Click here to read the introduction, and here to read the previous section.

The Grand Inquisitor’s criticism of Jesus is that he was not political. He should have made his kingdom of this world. He should have been the Jewish Messiah seeking to overthrow the Roman Empire. But he could only have been this by giving in to the temptation of the Devil. The Inquisitor says “who shall possess mankind if not those who possess their conscience and give them their bread” (p. 258). This is the mission of the left. The party took over the conscience of each citizen and provided a cradle to grave system of giving bread. This too is the aim of all of the Left. Dissent is not tolerated. Political correctness forbids what ordinary people want to think. The bargain is that by accepting that conscience is taken over you get welfare you are looked after. This is all done moreover in order to break down the nation state. If only we could have no borders and allow anyone from anywhere to move where they wanted, we would have no countries and no distinctions between peoples. There would be no peoples, only humanity.

The Grand Inquisitor realises that the Church has not reached its goal. The people are building a Tower of Babel, but this will end in cannibalism. The Tower of Babel is the thing that created division between people, because it created the distinction of language. The aim of the Church is the opposite. It is to bring about a world without this distinction. Let us all speak Russian and then we can build socialism.

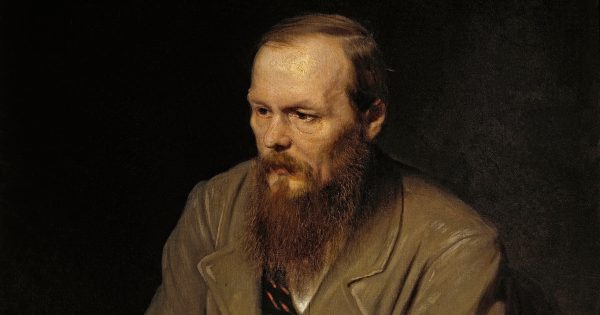

Dostoevsky is saying that these attempts to destroy individualism, the family, the nation, are the work of the Devil, or the work of his, or Ivan’s Inquisitor. But really this has less to do with Catholicism than with socialism.

The Grand Inquisitor is fundamentally arguing that what matters is pacifying humanity and taking away its freedom so that it should be content on earth. It is an anti-religious message, even though the Grand Inquisitor himself believes in Jesus. But once more this is in essence communism. It’s not religion that is the opiate of the masses but Marxism, for Marxism by attempting to bring heaven down to earth is trying to pacify humanity so that it is fully content with its lot even if it has no freedom. He argues “We shall convince them that they will only become free when they resign their freedom to us, and submit to us” (p. 258). We will force them to be free. This is how the left always distorts language. This is the Orwellian message of the Left. If you give up your freedom you will be truly free.

The Grand Inquisitor thinks that freedom leads to chaos. Given the ability to think for himself, man will revolt and exterminate each other. Finally faced with enough such horrors man will come to the Church and say “you alone possess his mystery, and we are coming back to you—save us from ourselves” (p. 258). Again Dostoevsky is pointing forward to the horrors of the twentieth century. But although he is prescient in this he is mistaken. It was totalitarianism and the loss of freedom that was responsible for the horrors of Communism, Nazism and Islamic fundamentalism. Each of these tries to limit man’s freedom. No truly free society, which valued individualism, was responsible for these horrors.

The Grand Inquisitor thinks that happiness consists in submitting to authority. But again twentieth century history suggests the reverse. How much long term happiness did the authority of communism and Nazism give to the people living under these regimes? Would you have preferred to live in Germany, the Soviet Union, or the USA in 1939?

The Grand Inquisitor wants people to be like children, not proud but pitiful. He thinks this will make them happy. But it is really the old dilemma, “would you rather be a pig happy or Socrates unhappy?” Once more, it is the idea of taking away responsibility, cradle to grave welfare. But this is to be a pig happy. But it doesn’t even work for all the pigs. Eventually a pig will decide that it is Socrates and that it wants to choose for itself.

The Grand Inquisitor describes the essence of Communism when he says that the people “will tremble limply before our wrath, their minds will grow timid … but just as readily at a gesture from us they will pass over to gaiety and laughter” (p.259). Think of the crowds in North Korea. Think of May Day celebrations in the Soviet Union. We have all seen the crowds of happy people who have been commanded to be happy. No-one was commanding the people in Seville in this way when the Grand Inquisitor lived.

The Grand Inquisitor will arrange leisure time like a children’s game, with songs and innocent dancing. This sounds just like the House of Culture in every Russian town. Moreover he “will allow them to sin, too; they are weak and powerless, and they will love us like children for allowing them to sin” (p. 259). This too looks forward to some Soviet ideas of free love where experiments were made with breaking down the ideas of family and marriage. But it also looks forward to the free love of the 1960s and beyond, where in the West the idea that there is such a sin has been undermined.

Again the Grand Inquisitor thinks that if only he can take away man’s freedom he will be content. He says that “they will have no secrets from us” (p. 259). This indeed was the experience of communism in the Soviet Union. A network of spies reaching even into the family meant that there were no secrets. A chance remark whispered to a stranger might come back to you.

The Grand Inquisitor describes a society where the elite, people like him have freedom and knowledge “There will be thousands of millions of happy babes, and a hundred thousand sufferers who have taken upon themselves the curse of the knowledge of good and evil” (p. 259). Only the elite rulers will be fully human then, the rest will be as it were living in the Garden of Eden. The elite will promise these people a heaven on earth and heaven in heaven, but they will lie about the latter. The Inquisitor does not think there will be an afterlife for them “Peacefully they will die, peacefully the will expire in your name, and beyond the grave they will find only death” (p. 259).

But why should this be so, for the masses have no sin. If they are in the situation before the Fall of man, before there is any knowledge of good and evil, then these masses are in the situation of infants. Their situation is even better than that of infants because they have no original sin. Why should they not then be saved?

Sources

Fyodor Dostoevsky. The Brothers Karamazov, translated by Pevear and Volokhonsky, Vintage, 1992.

Come back soon for Part 6 of Chapter 10: Grand Inquisitor.