In the medieval period and up to around 1540, St. Etheldreda was still held in great esteem throughout England. Pilgrimages were made to her shrine in Ely Cathedral and badges were worn by those who had completed the pilgrimages. She was a patron of chastity and was invoked for help against infections of the throat and neck.

To this day, the Blessing of Throats is an important annual event at St. Etheldreda’s in London. Lace and silk necklaces are associated with her cult and were sold on her feast day in Ely at St. Audrey’s Fair. The work “tawdry” derives from this, referring to the inferior quality of these tokens. If you go to Ely Cathedral today, there is an inscription on the floor marking the location of her shrine, “Here stood the shrine of Etheldreda, saint and queen, who founded this house AD 673” (Ely Cathedral).

Her church in Holborn, known as St. Etheldreda’s church, is the oldest Roman Catholic church still surviving in England, and she continues to be venerated in her hometown of Ely at St. Etheldreda’s church, where her shrine and relics are contained. She is also venerated as a saint in the Orthodox Church. St. Etheldreda’s Church was the town chapel of the Bishops of Ely from about 1250 to 1570. Today, it is the oldest Catholic church in England and one of only two remaining buildings in London from the reign of Edward I.

Æthelthryth could be seen by many Catholics today as a role model and an inspiration to the faithful. An interesting relic is to be found in the Catholic church of St. Etheldreda in the Cambridgeshire town of Ely. It is said to be the hand of an Anglo-Saxon queen and abbess, St. Æthelthryth or St. Etheldreda. Considering that she is said to have died in 679, this is a remarkable object both for Catholics and for historians of the period. The 23rd of June is the feast day of Æthelthryth, an Anglo-Saxon queen of Northumbria and founder of a double monastery at Ely, who took a vow of celibacy despite being married twice. Her relics are still to be found in Ely and London today.

Relics are religious objects generally connected to a saint, or some other venerated person, and they aren’t necessarily just bones. Catholic belief in the power of relics, the remains of a holy person, or objects with which they had contact, is as old as the faith itself and developed alongside it. Relics were more than mementos. The New Testament refers to the healing power of objects that were touched by Christ or his apostles and this belief continued during the medieval period. The body of the saint provided a spiritual link between life and death, between man and God. Fuelled by the Christian belief in the afterlife and resurrection, in the power of the soul, and in the role of saints as advocates for those who had departed this life. Indeed, the veneration of relics in the Middle Ages could be said to almost rival the sacraments in the daily life of the medieval church. During the Middle Ages, it was expected that every altar should contain a relic of a saint. This tradition continues in the Catholic church today.

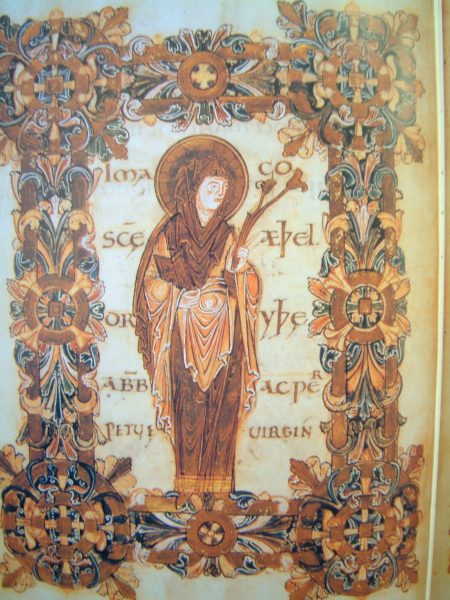

Let’s examine the evidence surrounding Æthelthryth. There are a number of accounts of Æthelthryth’s life in Latin, Old English, Old French, and Middle English. The most famous is an account of her life by the Venerable Bede in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Angolorum.

Princess Æthelthryth was said to be the daughter of King Anna, who was a king of East Anglia. Æthelthryth was probably born around 636 AD in Exning, near Newmarket in Suffolk. One of the four saintly daughters of Anna of East Anglia, who all eventually retired from secular life and founded religious houses. Æthelthryth was regarded as a very spiritual young woman and she reportedly wanted to become a nun from a young age. Æthelthryth, whilst still in her teens, made an early first marriage, probably what we would now call an arranged marriage, around 652 to Tondberct, chief or prince of the South Gyrwe who was likely to have been considerably older than her. She managed to persuade her husband to respect her vow of perpetual virginity that she had made prior to their marriage. After his early death in 655, she went to live at a manor on the Isle of Ely, which she had received from her husband as a gift.

