Click here to read the introduction and here to read the previous chapter.

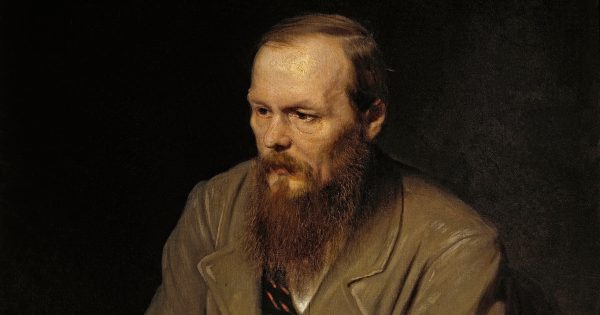

There’s an important little passage in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov which has in it the seed of an important argument. The great thing about this book, however, is that it is possible to pick any number of little passages that say something profound and important.

Alyosha, who has been living in a monastery, has the following conversation with his brother Ivan who tends towards atheism:

“I understand it all too well, Ivan: to want to love with your insides, your guts—you said it beautifully, and I’m terribly glad that you want so much to live,” Alyosha exclaimed, “I think everyone should love life before everything else in the world.”

“Love life more than its meaning?”

“Certainly, love it before logic, as you say, certainly before logic, and only then will I also understand its meaning. That is how I’ve long imagined it. Half of your work is done and acquired, Ivan: you love life. Now you only need to apply yourself to the second half, and you are saved.” (pp. 230-231).

Alyosha is above all trying to save his brother. Ivan, through the course of the novel, makes a subtle but penetrating attack on Christianity. For Ivan, there is no God and no immortality. Dostoevsky puts forward one of the most powerful attacks on Christianity, but he also puts forward a very profound defence. In this little passage and others, there is put forward the essence of Christian existentialism. It is from life and individual experience that it is possible to become convinced of the truth and to obtain faith.

I watched a film recently about the great scientist Stephen Hawking. It was called The Theory of Everything. At one point, Hawking at a press conference says something along the lines of that he has explained everything in the universe. There was no need for God. There was no room for God. By explaining everything he had, as it were, left no room for God – and, indeed, explained Him away. Everything that modern physics puts forward is, no doubt, true or as true as anything can be considering the present state of our knowledge. It is folly to question what great minds have discovered about the universe. But if physics describes everything and there is no room for God, it would appear that faith can no longer be possible. Where is God if Hawking can explain everything?

Hawking journeys outwards and his great mind travels outwards into the universe and backwards in time to the beginning of time. But his journey is in the wrong direction if he wants to find God. God is not in the journey outward. Rather, God is found within. This does not, of course, mean that God is in me, or that I am God. That is nonsense and blasphemy, but the way to become acquainted with God is through a different way of reflecting than that which journeys outwards to the beginning of time.

What is it to love life? It is to love each second of life. But what is the experience of life? It is what I do on a day to day basis. This morning, I lay in bed and at some point I chose to get up. I could have lain there a little longer. I chose to make some coffee. I could have chosen to make tea. My basic fundamental experience of life and what I love about it is my ability to choose. My basic experience just like my experience that grass is green is that I have absolute freedom of will. Of course, I may be deceived in my experience. But then again since Descartes we know that I may be deceived in my experience of the external world. The route of scepticism ends in a cul-de-sac. But my sense of freedom is as real to me as anything else in the world (if not more so). I would less readily doubt my freedom than anything else apart from my existence. I am free, therefore I am.

But my freedom is such that I am an uncaused cause. Every choice I make is uncaused apart from the fact that I choose. There is nothing or there need be nothing that compels me to choose to drink tea or coffee. I can do either. But Hawking’s universe has no uncaused cause, at least not after the Big Bang. Physics amounts to billiard balls hitting against each other. Perhaps, they are complicated little billiard balls that behave in complicated ways, but still this is all materialism, for all there is, is matter. Every action has a cause. A neuron hits against an electron, a quark flutters and I choose to drink coffee.

Science would like to explain my uncaused cause as biology. The brain is just a collection of atoms and through a complex series of reactions I choose to drink coffee. But why should I doubt the basic experience of choice for the sake of a theory about atoms and subatomic particles that I cannot see? Why should not my fundamental feeling of freedom trump whatever science tries to do in order to explain that my feeling of freedom is illusory? If science could prove to me that the world I see was in fact an illusion, I would still believe in the world. Well, by the same token, I still believe in my freedom despite whatever science can attempt to do that proves that I am really a complex automaton. I do not feel myself to be an automaton. Nor do you.

The rest follows of itself. My sense of freedom is my sense of something that is not controlled by the laws of physics. Every step I make is its own little miracle. It is an uncaused cause. It is this that makes me love life. If everything I did was caused by instinct, by need, by atoms, I would hate life and would consider it not worth living.

Alyosha is saying to Ivan ‘reflect on your own individual experience, the fact that you love life.’ “Love it before logic.” There is a mystery at the heart of life and that mystery is that we are free in a way that cannot be properly explained.

Here, again, is the key to Christian existentialism. We must go beyond logic. When Wittgenstein wrote his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, he set out the logic in pages of brilliance that staggered his examiners in Cambridge. They said they didn’t understand it, but it was clearly a work of genius, so despite there being no footnotes, he got his PhD. After the most brilliant logical demonstrations, however, Wittgenstein concluded his work in the following way:

My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognises them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them (He must so to speak throw away the ladder after he has climbed up on it.)

He must surmount these propositions; then he sees the world rightly.

Whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent. (6.54-7)

The ultimate truth of the universe is beyond logic and beyond the ability of man to understand. It can therefore only be expressed in literature in art and in music. It can, however, be experienced and, indeed, is experienced by us every day in the miracle of our freedom.

From my freedom, I know that I am not dependent on atoms and from this I know that I am something other in my essence from rocks and trees. What I am is not something I am ever going to understand for it is beyond the wit of man to explain. Hawking is trying to storm the gates of heaven with his reason and, finding nothing there, declares there is no heaven and no God. But his efforts are as vain as medieval monks who tried to come up with ingenious logical proofs of the existence of God. You cannot get there with logic, so don’t try.

If what I am is not dependent on physics, then why should my existence not survive the death of what I am physically. If truth ultimately is beyond logic, then why should not a virgin give birth, why should not God be both God and man or God and not God? Why indeed should not there be resurrection, death and not death.

We are not there yet. Alyosha tells us that Ivan’s love of life is such that he is halfway there. He still has to recognise that he has reached the top of the ladder and must then throw it away. He has to leap. As Kierkegaard taught us, he has to embrace contradiction.

Of course, once you have done that, theology and philosophy are finished, for which reason Wittgenstein recommended working on a farm. But what is left is the ability to experience God from within, from the miracle of freedom and existence, and to express this feeling in art. The greatest composer of all, I think, is Olivier Messiaen because he spent his life trying to express what was beyond the ladder and for brief moments as with, for example, his “Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps” he succeeds. We glimpse it. Or at least we can if we choose to do so.

Sources

Fyodor Dostoesvky. The Brothers Karamazov, translated by Pevear and Volokhonsky, Vintage, 1992.

Come back next week for Chapter 6: Dazzling With An Excess of Truth (A Musical Interlude).