Dr. Diana Pavlac Glyer (PhD, University of Illinois, 1993) has had a diverse writing and editing career. It began with journalism, covering musicians like Amy Grant and Randy Stonehill for magazines like Cornerstone and HIS. Since then, her work has expanded to include a book on spiritual development (Clay in the Potter’s Hands) and extensive work as an Inklings scholar.

A full list of her Inklings scholarship would take pages, so a summary will have to do. Her reviews and journal articles have appeared in publications like Tolkien Studies, Mythlore, and Christian Scholar’s Review. She has been part of the journal Sehnsucht (first as an associate editor, now as an advisory board member) since 2014. In 2007, she published The Company They Keep, a groundbreaking and multi-award-winning study of how the Inklings influenced each other’s work. The book revolutionized how scholars discuss the Inklings as a literary community. Her 2016 book Bandersnatch covers the subject with a different focus: the practical lessons we can learn from their example.

Glyer has taught or lectured at various schools, including Northwind Seminary and Fuller Theological Seminary. Since 1995, she has been a faculty member of Azusa Pacific University, and currently serves as a professor in the APU Honors College. Rather than writing a senior thesis, honors students collaborate on a year-long process of writing a book together. One such project resulted in the 2021 book A Compass for Deep Heaven, co-edited by Glyer with Julianne Johnson. The book leads readers through C.S. Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy (also known as the Ransom or Space Trilogy).

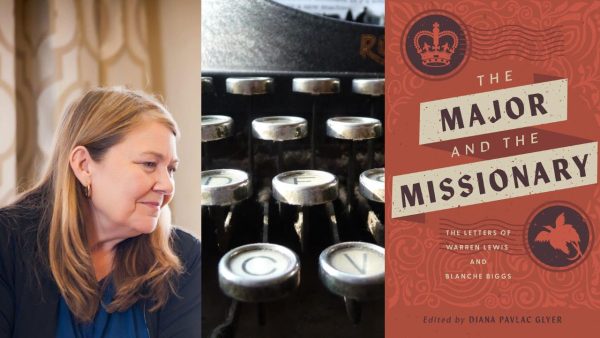

Her latest editing project is The Major and the Missionary: The Letters of Warren Hamilton Lewis and Blanche Biggs, published by Rabbit Room Press. Major Warren “Warnie” Hamilton Lewis (1895-1973), older brother of C.S. Lewis, has an interesting reputation. Most Inklings scholars know that Warren had a full career in the Royal Army Service Corps, then retired in 1932 (receiving the rank of major when he returned to the service during World War II). After serving in various countries during his army service, Warren lived the rest of his life with his brother at The Kilns, a house in Oxford. Warren’s post-army career included attending Inklings meetings, writing books on French history, and serving as his brother’s secretary. Following his brother’s death in 1963, Warren edited the first edition of Letters of C.S. Lewis.

Few know about another chapter of Warren’s life, a remarkable story that doesn’t revolve around his brother. From 1968 to 1972, he corresponded with Dr. Blanche Biggs, a missionary doctor working in Popondetta, Papua New Guinea. The Major and the Missionary is the first time that their letters have been published.

Glyer was kind enough to answer a few questions about the book.

INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

Can you give us a general idea of how this project started?

It happened by accident, or, perhaps, Providence. Back in 1998, I was spending several weeks at the Wade Center doing research, spending day after day studying letters and diary entries and manuscripts related to the Inklings. Then I stumbled across this correspondence. On first read, I was hooked. Warren and Blanche are thoughtful, articulate, and thoroughly engaging. Together, they explore and debate politics, faith, and current events, and share their personal hopes, challenges, and fears. It’s a rare and wonderful correspondence.

How long did it take to complete the book?

When I first read the letters, I had to make a hard decision: whether to focus my attention on this extraordinary letter collection OR continue to make progress on The Company They Keep. I turned aside from the letters with real regret until Company and Bandersnatch were published. It has been such a joy for me to finally return to this project.

Did you consult other books on Warren (for example, Brothers and Friends, edited from his diaries) while you were editing this book?