Æthelthryth subsequently remarried, again probably for political reasons in 660, this time to Ecgfrith of Northumbria, then said to be still a teenager and younger than Æthelthryth. Shortly after his accession to the throne in 670, Æthelthryth apparently announced her intention to become a nun. This step possibly led to Ecgfrith’s long quarrel with Wilfrid, Bishop of York who was her confidant and spiritual advisor. One account relates that while Ecgfrith initially agreed that Æthelthryth should continue to remain a virgin, but in about 672 he wished to consummate their marriage and even attempted to bribe Wilfrid to use his influence on the queen to convince her. This tactic failed and the king tried to take his queen by force. Æthelthryth fled and made her way to Coldingham on the Scottish coast, north of Berwick Upon Tweed, but then still part of Northumbria. She was also said to have given money and land to Wilfrid to establish a monastery at Hexham around this time.

At Coldingham, under the careful guidance of Saint Æbbe, Etheldreda finally became a nun. Etheldreda stayed at Coldingham for about a year before eventually making her way back to Ely with two faithful nuns where, as well as founding a religious community, she also built a magnificent church on the ruins of one founded by the efforts of St. Augustine himself but laid waste by war. Etheldreda was quite a revolutionary. She is said to have set free all the bondsmen on her lands and for seven years led a life of exemplary austerity.

“It is told of her that from the time of her entering the monastery, she would never wear any linen but only woollen garments, and would seldom wash in a hot bath, unless just before the greater festivals, as Easter, Whitsuntide, and the Epiphany, and then she did it last of all, when the other handmaids of Christ who were there had been washed, served by her and her attendants. She was renowned for her humility and service to others around her as well as her asceticism and piety. She was said to seldom eat more than once a day, except on the major festivals, or for some exceptional reason. Her habit, except when serious illness prevented her, from the time of matins till daybreak, was to continue to pray in the church. Some also say, that by the spirit of prophecy she not only foretold the pestilence of which she was to die, but also, in the presence of all, revealed the number of those that should be then snatched away from this world out of her monastery.” (A. M. Sellar, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of England, George Bell & Sons, 1907).

It is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Æthelthryth founded a double monastery at Ely in 673, which was later destroyed in the Danish invasion of 870. After its restoration in 970 by Ethelwold, it is said to have become the richest abbey in England after Glastonbury.

Etheldreda died about 680 reportedly from a tumour on the neck, reputedly as a divine punishment for her vanity in wearing necklaces in her younger days. In reality it may have been as a result of a plague which also killed several of her nuns, many of whom were related to her. Seventeen years after her death, her body was reported to be incorrupt, in other words, it did not appear to have decayed. Wilfred and her physician, Cynefrid, were among the witnesses. The tumour on her neck, cut by her doctor, was found to be healed. The linen cloths in which her body was wrapped were as fresh as the day she had been buried. Her body was placed in a stone sarcophagus of Roman origin, found at Grantchester, and reburied. The story of the Northumbrian queen preserving her chastity as a sign of her devotion to God, fleeing from her second husband Ecgfrith when he tried to rape her and travelling back to her homeland to found the monastery at Ely in 679 obviously struck a deep chord in the medieval psyche.

After her death, devotion to her seemed to have spread rapidly, as people claimed to have received help and favours through what they were convinced was her powerful intercession in Heaven. And when, through popular demand, it was decided to remove her to a more fitting tomb, it was found that even after 15 years in wet earth her body was still in a perfect state of preservation. According to Bede, (Historia Ecclesiastica), her body remained uncorrupted after death, a sure sign she had not been defiled.

When the Normans began building the present Cathedral at Ely and moved her body in 1106, it was again reported to be still incorrupt. That was nearly 450 years after her death. Bede, in his History of the English Church, told how after her death, Æthelthryth’s bones were disinterred by her sister and successor, Seaxburh and that her uncorrupted body was later buried in a white, marble coffin.

