I discovered this one windy December day when a friend called and insisted that I go see the annual Christmas display at Lyndhurst, the historic mansion overlooking the Hudson River in Tarrytown, New York. Because people’s self-consciousness about public Christmas displays is so overwhelming these days, it’s getting harder to find an elaborate one anywhere. I considered it almost a religious duty to go.

Built in the style of a medieval castle or cathedral, Lyndhurst was designed by Alexander Jackson Davis, the leading American architect of his day. Lyndhurst is considered one of our finest examples of Romantic architecture, built in 1838—when the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen were hard at work, selling millions of copies of their stories about princesses, witches, magic spells, and gingerbread.

The exhibit’s decorator had transformed room after room into different fantasies, each based on a classic fairy tale. Snow White’s room had a tree covered with red apples, a floor mounded with drifts of cotton snow, and seven sets of dwarf hats and boots hanging from the mantle. In a different room, there was a twelve-foot-high “Cinderella” tree decorated in shades of blue with little shoes all over it. In the Little Mermaid’s room (the bathroom), glass bubbles were spilling out of the bathtub and little fish hung in mid-air, seeming to drift slowly with the currents. I was charmed, and found myself saying aloud that the exhibit ought to be the subject of a book, which I promptly began to write.

I hadn’t thought too much about what these fairy tales really had to do with Christmas, but I knew there was a reason why Christmastime is when The Nutcracker is danced and magic is so effortlessly embraced. It all seems as appropriate as baking cookies. But in addition to the scholars who like fairy tales for all the wrong reasons, I have also met serious Christians who think that the magic is a cheap substitute for real faith and don’t trust the stories at all.

I had no idea where the search would end, but I had to begin by reading the tales. It must have been in the middle of the night when it dawned on me that it was a remarkable coincidence that Snow White dies because she disobeys a warning and eats an apple. It reminded me of a woman in Genesis who found herself in a similar predicament. About the same time, I started reading “The Little Mermaid.”

In a wonderful twist at the beginning of the story, the Little Mermaid sees our human world as the fairy-tale one—beautiful, exotic, and magical. Andersen describes it so wonderfully that we can see it that way, too, through the eyes of a simpler, less-human creature.

I knew, or thought I knew, that in the original story, the Little Mermaid doesn’t live “happily ever after.” (Unlike Cinderella, she loses the prince after all her trials.) So I read it expecting a sentimentally tragic ending. Instead, I found that she refuses to commit a treacherous murder even at the cost of her own life, and because of this, she’s rewarded with a soul and eternal life. Though she fails in her temporal goal, she finds eternal happiness by persevering in goodness, and the world is blessed by her salvation. How unexpectedly Catholic, I thought—an analogy to the triumph of the Cross.

Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875), who wrote the tale, was a notorious wit and lethal satirist, best known for stories like “The Ugly Duckling” and “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” His outspoken belief in God’s mercy and the goodness of creation is often invisible today when his stories are carelessly abridged.

A contemporary of the Grimms and Dickens, Andersen was writing when the atrocities of the Age of Reason were still in living memory. Like the works of the Brothers Grimm, his periodic collections were always released just before Christmas and were instantly and wildly popular. These writers were a part of the Romantic movement, which was in part a cultural war against the godless, abstract ideologies of the French Revolution that had occupied European thought since the 1790s. The Romantics gave voice to a renewed interest in religion and folk culture, which emphasized the mystical, intuitive, and physical aspects of human nature.

Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” begins with a sub-plot about a mirror made by a demon. When viewed by reflection in the mirror, all good things seem distorted and shrunken, and all bad things look bigger and worse than ever. Men look “as if they stood on their heads and had no bodies,” according to the tale. This was precisely the problem with French rationalism: It was a pathetic attempt to make mankind fit a theory, instead of the other way around. The rationalists did not accept the reality, frailty, and necessity of the human body. They did away with a midday meal so that the population could be forced to attend long political meetings. They decreed that people and animals must work a 10-day work week (both rebelled), and made nativity scenes illegal. Andersen had a good grasp of John Paul II’s theology of the body a century-and-a-half early.

