Everyone loves Christmas. It’s a time for gifts, singing, merrymaking and feasting. It is a time for family, friends and community. The central focus of the festival is of course the commemoration of the birth of Jesus, celebrated on the 25th of December. It is a tradition that has been borrowed, rather than invented, by the Christian faith and is still celebrated by Christians and non-Christians alike today. Whilst singing Adeste Fidelis by candle-light at midnight mass, one could almost imagine what our medieval ancestors may have experienced. We all know that many Christmas traditions actually have their origin in Victorian times or even later. But what was it like for people in medieval England long before the advent of Christmas trees, stockings, Santa Claus and expensive presents? Of course, Santa Claus was in reality a monk called Nicholas born around 280 AD near modern day Myra in Turkey. He became known as a protector of children hence his connection with presents for them, but he is associated with the twentieth century for the most part. Winter festivals have been a popular fixture of many northern European cultures throughout the centuries. A celebration in expectation of better weather and longer days as spring approached, coupled with more time to actually celebrate and take stock of the year because there was less agricultural work to be completed in the winter months, has made this time of year a popular party season for centuries.

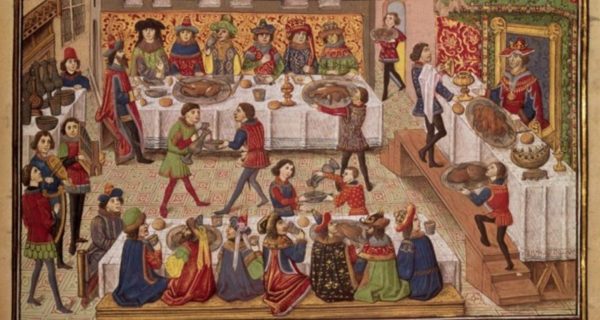

We sometimes romantically think that medieval Christmas must have been filled with royal banquets in green-decked halls, with minstrels singing songs of festivities, with royal personages, nobles, lords and ladies dancing with glee. On the contrary, if we go back far enough, Christmas itself was not a time of fun and merriment, it gradually developed as a time of great merrymaking and jollity as the Middle Ages went on. England at that time was very much a Catholic country and a proud member of the wider Christendom in communion with the Pope in Rome. The word Christmas was derived from Cristemasse, a Middle English name for the festival. Before this it was known as Yule or Mid-Winter by our Anglo-Saxon ancestors. The Welsh name for the festival is Nadolig, which comes from the original Brythonic tongue spoken in this country long ago. Crist was from the Greek Khristos which means anointed. Whilst the term ‘Christmas’ first became part of the English language in the 11th century as an amalgamation of the Old English expression Christes-Maesse, meaning festival or mass of Christ, the influences for this winter celebration go back into the mists of time. Our Norman over-lords in the Middle Ages would have referred to the festival as Noel, from the Norman French referring to the birth of the Saviour.

The Roman celebration of Saturnalia, in honour of Saturn the harvest god, and the Scandinavian festival of Yule and other pagan festivals centred on the winter solstice were celebrated on or around this date. As Northern Europe was the last part of the continent to embrace Christianity, the pagan traditions of old had a big influence on the Christian celebrations. The official date of the birth of Christ is notably absent from the Holy Bible and has always been hotly contested ever since. Following the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire in the latter part of the fourth century, it was Pope Julius I who eventually settled on 25th December. Whilst this would appear to be in agreement with what the third century historian Sextus Julius Africanus had said that Jesus was conceived on the spring equinox of 25th March, the choice has also been seen as an effort to apparently Christianise the pagan winter festivals that also fell on this date. Early Christian writers suggested that the date of the solstice was chosen for the Christmas celebrations because this is the day that the sun reversed the direction of its cycle from south to north, connecting the birth of Jesus to the ‘rebirth’ of the sun. This, however, is not certain. The medieval calendar was dominated by Christmas events starting forty days prior to Christmas Day, the period we now know as Advent, from the Latin word adventus, meaning the coming, but which was originally known as the forty days of St. Martin because it began on 11 November, the feast day of St Martin of Tours, a very important medieval saint.

