I was a rather serious, odd little child. I had a deep alertness when it came to my own conscience, which manifested in facial expressions I could never really manage to hide. So, when my young mother sat me down one day on the cold, tile floor of our base-housing residence, I’m sure that the face of this four-year-old, already bespeaking guilt in its somberness, somehow grew only more somber.

In short, she recalled the whole Gospel in unadulterated detail. She was never the type to candy-coat. And, after weeks of a troubled spirit regarding specific sins I had already accepted as wrong, the news was painfully welcome: Christ took the punishment that I deserved. The thoughts of His torture sickened my stomach and prompted uncontrolled tears.

“Never forget, Whitney Ann—it took no more of Christ’s precious Blood to cover you than anyone else.”

Now, lest you get the idea that I was a toddler-axe murderer—of course, I was not. I had managed to steal a book (a particular weakness from the start) and place it under my bloomered-bottom while hitching a ride via my stroller. However, the very act of hiding the object proved that knowledge so woefully gained in the Garden.

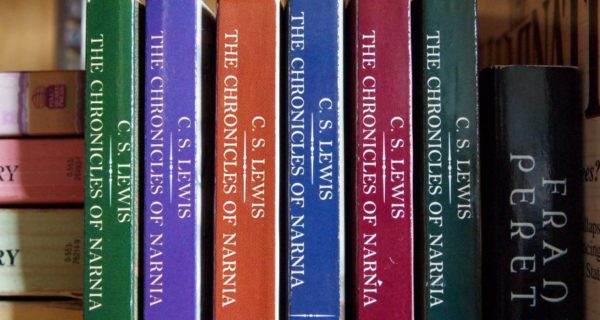

C. S. Lewis reminds us in wisdom that the path to Hell is a gradual one. One may be as tempted by a “deck of cards” as by the lustful treachery of murder. The means is merely a vehicle, a manifestation, of the heart’s problematic appetite:

“It does not matter how small the sins are provided that their cumulative effect is to edge the man away from the Light and out into the Nothing. Murder is no better than cards if cards can do the trick. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one–the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts” (Screwtape Letters).

Lewis had a wonderful way of reminding us that the condition of humanity is universal—as is its solution, thankfully.

The Pharisees, it seems, could not comprehend this message, despite the fact that it intertwined every one of Jesus’ messages. To them, righteousness was a rather simple “game” of boundaries. So long as one didn’t cross those boundaries—however close they managed to get didn’t matter—one was “safe” in the eyes of God. Jesus masterfully exposed this facade by directing them to the matter of the mind.

The heart’s walls are, after all, where every sin begins. In His Sermon on the Mount, Jesus equated, with silencing clarity, “undue anger” with “murder,” and “lust” with “adultery.” Indeed, these truths effectively roused the people to a degree of anger which only reinforced the fact that He had spoken a cutting and uncomfortable truth.

As an introvert, the battle of the mind has always been a very real one. I tend to overthink matters. And, as always, Satan has a way of turning every virtue into a vice. Elsewhere, we are commanded to love Christ with all of our “minds.” Prior to salvation, our minds are bent towards self-absorption, and even following peace with Christ, the battle between the flesh and spiritual mind rages.

The Greek word for “mind” as used in Matthew 22:37 denotes the “feeling, desires, understandings, and imagination” of man. In short, loving Him with our minds involves deliberate meditation and adoration of His work, person, and character. It refutes the Adamic, sneaking suspicion that God ever withholds His goodness, and instead embraces a childlike trust in His revealed will.

The fact is, sin is as much a state of being as it is an action; Adam’s sin bled through every vein of humanity—so much so that the earth continues to anticipate a holistic healing (John 3:17).

As I grew older and the process of His sanctification grew with me, I realized that sin has both an active and passive voice; that to omit obedience is equal in “sinfulness” to blatant disobedience. Consequently, my understanding, appreciation, and adoration for what Christ did at the Cross magnified.

Christ came not only to deliver us from sin, but to heal, restore, and make us whole. This is the consummate plan of redemption. Lewis describes this delectable vision, when “all things” will be made right:

“Wrong will be right, when Aslan comes in sight,

At the sound of his roar, sorrows will be no more,

When he bares his teeth, winter meets its death,

And when he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again.”