In 695, Seaxburh moved the remains of her sister Æthelthryth, who had been dead for sixteen years, from a common grave to the new church at Ely. The Liber Eliensis, a twelfth century chronicle of history, written in Latin in Ely and composed of three books. It reports that when her grave was opened, Æthelthryth’s body was discovered to be uncorrupted and her coffin and clothes proved to possess miraculous powers. A sarcophagus made of white marble was taken from the Roman ruins at Grantchester, which was found to be the right fit for Æthelthryth. Seaxburh supervised the preparation of her sister’s body, which was washed and wrapped in new robes before being reburied. She apparently oversaw the translation of her sister’s remains without the supervision of her bishop, using her knowledge of procedures gained from her family’s links with the Faremoutiers Abbey as a basis for the ceremony.

Virginia Blanton (“Signs of Devotion: The Cult of St. Æthelthryth in Medieval England 695-1615,” 2010) argues that the safe and inviolable monastic space is a symbol of her inviolable virgin body. In other words her body could be compared to the sacred and sacrosanct nature of the monastic space and enclosure (“Women’s Space, Place and Gender in the Medieval Church,” V, Blanton, 2010). Elsewhere, she argues that the saint was a popular symbol of purity and that her incorrupt body reflected her devotion and dedication to the inner spiritual life that she led.

“Here is one shrine, within which the marble sarcophagus containing the virgin body of St. Æthelthryth is enclosed, turned in the direction of her own altar, just as the exalted lady, entirely whole, entirely uncorrupted, rests in the tomb which, we believe, had been prepared for her at God’s command by the hands of angels.” (Tota Integra, Tota Incorupta: The Shrine of St. Æthelthryth As Symbol of Monastic Autonomy, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, pp227-267, Duke University Press 2002).

For a long time during the Middle Ages there was an annual St. Etheldreda’s fair in Ely. Sometimes it was referred to as St. Audrey’s Fair. It often specialised in selling lace to go around the neck. Some of this lacework was reputedly of such poor quality that it was referred to as ‘tawdry’ after St. Audrey. During the medieval period the Abbeys or Cathedral churches of Durham, Glastonbury, Salisbury, Thetford, Waltham and York all claimed to have relics, or small parts of the body of St. Etheldreda. How accurate these claims were, is difficult to verify.

Besides the principal relic of the body of St. Etheldreda, the cult of St. Etheldreda seems to have also involved the distribution of lace necklaces and other objects which were claimed to have been associated with St. Etheldreda. Records of the visitation of Dr. Layton and Dr. Leigh in 1536 make reference to cloths for women with sore throats and sore breasts, a comb of St. Etheldreda for women with headaches and a ring of St. Etheldreda for women seeking relief when ‘lying-in’ in childbirth.

During the medieval period, Ely cathedral was known as the Cathedral Church of St. Etheldreda and St. Peter, but the dedication was changed at the Reformation to the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity. The ancient shrine of the saint, which had been a focus of pilgrimage until then, was demolished around 1541. Parts of the shrine are said to have been found in different parts of Ely in more recent times. Painted panels with scenes from the saint’s life were said to have been used as a cupboard door in an Ely house in the 1780s. There was said to be a small eighth-century carved frieze found in a barn wall at St. John’s Farm near Ely, which is thought by some to have come from the shrine. The shrine was apparently made of stone rather than marble as was commonly thought at the time. Official records show that some 361 ounces of gold and 5,040 ounces of gold and white plate were taken from the shrine into the royal treasury. Thus ended the medieval cult of St. Etheldreda of Ely.

Today there is a chapel in Ely Cathedral dedicated to her. There is a statue of the saint to be found there and visitor or pilgrims are encouraged to say a prayer and light a candle.

It does not appear to be recorded what happened to the body of the saint but in 1541 it was recorded that her body still appeared to be incorrupt.

A relic of St. Etheldreda, consisting of her left hand, was reputedly found preserved in a separate reliquary, hidden in a priest’s hiding hole in a house in Sussex in about 1811. It was apparently presented to the Duke of Norfolk and passed down to the community of Dominican Sisters at Stone in Staffordshire. The hand was found on an engraved silver plate on which was written ‘Manus Sanctae Etheldredae DCLXXIII.’ (The hand of St. Etheldreda 673 AD). The plate itself was of a tenth-century style, suggesting that the hand had been separated from the rest of St. Etheldreda’s body at around the time of the tenth century.