In England in the early Middle Ages, Christmas itself was not as popular as Epiphany on 6th January which celebrates the visit from the three kings or wise men or Magi, to the baby Jesus bearing gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. Almost everyone went to mass and other church services on high days and holydays. Indeed, Christmas was not originally seen as a time for fun and frolics but an opportunity for quiet prayer and reflection during a special mass. But by about the 1300s, Christmas had become the most prominent religious celebration in England, signalling the beginning of Christmastide, or the Twelve Days of Christmas as they are more commonly known today. It followed forty days of fasting after the 11th of November, St Martin’s Day. The word ‘tide’ was used originally to denote hours, the passage of time or a festival. We still use the terms Eastertide, Passiontide, and of course the tide on the beach. Festivals and holy days (which is the origin of our word holiday) were, during the medieval period, determined by the Church either centrally by Rome or locally by bishops and archbishops. As you can imagine, Christmas in medieval England was very different to modern day Christmas. It was the church that ensured that it was celebrated as a true religious holiday instead of just being a simple feast for peasants to enjoy themselves. It was, inevitably given the central role of the Catholic church in medieval England, very much controlled and defined by church authorities.

Food is a very important part in any festival. This has always been the case in Jewish festivals such as Pesach and it is also true in the case of Christmas for Christians and non-Christians alike. It is not surprising that for a largely rural population who mainly lived off the land, food was a major part of a medieval Christmas. The holiday came during a period after the crops had been harvested and there would be little to do on a farm. If animals were not to be kept over the winter, now would also be a good time for them to be slaughtered for their food. This could leave a bounty of food that would make Christmas the perfect time to hold a feast. Medieval Christmas food was varied depending on what the people could afford. For rich people, they would have prepared exotic foods such as goose and swan for Christmas. Sometimes, they also cooked woodcock. Medieval cooks prepared roasted birds for Christmas. Sometimes, they covered them with butter and saffron, and served them with a golden colour. Meanwhile, the poor normally could not afford to have such lavish preparations for Christmas. If they could, the church would sell a regular cooked goose, while uncooked ones might be cheaper. King John held a Christmas feast in 1213, and royal administrative records show that he was ordering large amounts of food. One order included 24 hogsheads of wine, 200 head of pork, 1,000 hens, 500 lbs of wax, 50 lbs of pepper, 2 lbs of saffron, 100 lbs of almonds, along other spices, napkins and linen. Christmas had become a time of excess dominated by a great feast, gifts for rich and poor and general indulgence in eating, drinking, dancing and singing.

Even at a slightly lower level of wealth the Christmas meal was still elaborate. Richard of Swinfield, Bishop of Hereford, invited 41 guests to his Christmas feast in 1289. Over the three meals that were held that day, the guests ate two carcasses and three-quarters of beef, two calves, four does, four pigs, sixty fowls, eight partridges, two geese, along with bread and cheese. No one kept track of how much beer was drank, but the guests managed to consume 40 gallons of red wine and another four gallons of white wine. Feasts were also held among the peasants, and manorial customs sometimes revealed that the local lord would supply the people with special food for Christmas. For example, in the 13th century a shepherd on a manor in Somerset was entitled to a loaf of bread and a dish of meat on Christmas Eve, while his dog would get a loaf on Christmas Day. Another three tenants on the same manor would share two loaves of bread, a mess of beef and of bacon with mustard, one chicken, cheese, fuel for cooking and as much beer as they could drink during the day.

Mince pies were also common in the medieval era. As the name suggests, they were baked and filled with different kinds of shredded meat, fruits and spices. It was only as recently as the Victorian era that the recipe was amended to include only spices and fruit. The pies were originally baked in rectangular cases to represent the infant Jesus’ crib and the addition of cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg, which were long a ago costly ingredients, was intended to symbolise the gifts bestowed by the three wise men or “Magi”. Similar to the modern mince pies we see today, these pies were not very big, and it was widely believed in medieval England, to be lucky to eat one mince pie on each of the twelve days of Christmas.

