Click here to read the introduction, and here to read the previous chapter.

Schopenhauer writes somewhere in The World as Will and Representation that music ought not to represent. It is many years ago that I read this, and I do not intend looking it up even if I had the text readily to hand. Schopenhauer is on the wrong side of the great dilemma that faces philosophy, which in the end can be understood as a simple choice: either Kierkegaard or Hegel. You can choose the Hegelian path, which ultimately resolves itself into the idea that everything is one thing, or you can choose the Kierkegaardian path that everything is indeed individual. There isn’t a third option. For Kierkegaard ,the individual is the base unit, which is not to say that there are not relations with others. There are. But it is as an individual that I relate to the other. With Hegel, on the other hand, in the end, I will be subsumed in the other, and in that way all contradictions will be resolved.

The choice can be explained in another way. Either you think the path is to lose the sense of self through chanting a mantra and through meditation (this, too, will take you on the Hegelian path to Nirvana), or you think that the self is retained, in which case you will avoid meditation as tending towards losing what is most precious.

Schopenhauer likewise thought in the end there is only one thing. He called it Will. He could just as well have called it Nirvana, or some other such word. But even if I disagreed with him on this, for a long time I agreed with him on the idea that music ought not to represent.

Many years ago in school there was a music teacher who I liked to plague. I worked hard in other subjects, so thought it reasonable to play the fool in subjects that were not examined, like music and RE. This music teacher played a piece of music and asked the class what it represented. Even then I thought this was absurd, and so said I thought the music represented a rabbit with Myxomatosis in a field of prunes. For this I was belted. But I was right. Or at least that is how I understood matters for many years. Music ought not to represent and when it does so, it is bad music. I hated when in Beethoven’s “Pastoral Symphony” there is a thunderstorm. It always struck me as ludicrous to try to emulate natural phenomena with music. Music ought to be completely abstract and express nothing, or at least nothing that can be spoken about.

But I have been on a musical journey these past few years and I have come to refine my view.

Two of the greatest thinkers of the 20th-century produced some of their most important works in similarly difficult conditions. Olivier Messiaen wrote his Quatuor pour la Fin du Temps while a prisoner of war. He wrote it for the only four instruments to hand in the camp. Likewise, Ludwig Wittgenstein while a prisoner of war wrote his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Both end up with the attempt to express the inexpressible. But Messiaen didn’t finish there. He went further, much further.

In the 1940s, Messiaen produced a number of works with religious titles such as “Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus” and “Visions de l’Amen.” But if you played someone a CD of either of these pieces without giving them the cover, I doubt anyone could guess what they represent. In that sense they remain completely abstract, though they express something about theology which cannot be thought.

But Messiaen in the 1950s goes beyond this completely. He goes all around France and eventually all around the world collecting birdsong. He notates it and then transforms this into music. Is he then representing birds in his music? In one sense he is, but once more if you played someone Messiaen’s “Catalogue d’Oiseaux,” I’m not at all sure that he would guess that it is about birds. Perhaps, he might guess, but really it has been transformed so that it doesn’t sound much like birds at all, or rather it goes beyond birdsong.

He continues in this way in the 1970s with his “Des Canyons aux Étoiles,” which purports to represent a canyon in Utah; perhaps it does, but no-one could guess where the canyon was and really the music goes so far beyond canyons that it even goes beyond the stars. And this is the point. This is what Messiaen is doing with his representing. He is transforming what he represents in such a way that he gives us a glimpse of what cannot be expressed.

Finally, with his greatest work Saint François d’Assise, Messiaen does something quite extraordinary. This I believe is the greatest opera of the 20th century, perhaps, the greatest piece of music. This incredible composer does something that ought quite literally to be impossible. He shows us Heaven.

Saint Francis meets an angel who plays music that gives a foretaste of the beyond. The music is so beautiful that Francis reflects that if he had heard just one more note, he would have died. The angel before playing the music sings to Francis the following:

God dazzles us with an excess of truth. The music brings us to God when the truth overwhelms us. If you speak to God through music, He will answer through music. Learn the joy of the blessed through the sweetness of sound and colour. And may the secrets of bliss be revealed to you. Hear this music that hangs life to the scales of heaven. Hear the music of the invisible (Act 2 tableau 5).

What does this mean? What is an excess of truth? It is the truth that is beyond our understanding. It is the truth that Christ is God and Man. These are two truths that are incompatible with each other, God and not God, Man and not Man. Likewise, the resurrected Christ is dead and not dead. It is the combination of truth that expresses opposites that is the excess of truth that dazzles us. It is contradiction. When we are sitting perplexed having failed to understand the deepest truths of theology, then we can by all means reject it as all lies and nonsense. That is the rational thing to do. That in one sense is the correct thing to do. Alternatively, we can allow the music to bring us to God. If you are open to the music that Messiaen is playing, you may just get an answer. It is only when the intellect is crushed, when doubt overwhelms us, that if we are open to it, there is the chance of glimpsing what is beyond when we climb above the ladder and throw it away. Messiaen represents birds but uses them to represent heaven. They are the rungs on the ladder that carry him higher, so that finally he reaches where they cannot even fly. So Schopenhauer is wrong, but he is also right. Music represents and does not represent.

Messiaen’s opera Saint François d’Assise has more truth in it than whole libraries of theological speculation that amount to so much very dull argument about nothing at all. It is an opera that is rarely performed, but you can see it on DVD. The experience if you are open to it is the nearest thing to heaven that can be found here on earth. Even if you are not religious, you will find expressed the inexpressible. The deepest things cannot be expressed through reason. The attempt to do so simply brings them down to a level that is human all too human. As Francis says near the end:

Music and poetry have brought me to You, in images in symbols because the truth escaped us. Lord, light me with Your presence, free me, stupefy me, blind me forever with Your excess of truth.

Music and poetry can express what is beyond the ability of reason to depict. It is in this sense that music both represents and does not represent. It represents what is beyond our words, that about which we must remain silent. Messiaen created a new language of music in order to go beyond what had hitherto been possible. This new language is difficult. Like every language it requires time and effort to learn. But to dismiss it without having taken the time to learn is like someone who has not learned Russian going up to a Russian and saying you are talking gibberish.

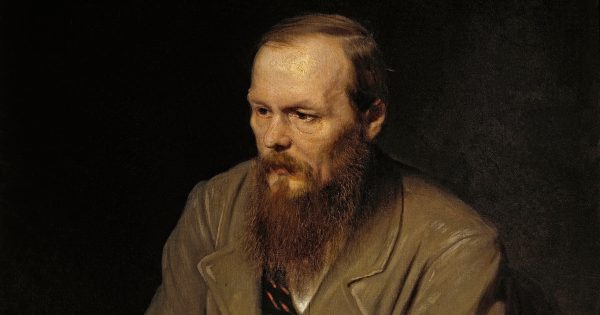

If it were up to me, if only I had the courage and the ability to sacrifice self-interest, I would take my students and give them a course in Messiaen. I would tell them to learn Russian, so they could read Dostoevsky, German so that they could read Wittgenstein, and Danish so they could read Kierkegaard. When they had made some progress in this, I would play them Saint François d’Assise and tell them to go home and do something useful with their lives, above all, be kind and try as far as they are able to follow the example of people like Francis. I would then say I have nothing more to teach, for there is nothing more to be taught.

Come back next work for Chapter 7: Martyrdom.