It was reported in 1876 that when the hand was found it was “perfectly entire and quite white (but) exposure to the air has now changed it to a dark brown and the skin has cracked and disappeared in several places” (Alexander Wood, St. Etheldreda and her Churches in Ely and London: A Preliminary Notice of the Catholic Memorials and Missions in the Vicinity of the Latter and a Supplementary Account of Ely House, (A lecture read at St. Etheldreda’s Ely Place, 2 March 1876), Papers in the Cambridgeshire Collection C52 p.16)

A small part of the hand of the saint was given by the nuns at Stone to St. Etheldreda’s Church in Ely Place, Holborn, London in 1950 and in 1953 they donated the rest of the relic to St. Etheldreda’s church in Ely where it remains today. St. Etheldreda’s Church in Ely Place in Holborn is dedicated to the saint. It was originally part of the palace of the bishops of Ely.

After the Reformation, the palace was used by the Spanish ambassadors, enabling Catholic worship to continue in the church. In 1620, the Spanish Ambassador, the Count of Gondomar, a face so loved by the artist El Greco, moved into Ely Place. The Bishop’s Palace was his residence and mass was again allowed to be said in St. Etheldreda’s, because an ambassadorial residence and grounds are considered part of the country they represent. To hear mass was still punishable by death for English Catholics but despite the dangers they flocked to St. Etheldreda’s. It was written at the time that more persons were drawn to mass at Gondomar’s little private chapel in Holborn than anywhere else.

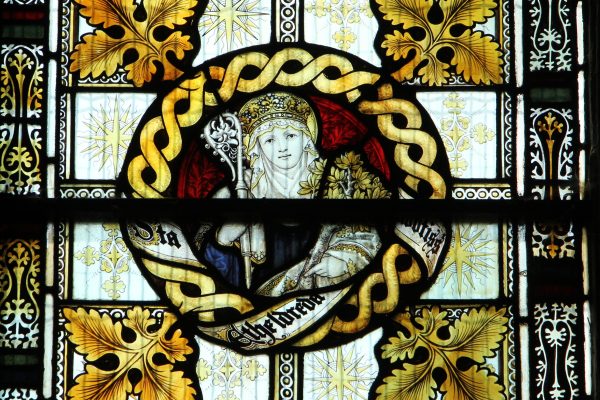

Since 1878 it has once again become a Catholic church and later, the home of the relic of the saint. St. Etheldreda’s church is the oldest Catholic church in Britain and dates to the reign of Edward I. It will always be a place of prayer and remembrance of this pure and holy queen of Northumbria. There is also a St. Etheldreda’s Church in White Notley, Essex, which is a Church of England parish church, of Saxon construction, built on the site of a Roman temple, with a large quantity of Roman brick in its fabric. The church has a small Mediaeval English stained-glass window, depicting St. Etheldreda, which is set in a stone frame made from a very early Insular Christian Roman Chi Rho grave marker. Her relic in the Catholic church in Ely is a tangible reminder of the medieval cult of the saint and an example of a holy and devout Christian life dedicated to God.

Bibliography

Blanton, Virginia. “Ely’s St. AEthelthryth: The Shrine’s Enclosure of the Female Body as Symbol for the Inviolablility of Monastic Space.” SUNY Press, 2005. academia.edu/817925/Elys_St_AEthelthryth_The_Shrines_Enclosure_of_the_Female_Body_as_Symbol_for_the_Inviolablility_of_Monastic_Space.

—. Tota Integra, Tota Incorupta: The Shrine of St. Æthelthryth As Symbol of Monastic Autonomy, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2002.

—. Women’s Space, Place and Gender in the Medieval Church, The English Historical Review, (collection of essays) Volume CXXIII, Issue 505, December 2008, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008.

Selwood, Dominic. “On this day in 679: Æthelthryth, Anglo-Saxon princess and saint, dies at Ely.” The Telegraph, June 23, 2017. telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/23/day-679-thelthryth-anglo-saxon-princess-saint-dies-ely/.

Not Stated. “About Æthelthryth: Abbess of Ely (n/a-0679).” peoplepill.com/people/aethelthryth.

Not Stated. “Who was St. Etheldreda.” ElyDiocese.org, September 15, 2022. elydiocese.org/about/history/all-about-st-etheldreda.php.

—. “St. Etheldreda’s Church.” StEtheldreda.com, Not Stated. stetheldreda.com/index.php/history-of-st-etheldredas/#1.

Not Stated. “Bede on St. Etheldreda.” StEtheldreda.com, Not Stated. stetheldreda.com/index.php/history-of-st-etheldredas/bede-on-st-etheldreda/.

Sellar, A M. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of England, George Bell & Sons, London, 1907.