One of the objections that has been raised frequently against the Christian concept of redemption through the cross, is that God would not require a blood sacrifice in order to forgive sins, nor indeed that God would not require a sin (i.e. the unjust condemnation and execution of Christ) to forgive our sins. This is especially common within Muslim circles. I feel that this objection mainly targets simplistic theological explanations on the part of some Christians, and which requires multi-faceted analysis.

People often parrot “Jesus died for you!” but even trying to explain how all that works on a theological level. Even reading through scripture off the cuff, without substantial secondary sources, as well as cultural and historical context, will leave one more potentially perplexed than enlightened. Both the Gospels and Epistles, for example, makes copious use of Jewish allusions to Passover Lambs and “Scape Goats”, sacrifices which were made on behalf of the people of Israel in reparation for their sins. This in turn opened a floodgate of atonement theories which can often be skewed to make God seem like a blood-thirsty deity demanding violence before He can forgive.

And yet, in spite of some of these hit or miss constructions, it strikes me a strange, marvelous thing that, even on a bare-bones level the notion of “the death of God” – the ultimate evil and emptiness that can be conceived of – is in turn seen as a source of salvation as opposed to the undoing of creation. It is not the sin of those who betrayed and killed Christ that proves redemptive, but rather the willingness of Christ, in perfect obedience and submission to the divine will, to bear the weight of it, be crushed by it, and yet to rise again having paid the full consequences that sin naturally entails.

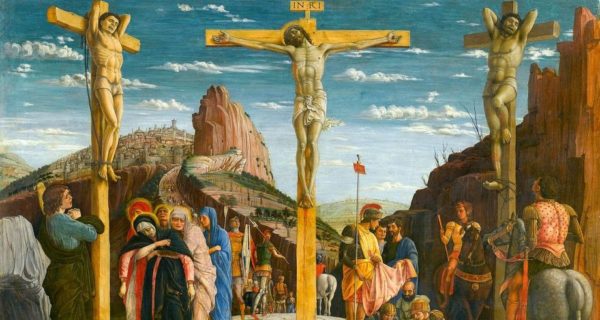

All iniquity brings its own punishment… yet Christ stands in the gap, and takes it into Himself through self-sacrifice. God doesn’t simply speak it away, but subsumes it within Himself. Sin itself killed Christ, represented by the dysfunction of all those who took part in the Passion drama, from those who conspired against Him, to the one who betrayed him, to the one who denied Him, to the one who condemned Him, to those who chanted for His death in the courtyard, to those who beat Him, and spat in His face, crowned Him with thorns, and nailed His hands and feet, mocked him under the cross, and thrust a lance into His side, from whence blood and water flowed.

And… He forgave them.

“Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

All sin, in a sense, “wounds” God, causes rifts in our relationship with Him. We pierce Him through the heart, and each other through our hearts, constantly. It has real consequences, and real restitution must be made before reconciliation can take place. But how can we, on our own, ever hope to bind the wounds we inflict upon God? Can our inherent imperfection ever reach the heights of perfection necessary to enter into that torn heart and sew it up? No, only the intervention of God Himself can do that, and He shows us how, by pouring Himself out, and binding Himself up, for us. God and Man are restored to friendship through both natures mingling, dying, and rising again.

At the crucifixion, we see the cosmic become personal, acted out in real time and space in the person of Christ, being wounded and rent, as we wound and rent one another every day. The entire history of Mankind is fused into this moment, as if the impact of sin is carried to its end conclusion, and the entire weight of it is borne down upon the God-Man. We wound God, but that seems very far away from us. We wound Christ in His humanity, and we see forever the marks upon His body, even after His resurrection. It is terribly real to us, this bringing of heaven down to earth, this true damage that sin wreaks, for what we do to the least of us, we do to Christ, our brother, as well.

I think a key point to bring up here is that while both Muslims and Christians all agree that God forgives sins, Muslims view them solely as an individual matter, while Christians view them both individually and cosmically as a twisted condition which all humanity labors under. Hence, yes, God can forgive sins on a personal level (and I believe He has and does, towards any with a sincere desire for forgiveness), but He deals with mending the brokenness of the condition through cosmic means. And that cosmic means, to me, is the secret of the whole universe: Sacrificial Love, which God unfolds for our redemption by unfolding His agony.