The story continues as the demons attempt to fly to heaven to try the mirror on the angels. But the higher they go, the more hideously it grins and shivers, until it crashes to the ground and shatters into a million pieces. Splinters from the mirror land in the eye and heart of a young boy named Kay. Suddenly he begins to see only imperfection around him, and he makes fun of everything, including his faithful little playmate, Gerda. Kay is lured by the Snow Queen to the frozen north where, all alone and freezing to death, he amuses himself by playing with identical puzzle pieces of ice on the vast, frozen lake called the Mirror of Reason.

The Snow Queen leaves Kay alone, telling him that he will be his own master and have his freedom only if he can spell one word: ETERNITY. But for all his cleverness, Kay cannot spell it, and so he is trapped. Gerda makes her way to him in the Snow Queen’s palace, weeps, and sings a hymn to the Christ Child. The icy puzzle pieces dance and form the word ETERNITY by themselves, and the shards of mirror are washed from his eye and heart by tears—Gerda’s and his own. In other words, the answer to the ills of the world is not in destroying everything that is imperfect, but in recognizing the incarnate Christ Child.

“Snow White” was first published in 1812 by the Brothers Grimm—Jakob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859)— in a collection called Kinder- and Hausmarchen (Children’s and Household Tales). “Snow White” is a straightforward story about the Fall and Redemption—a kind of Paradise Lost for the common man. Besides the deadly apple, there’s the evil queen, who is the most beautiful in the land until Snow White comes along. She’s much like Milton’s Lucifer, the greatest of the angels, who rebels when God creates mankind.

If that weren’t obvious enough, Snow White is brought back to life by a king’s son who declares that he loves her more than anything in the world. He takes her to “his father’s house,” and there is a great wedding feast. The biblical allusions run throughout the story:

The poor child was now all alone in the great forest, and she was so afraid that she just looked at all the leaves on the trees and did not know what to do. Then she began to run. She ran over sharp stones and through thorns …

Thorns and thistles shall it bring forth to thee . . . till thou return to the earth out of which thou toast taken (Gn 3:18).

Snow White longed for the beautiful apple, and when she saw that the peasant woman was eating part of it, she could no longer resist.

… and she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat (Gn 3:6).

The prince had his servants carry [the coffin] away on their shoulders.

And they forced one . . . who passed by … to take up his cross (Mk 15:21).

Not long afterward she opened her eyes, lifted the lid from her coffin, sat up, and was alive again.

And taking the damsel by the hand, he saith to her: Talitha cumi, which is, being interpreted: Damsel, I say to thee, arise (Mk 5:41).

“Come with me to my father’s castle.”

This day thou shalt be with me in paradise (Lk 23:43).

It may not come as a surprise that Wilhelm Grimm read his New Testament in Greek every morning, underlining profusely, as Rev. G. Ronald Murphy relates in his book on the Grimms and their faith, The Owl, the Raven, and the Dove (Oxford University Press, 2000).

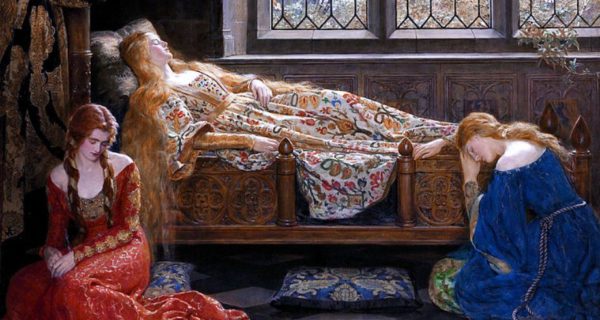

“S. Lewis thought that “Sleeping Beauty” was also about our redemption. Using different images, it seems to have a similar storyline: A girl is punished for her parents’ transgression; the punishment is not taken away but altered from death to sleep, and again a prince comes to wake her. Only one prince can free her, though many make the attempt. Thorns—like those that crowned Christ—grow up from the ground outside paradise, and thorns grow to obscure the tower where she sleeps.”

Perhaps the strangest Grimm tale is “Hansel and Gretel,” which seems to be about the passage from the pagan world to the Christian one. It begins with a temptation universal to human nature: trying to save one’s own life by depriving someone else of his.