I did: I studied Warren’s diaries, his seven books on French history, and other unpublished papers. I also dug into everything I could find about Dr. Blanche Biggs. There is a collection of her papers at the Fryer Collection at the University of Queensland. The staff there was very supportive at every stage of my research.

I also learned a great deal from John Biggs. He is Blanche Biggs’ nephew and godson. He answered questions, provided photographs, and shared a book that he had written about his family’s history. He kindly wrote the foreword to The Major and the Missionary.

How did Blanche Biggs come to correspond with Warren?

I’ll let Blanche tell that story; here is an excerpt from her first letter:

“I hope that you have the patience in answering letters from strangers that your brother had. This letter is written from curiosity, but there is some sort of purpose behind it. I am just finishing the C.S. Lewis Letters edited by you, and of course, I bought it only because so many others of his books have been a help and enjoyment to me in the past. Your book rounds out one’s mental picture of your brother in a most satisfying way. Now to the question: how did all those letters survive, so as to be available to you for publication?”

Blanche confesses that she tends to hoard letters: she keeps carbon copies of her letters, she saves up the letters she receives from others, and, at this point, she has acquired quite a collection. Her purpose in writing to Warren Lewis? She wants his advice about whether to have a bonfire and burn the lot of them or to save all these letters. In her first letter to Warren, she writes, “Some of my letters and papers might be useful in the future, even after my death.” And, indeed they are.

You spoke with Inkling Folk Fellowship about the book and noted the real treasure here is that Blanche kept carbon copies of her letters before sending them out. For readers who don’t work in archives, what makes that an amazing find?

I love working in archives among special collections like the Wade Center and the Fryer Collection. But when you are working with old letters, there is always a great frustration: you only have one side of the conversation! Think about a book like Letters of C.S. Lewis. As I read them, I am constantly wondering, “What question or comment is Lewis responding to? How is he tailoring his thoughts to match the needs of his correspondent?” In short, “What is the larger context of this conversation?”

Since Blanche kept carbon copies of her letters and saved everything Warren sent her (including notes and postcards!) and then graciously donated all of it to the Wade Center, we have something that is extremely rare: we have the full and complete correspondence. We have both sides of the conversation. This fact alone makes these interesting letters a rare treasure.

Rabbit Room Press is an interesting home for this project—a great publisher, but not an academic press like the ones that have released your earlier books. How did you become connected with them?

When I first read these letters, I learned a great deal about the Lewis brothers and about the Inklings. I loved Blanche and Warren, and I admired the way they express themselves with candor and aplomb. But what really enchanted me was the story itself. The people are real, and the letters are real, but much more than that: it was the dramatic way the narrative unfolds. The story is so captivating as these two mature Christians who live half a world apart become pen friends, then confidants, and then grow together in intimacy and deep affection. I’ve written a stage adaptation that highlights this compelling story. And while the Rabbit Room Press celebrates great books, they also have such a capacious vision for art, music, theatre, film, and other creative realms. They have been ideal partners in the process of bringing The Major and the Missionary to life.

While we don’t know much about Warren, what little we know suggests someone who wasn’t likely to befriend women. He never married. He clashed with Janie Moore throughout her years living at the Kilns.1 He worried that his brother marrying Joy Davidman would reinstitute a matriarchy,2 although he soon warmed up to Joy. What do you think drew him to befriend Blanche Biggs?

Warren and Blanche had a great deal in common. Both were Anglicans, both were older adults, both writers who absolutely love books and are widely read. And then there’s this small detail: both owned motorbikes!

But I think there is an even larger issue that unites them. Both of them lived to some extent in the shadow of a larger purpose. Warren was dedicated to supporting and maintaining the legacy of C.S. Lewis. Blanche was utterly devoted to her work on the mission field. Both lived long and productive lives, but I think both felt a longing for someone who was interested in them, who reached out to them, and who was a safe haven for their own fears and longings.