They also had Christmas puddings called furmenty or figgy pudding, which was considered a real treat for the not so rich people. They began as a kind of thick porridge or pottage with currants, dried fruits and eggs. Some had spices added to them, such as cinnamon. It might be served as a fasting meal in preparation for Christmas and originates in the fourteenth century. The word plum was often used to describe any dried fruit. Sometimes, beef and mutton as well as raisons and prunes, wine and spices could be added as a preservative. When grains were added to make it into a kind of porridge it was known as frumenty. In the early fifteenth century, it became known as plum pottage and could be packed into animal stomachs and intestines like a sausage. It kept well over a prolonged period. By the end of the sixteenth century when fruit became more readily available, it morphed from a savoury to a sweet dish eaten after the meat course.

While the most popular choice for Christmas dinner today is undoubtedly turkey, the bird was not introduced to Europe until after the discovery of the Americas, its natural home in the sixteenth century. It is believed by some people that East Yorkshire man William Strickland, acquired six turkeys by trading with native Americans on an early voyage around 1526. He is said to have sold them at Bristol market for tuppence each. He certainly made money from the trade which enabled him to buy a manor house near Bridlington where his descendent still live today. Sadly, there is no real evidence for this story, so it is unclear from sources how the turkey got to England. In medieval times though the goose was the most common option. Venison was also a popular alternative in medieval Christmas celebrations, although hunting in Royal or other forests was strictly controlled and the poor were not allowed to eat the best cuts of meat. However, the Christmas spirit might entice a Lord to donate the unwanted parts of the family’s Christmas deer, the offal, which was known as the umbles. To make the meat go further it was often mixed with other ingredients to make a pie, in this case the poor would be eating umble pie, an expression we now use today to describe someone who has fallen from a proud state to one of more modest one.

Christmas then was very different from the modern way Christmas is celebrated. Nevertheless, Christmas time in the Middle Ages still involved children. December 28th was called Childermass Day or more commonly known as Holy Innocents Day. This was when King Herod ordered that all children under two years old must be killed. The Christmas crib originated in 1223 in medieval Italy when Saint Francis of Assisi explained the Christmas Nativity story to local people using a crib to symbolise the birth of Jesus and has been popular ever since. The day after Christmas day is known as St Stephen’s Day. He was the first Christian martyr. This day, later known in England as Boxing Day, has traditionally been seen as the reversal of fortunes, where the rich provide gifts for the poor. In medieval times, the gift was generally money and it was provided in a hollow clay pot with a slit in the top which had to be smashed for the money to be taken out. These small clay pots were nicknamed “piggies” and thus became the first version of the piggy banks we use today. Unfortunately for tenant farmers, Christmas Day was also traditionally one of the quarter days, one of the four days in the financial year on which payments such as ground rents were due, meaning many poor tenants had to pay their rent on Christmas Day. St Stephen’s Day was a day of fun, jolity and reversal of roles and could however, be less controlled than the authorities wanted: in 1523 at London’s Inns of Court, a ‘lord of misrule’ was responsible for an accidental death.

Some of us enjoy the sound of carollers on our doorsteps but the tradition for carol singers going door to door is actually a result of carols being banned in churches in medieval times. Many carollers took the word carol, which might mean to sing and dance in a circle, which meant that the more serious Christmas masses were being ruined and so the Church decided to send the carol singers outside. Mumming was an ancient pagan tradition. During the medieval era, it was a diversion in disguise. Men and women swapped clothes and don masks while visiting their neighbours. They would dance, sing and sometimes act out plays with hilarious and silly plots all for the fun of the celebration.

So, Christmas as we know it today is a very different experience to that which our ancestors knew and loved. There’s was a simple affair of eating, drinking, attending church and having fun. Perhaps we have lost some of that simple, innocent pleasure and filled our festival with things rather than people. After all, Christmas is about family, friends, and community. Our medieval Catholic ancestors got it right.

References

https://www.medievalists.net/2010/12/christmas-in-the-middle-ages/

https://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/press/for-journalists/richard-iii/old-content/features/a-medieval-christmas

https://msrg.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/2018/01/12/medieval-christmas/

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/A-Medieval-Christmas/

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/medieval-christmas

Fine article, though I would have referenced the 14th c. romance “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”, which describes in detail even two Christmas feasts.