The children’s father is torn with anxiety over his growing poverty—and his concern seems untempered by fear of the Lord. His wife is a cold rationalist—untempered by wisdom or virtue. With mathematical precision, she suggests that having two out of the four family members survive is better than none surviving, therefore, they should abandon Hansel and Gretel in the woods. The father is horrified, and notices she is not offering to sacrifice herself.

But since the father is trapped by his fear and doesn’t have a better solution, he goes along with the plan. He even puts his talent to use by tying a dead branch to a tree to imitate the sound of his axe chopping wood—falsely reassuring the children that he is nearby while he and his wife make their escape. The dead branch could be seen as an allusion to the dead wood that bears no fruit (Jn 15:6)—the emptiness of philosophies and religions that sound reassuring, but ultimately abandon mankind.

In contrast, Hansel repeatedly reassures Gretel that “God will take care of us.” He has obviously inherited his father’s resourcefulness and takes very specific action. He engineers their first escape by filling his pockets with white stones that shine in the moonlight “like new-minted coins.” My mind goes immediately to the Eucharist, which is displayed for adoration in a container called a luna, Latin for “moon.” It is also possible that the stones represent those that David collected on the way to his appointment with Goliath. The allusion to the Eucharist is reinforced the second time the children are marooned, when Hansel leaves crumbs of bread to guide them.

After being presumed dead for three days, the children are greeted by a white bird with a beautiful song, which leads them on to the witch’s house. The bird suggests the Holy Ghost—but why would He lead them into a trap? It becomes apparent that with their wisdom and faithfulness, the witch’s house is no trap for them, any more than the hostile land of Canaan was for the Israelites. Hansel and Gretel have been chosen to discover the treasure of Christianity, vanquish the witch representing paganism, and redeem their household.

The children eat a meal of pancakes—like the one traditionally served on Shrove Tuesday before the fasting of Lent begins. Hansel is then put into a prison, while Gretel is fed a thoroughly Lenten diet of crab shells. Hansel has given the example of fidelity and resourcefulness. Now alone, Gretel uses her own wits and resolve to trick the witch into poking her head into the oven—whereupon Gretel gives her a hearty shove and locks the oven door behind her.

In the Grimms’ tale, the witch’s house is called a “house of bread.” Anyone with a smattering of Hebrew will recog nize that phrase as the translation of “Bethlehem.” It is also the city of David and the later birthplace of Him whom we call the “Bread of Life.”

Inside the witch’s house are pearls and precious stones—as in the “pearl of great price” that, in Our Lord’s parable, refers to the treasure of faith. The children fill their pockets and, like the Magi, return home by a different route—one that requires them to cross a large lake. Even Bruno Bettelheim, who had many grisly and improbable theories about this fairy tale, suggests that the lake represents some kind of baptism. A white duck is there to bring them across, but Gretel observes that the duck is only big enough to hold one of them at a time. As with the journey toward God, it’s a voyage each must take alone.

Arriving home, Hansel and Gretel embrace their father—his wife is not there, because she is now dead. They give him the jewels they’ve discovered in the “house of bread,” and the three live in perfect happiness, never again suffering anxiety.

The original Nutcracker story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776-1822), is about a young man who frees a princess from a curse brought on by her parents, which has rendered her hopelessly ugly. She has promised to marry him for his effort. But as he frees her, his face takes on her ugliness and she rejects him. Hearing the story, Drosselmeyer’s goddaughter is grieved by the ingratitude of the princess. When she promises to marry him in spite of his ugliness, he turns back into a handsome youth, in a scene that almost exactly parallels one from “Beauty and the Beast.”

Though the story is rather haphazard, it does clear up the little mystery of why the Nutcracker has a funny-looking face. It also contains one or two more details: In order to undo the curse that the Nutcracker has selflessly taken on himself, the Mouse King must be defeated. Incidentally, the Mouse King has seven heads, like the dragon of the Apocalypse. And in Hoffmann’s original story, the young girl’s name happens to be Marie.

No coincidence there.

~~~

This article was Originally published on Crisis Magazine