuve makes it clear they are visions of a possible future. By having these visions appear at unexpected times throughout the film, Villeneuve makes his film simultaneously about Paul’s present (his rise to power) and his potential future (how he may become a tyrant).

The way that Villeneuve uses flash-forwards resembles the films of Nicolas Roeg, best known for directing the 1970s classics Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell to Earth. One of Roeg’s signatures was editing his scenes so they intercut with something else—scenes of the past or the future. In The Man Who Fell to Earth, viewers follow an extraterrestrial visitor on earth, but get recurring flashbacks of the extraterrestrial leaving his home planet. Don’t Look Now uses a variety of flashbacks and flashforwards, some of which may be psychic visions. Like Villeneuve’s Dune, Don’t Look Now has characters talking about visions—including one character who may be psychic without realizing it.

In Nicolas Roeg: The Enigma of Film, Danny Boyle and Steven Soderbergh describe how Roeg’s editing style affects the way his films present time. Soderbergh compares Roeg’s approach to a written paragraph where words can shift between past, present, and future tense. Boyle argues that Roeg captures multiple dimensions of time.

“Basically, all time is present in his films—past, future, and present, they’re all present, they’re all there for you in an order that he has chosen for you.”

- Danny Boyle interview, Nicolas Roeg: The Enigma of Film

Roeg’s approach to time opened up interesting possibilities—like how a film can show violence and its consequences. Soderbergh emulates Roeg’s editing style to talk about violence in his crime film The Limey. The story’s main story follows an English mobster Wilson tracking down his daughter’s killer in California. As Wilson tracks the killer, the film cuts to the past (showing Wilson’s past, his difficult relationship with his daughter), and sometimes to the future (close-up shots of a gun and upraised hands on a beach).

CrimeReads contributor Nick Kolakowski details how the editing choice “lends the film an unusually elegiac air, with nearly every scene adding weight to Wilson’s regrets and grief.” What could be a simple revenge thriller becomes a story about guilt and regret. Recognizing one’s own responsibility becomes more important than exercising violence to get vengeance.

Villeneuve’s use of flashforwards is a little more conventional than Soderbergh. Still, they both use Roeg-esque techniques to tell a story where the past or future invades the present to create a strong sense of responsibility and guilt.

By employing Roeg-esque techniques, Villeneuve applies foreboding to a story about a hero’s rise to power. Thus, he avoids the conundrum that filmmakers like Milius and Lynch have faced. He makes a story about a hero finding their Might, but makes sure the story is filled with warnings about how Might shouldn’t be mistaken for Right.

Time will tell how Villeneuve will handle these elements in his continuation of the Dune saga.

1. At least one scholar has indeed suggested Tolkien’s WWI experiences may explain his treatment of war: Holly Ordway suggests this is why Tolkien took suffering very seriously in his stories, and disliked the works of Inklings guest E.R. Eddison who took a more flippant view of suffering (Tolkien’s Modern Reading 214).

2. Interestingly, Milius’ hero origin plot structure, where the hero kills and later learns he must be wiser, has recently appeared in the Dark Knight trilogy and the movie Man of Steel. This may suggest that Milius’ concept becomes less polarizing when applied to comic book characters, which is ironic given how many times Milius emphasized in interviews that Conan the Barbarian is not a comic book movie, but something more serious.

An earlier version of this essay was presented July 22, 2022, at “DUNE Zoom, An Inkling Folk Fellowship Discussion.”

Sources Cited

Carroll, Jordon S. “Race Consciousness: Fascism and Frank Herbert’s ‘Dune.’” Los Angeles Review of Books, November 19, 2020. lareviewofbooks.org/article/race-consciousness-fascism-and-frank-herberts-dune/

Conan the Barbarian. Directed by John Milius. Dino De Laurentiis Corporation and Universal Pictures, 1982.

Conan Unchained: The Making of Conan the Barbarian. Directed by Laurent Bouzereau. Universal Studios Home Video, 2000. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jiQ9rUgQcXI.

DiPasquale, Willow Wilson. “Shifting Sands: Heroes, Power, and the Enviroment in the Dune Saga” in Discovering Dune edited by Dominic J. Nardi and N. Trevor Brierly, 177-192. McFarland & Company, 2022.

Don’t Look Now. Directed by Nicolas Roeg. British Lion Films, 1973.

Dune. Directed by David Lynch. Universal Pictures, 1984.

Dune. Directed by Denis Villeneuve. Warner Bros. Pictures, 2021.

Herbert, Frank. Eye. 1st ed., Berkely Books, 1985.

Flood, Alison. “Dune: science fiction’s answer to Lord of the Rings.” The Guardian, October 18, 2021. theguardian.com/books/2021/oct/18/dune-science-fiction-answer-to-lord-of-the-rings-frank-herbert-neil-gaiman

Kolakowski, Nick. “‘The Limey’: How Steven Soderbergh Subverted the Classic Revenge Film.” CrimeReads, June 14, 2021. crimereads.com/the-limey-soderbergh/

Lewis, C.S. The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. 1st ed., Geoffrey Bles, 1950.

—. The Horse and His Boy. 1st ed., Geoffrey Bles, 1954.

Nicolas Roeg: The Enigma of Film. Supplementary documentary on Criterion DVD of Don’t Look Now, 2015. criterion.com/films/27928-don-t-look-now.

Not Stated. “The Left Hand of (Supposed) Darkness.” Merriam-Webster, Date Not Stated. merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/sinister-left-dexter-right-history.

Ordway, Holly. Tolkien’s Modern Reading. 1st ed., Word on Fire Academic, 2021.

The Limey. Directed by Steven Soderbergh. Artisan Entertainment, 1999.

The Man Who Fell to Earth. Directed by Nicolas Roeg. British Lion Films, 1976.

“Thesis Theater: Miriam Davidson, ‘Nonviolent Countercurrents in Tolkien’s Epic of War.’” Signum University, May 26, 2022. youtube.com/watch?v=gMYr8F9yz7I.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings. 1st ed., Allen & Unwin, 1968.

White, T.H. The Once and Future King. 1st ed., G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1958.