Using Jewish paschal language, Christ is the Lamb of God, a fulfillment and finality of sacrifices made according to the Old Covenant, whose life-blood cleanses away sin by enduring the weight of its consequence and transforming it to glory. The Lamb is part of God’s very self, indeed the Lamb slain since the very foundation of the world, yet also part of the mess of Mankind. He can represent us as much as He can represent God, by living a truly human life and dying a truly human death, and so He can make us a new creation, and repair the cracked shell of the egg of the world, even as He is cracked, and His life-blood spills out, like new wine bursting out of old skins.

This sacrifice of Christ digs down to the root of ancient banishment from God’s presence, and harrows them up in a way no other act of reparation could complete on its own. Such sacrifices in the past were small glimmerings of the great necessity of making amends and atonement, that people of various cultures and eras foresaw in their own sin offerings. However, such sacrifices were always understood as being solely *to* the divine, as opposed to the divine being the sacrifice Himself on our behalf. Christianity turns this on its head, and gives us a “blood transfusion” from God to make us one with Him.

Christ outstretched upon the tree, laying aside all His miraculous potential, in utter resignation, is like throwing ice into a bowl of hot soup. The One who had the power to raise the dead to life and command the elements to obey and speak with authority beyond the Torah, has now become utterly and completely helpless. This willing victim to the ravages of sin shatters something in the cosmos, a barrier between God and Man, just as the Curtain Temple in the Holy of Holies splits, as Christ’s heart is pierced. The power is knit into the paradox, of the divine life taking flesh, and that flesh getting torn up by the jagged edges of this world.

It is like the images from Narnia, of the ice cracking to herald the spring as Aslan’s camp draws near, or even more memorably, the stone table cracking down the center, so that, in accordance with the ancient magic, an innocent victim at the hands of evil might pardon the guilty betrayers. It’s what C.S. Lewis likened to diving into an ocean to retrieve a treasure from the sand. Christ descends to the darkest point willingly, and rises to the surface again glorified, pulling us up with Him in that glory. We are transfigured as the very Body of Christ. As He is elevated, so we are elevated.

Could God have just forgiven us on a cosmic level without Christ dying on the cross? God can do as He wills, but this we believe is exactly what God willed, so it’s a bit of a moot point. But again, there’s more to it than that. Our human condition, dysfunctional as it is, needed to be more than simply “forgiven”, but also transformed, and only through God’s wedding heaven to earth in Jesus Christ, being conquered by death so He could in turn conquer death, is this brought to fruition. Hence, it was the very perfect way to enact this cosmic forgiveness and invitation to become not just servants, but Children of God.

The image of the cross represents a hot cloth that draws out infection, like the bronze serpent raised in the desert for the Israelites. It is why Christians down through the ages have cried, “Behold the Cross, on which hung the salvation of the world!” It is why Christian martyrs have died for it, and the belief that Christ rose from the death sin had consigned Him to suffer, and they were willing to unite their sacrifices to that cosmic sacrifice that God makes when He condescends to empty Himself so that we might be drawn into His bleeding heart.

And what is salvation, you might ask? It is nothing more or less than sharing in the fullness of the divine life. This is also the nature of heaven, which is not so much a place, as a state of being in union with God’s interior workings, being adopted into the divine family and reborn on a supernatural level. This, in the sacramental life, is initiated through the waters of Baptism, when we reenact “dying” and “rising” with Christ, in Him and through Him. This is also an extension of the Trinitarian mystery, which is ever-dynamic, pulling people into its spinning center.

To quote Raja Selvam: “Through his forgiving and suffering love, specifically by his divine will of reconciliation, this divine embrace has become proximate to every human life. Therefore, forever into God human being has been taken up and forever into human being divine being has entered. In other words, there is a total penetration, a full mutuality, and a total possibility of a complete relationship. That is, Creator and creatures are reconciled, but more than reconciled. They can now be joined in a way that was never before possible.”

On a personal note, the cross has always been the most compelling aspect of the faith for me, because it was something which one could never “lose” through suffering or spiritual abandonment. It is always there, a beacon of passion, of arms outstretched in pain and love for us, even as we pierce Him through. It is inside of me when all other lights go out. It is the key that unlocks meaning of life for me, and which I believe tunnels through the darkest depths of sin, and emerges on the other side victorious.

When I go into a room, it is the first thing I search for; when I enter Church, it is the first thing my eyes focus on above the altar. If I see it etched in a wall, I’ll trace it with my finger. When I was young, my dad would ask why I kept looking over my shoulder in the living room, and I said it was because the cross was hanging there, and I couldn’t forget it. I gaze on it still, with my eyes, or in my heart.

Amen. Well said. Thank you.