I mean, I think about the circumstances surrounding the very first letter from Blanche. It’s October 1968. C.S. Lewis died five years earlier, and Warren’s daily routine is dominated by answering his brother’s ongoing, voluminous correspondence. Then one day, Warren gets a letter addressed to him, one that shows genuine interest in him and appreciation for his work, from someone who asks questions about his life and is open and eager to hear what he has to say. No wonder more than 70 letters travel back and forth between them, sent from a small mission hospital in Popondetta to a little house in Oxford and answered by return post.

Missionary life (and I say this is a second-generation Missionary Kid) tends to get stereotyped a bit, especially if it involves remote locations. Can you give us an idea of what Blanche Biggs did—how the missionary and doctor roles went together, what organization she worked under?

Blanche was born and raised in Scottsdale, Tasmania. She was appointed by the Australian Board of Missions to serve in Papua New Guinea as a doctor and hospital administrator, and she served from 1948 to 1974. As a medical doctor on the mission field, she did it all: delivering babies, performing surgeries, and administering vaccines, to name a few.

On November 25, 1948, she offered this account to readers of her newsletter:

“Since I wrote last, I have done a fair amount of traveling, finally collected all my straggling bits of luggage and unpacked; and can fairly say that I have settled in. There have been odds and ends of surgery, none of it major; the most alarming thing I have done so far has been to repair a man’s arm after a crocodile had finished with it. Both the patient and I, I think, offered up thanks that it was a small crocodile.”

On January 1, 1975, Blanche Biggs was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in honor of her work as a medical missionary.

Outside of these letters, has anyone else written about Blanche Biggs’ life?

In her first letter to Warren, Blanche asks whether she should burn her large collection of letters and papers. Warren shares his own experience as an author who first published late in life, and he encourages her:

“As regards your own material I would strongly urge you neither to burn it or hand it over to anyone else, but retain it and when you retire, have a go at making a book out of it yourself. I can see from your letter that you are the kind of person who would have no difficulty in writing and I regard ‘nearing 60’ as middle age—being myself 73.”

Nineteen years later, in 1987, Blanche gathered her first-hand accounts of life on the mission field and published them in a book entitled From Papua with Love.

During your Inkling Folk Fellowship talk, you mentioned a key struggle with discussing Warren has been how some perceive his alcoholism—something his generation discussed in moral terms, not clinical ones. We might argue that, intentionally or not, it affects how Inklings biographies frame Warnie’s life after his brother died—that Warren didn’t do much except edit a letter collection, drink too much, and worry he should have been Boswell to his brother’s Dr. Johnson.3 Did editing The Major and the Missionary give you any insights into this area?

There has been a tendency to abbreviate Warren’s life down to only two facts: he was C.S. Lewis’s brother, and he struggled with alcoholism. No one’s life is that narrow. He was an army officer, a member of the Inklings, a gifted and accomplished writer, a world traveler. Warren was a man of broad interests and wide experiences. It frustrates me to see anyone labeled and summarily dismissed based on one or two aspects of their life. It grieves me to see anyone reduced to little more than the sum of their struggles.

Perhaps it will help to offer this corrective: alcoholism is a complex disease, and it strikes different people in different ways. After he retired from the army, Warren was vulnerable to alcoholic binges when triggered by stress, insomnia, depression, or loss.

The image that emerges from these letters is not of a man who spends day after day in an alcoholic daze. It is a man with a lively intellect, a true zest for life, an interest in world events, and a warmth and charity toward Blanche and her world.

What kind of impact do the letters suggest Warren had on Blanche’s life—do we see him helping her process problems with co-workers, discuss the work’s spiritual or moral questions, anything like that?

One of the hardships that missionaries face is the challenge of processing their disappointments and venting their frustrations. As the chief administrator of a remote missionary hospital, Biggs doesn’t really have anyone she can confide in. In the letters, we learn of a scandal at the hospital. Biggs is dismayed and “pours out her heart” to Warren. At first, he minimizes the situation, and then, in later letters, he offers significant understanding and support. She reflects, “I still don’t know if it was right or wrong of me to pour out my troubles in your last letter. There are so many people one cannot pour them out to.” She thanks for his help as “an uninvolved ear to besiege” (Letter 20). Warren replies, “Be assured that if you care to unburden yourself to me, you will find a sympathetic even if unhelpful listener” (Letter 21).

You have mentioned that there’s a bit of flirtation between Blanche and Warren in some letters. Since there is no Shadowlands: The Next Generation, I assume the flirtation never became anything serious, but it is surprising. What was your reaction when you discovered it?

There is a decided shift in the letters as time goes by: Biggs suggests they call each other by their first names, and they do. Warren starts to sign his letters, “yours, affectionately,” and Blanche does the same. When Warren hears that one of Bigg’s friends will be visiting Oxford, he writes, “I shall look forward to meeting your friend if it proves at all possible, but I mean no disparagement to her if I say that I am even more anxious for a visit from you. Well, only mountains never meet and I shall live in hopes.”

You mention Shadowlands, the story of how C.S. Lewis met Joy Davidman, the great love of his life. And that wonderful relationship began when Davidman wrote a letter to C.S. Lewis and the two became pen friends. I can’t help but wonder if Warren was reminded of that relationship as his own relationship with Blanche deepened.

While there hasn’t been much written about Warren, a major advance came at the end of 2022, with the Don W. King biography, Inkling, Historian, Soldier, and Brother. Did you know about King’s biography before it appeared? If so, was he able to provide any insight into your project?

Don and I corresponded and shared our work in progress as we were writing about Warren Lewis. I am very glad that now we all have access to Inkling, Historian, Soldier, and Brother, his fact-filled account of Warren’s interesting life.

I know you are currently writing a book about the writing process, and no doubt have plenty of other projects in the making. What’s one that you’d especially like to share?

I am excited to be working on a series of four books about writing. I draw from more than 40 years as a writer and a teacher of writing. The first book in the series is called A Writer’s Process, and it is designed for anyone who ever wanted to write a book but doesn’t know where to start. My PhD is in Composition Studies, and the process of compiling my very best advice for writers feels like coming home.

The Major and the Missionary can be purchased through the Rabbit Room Store and other major book retail outlets. More information about Glyer’s future projects can be found on her website.

Interviewer Notes:

- Janie Moore (1872-1951) was the mother of C.S. Lewis’ WWI battle comrade Paddy Moore, who died in 1918. Honoring an agreement to care for Paddy’s mother and sister if Paddy didn’t survive, Lewis shared a home with Mrs. Moore and her daughter, Maureen, after his war duty ended in 1919. Warren refers throughout his diaries and letters to his distaste for Janie Moore, whom he perceived as difficult and treating his brother like a servant. Interview records unsealed after Walter Hooper’s 2021 death indicate that Lewis had a romantic relationship with Janie Moore for several years, but it had become a platonic foster-mother, foster-son relationship by the time Lewis became a Christian in his thirties. Dr. Bruce Charlton notes in a blog review of Don W. King’s biography that Warren apparently didn’t know the early relationship had illicit elements, which may explain his confusion at his brother’s long-suffering patience for Janie Moore’s behavior.

- C.S. Lewis initially married Joy Davidman (1915-1960) in a civil union for her to maintain British residence, which led into a romance (depicted in the play and movies Shadowlands). In a November 5, 1956 diary entry, six months after Lewis’ civil union with Davidman, Warren observed that Lewis had assured him the union wouldn’t change anything but it became clear it would become a full marriage (Brothers and Friends 245). While pleased to have Davidman as a sister-in-law, Warren observed the romance wasn’t long after Mrs. Moore’s death: “the gap between the end of the Ancien Regime and the Restoration had lasted for less than four years” (ibid).

- Brothers and Friends includes a diary entry where Warren laments he could have done more to memorialize his brother: “with what zealous care I would have Boswellized him” (270). James Boswell wrote an acclaimed biography of Dr. Samuel Johnson, which C.S. Lewis included in a list of 10 books that influenced his worldview. Will Vaus discusses the Boswell biography in C.S. Lewis’ Top Ten: Influential Books and Authors, Volume Three.

Thank you!