There is no single person who is associated with Celtic Christianity more than Patrick. He was not actually Irish, but rather British, though he left the comfort of his home and family so that he could live as a foreigner in a land which was cruel to him. At the age of sixteen he was captured, along with many others, and taken to Ireland as a slave. He lived there until he was twenty-three, tending sheep and pigs in the pasture as a shepherd. God gave him a vision telling him to run away and that a boat would be waiting for him to carry him to freedom. Patrick is one of the few early saints who wrote about his own life. In his confession he said that this vision from God came to him because he had fasted and prayed so fervently in the mountains and forests, even in rain, hail, and snow, that God chose him for a special task. After obtaining his freedom and studying the Christian way he eventually returned to Ireland to preach the gospel to those who had captured and mistreated him.

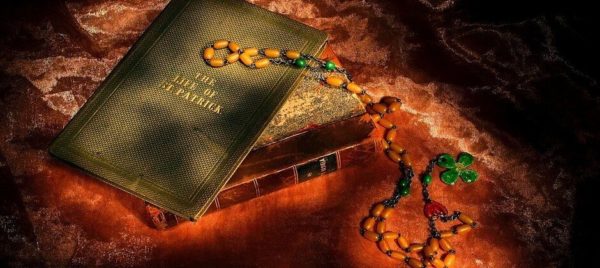

There are a number of sources from which we draw information about Patrick, in this article we will be looking primarily at the life of Patrick written by Muirchú in the 7th century. While the Confessio written by Patrick’s own pen is a more historically accurate source, the Muirchú text shows many important themes in the Celtic imagination. It explores the relationship between Christianity and indigenous Celtic religion, and through poetic imagery it makes an important commentary on how we should integrate new ideas with ancient wisdom. Oliver Davies talks about the dynamic of Christianity and paganism in Muirchú’s telling of the story when he says, “Muirchú has a developed sense of the relationship between Christian revelation and the pagan religion of his ancestors. That religion was not simply a darkness but a preparation for the gospel, and hence his people were always in some relationship with the true God and under the protection of his Providence.”

The early Celtic Christians sought to find their own local versions of stories that came to them from abroad. Patrick embodied the sacred stories of the Hebrew people but with a distinctively Celtic twist. The use of their own heroes symbolically representing the Hebrew prophets shows the way in which their own pre-Christian culture was seen in the same light as the Old Testament. Not something to be thrown away but rather something to build upon. Just as the Hebrew scriptures are echoed in the New Testament, so too the pre-Christian Celtic culture and teachings survived in many ways and created a unique expression of the Christian faith. It is important to remember that all forms of Christianity include aspects of the culture in which they arose. Celtic Christianity is no different in that regard than Coptic or American Christianity.

When Christianity came to the Celts it was already a mixed bag. It was part Jewish, part Greek, part Roman, part Egyptian….you get the picture. To add one more influence was to follow in the Christian path of adapting to local needs. Celtic Christianity retained its own indigenous culture and in that brought a rich vitality to the Western Church. This preservation of the old ways can best be seen in story and ritual, which are less likely to shift with popular opinion than beliefs and doctrines. While the theologians were undoubtedly Chrsitian, the poets and storytellers walked a fine line between the old and the new, sometimes touching their feet down on both sides. We see in the art of the bards and scribes a stronger affinity for the old ways than we do in the words of theologians like Pelagius or Columbanus.

This is also the case with Christianity in general. The old ways of the Hebrews were still very important in the narrative parts of the New Testament even though the New Testament theology can be overly critical of its Jewish roots. Prophecies were fulfilled, psalms were quoted, and the prophets were present. Jesus needed to sit down at the transfiguration with Elijah and Moses because they were still important, even as something completely new was emerging. In the same way we see the importance of the divine feminine, which was so essential to the pre-Christian Celts, emerging in Brigid.

Patrick was clearly associated with the Old Testament characters. It is explicitly stated in a number of places. In particular, Patrick was seen in the role of Moses, Daniel, and Elijah. Just as John the Baptist had been the new Elijah to usher in the new way, so was Patrick seen to walk in the footsteps of the Hebrew prophets. Patrick was seen as driving out all the snakes from Ireland just like John the Baptist spoke out against the brood of vipers of his time and place. Like John, Patrick was associated with Elijah. He had a competition with a pagan druid to see who could start a sacred fire just like Elijah had and he was constantly confronting his people for worshiping false gods.

To mirror Moses, Patrick was a slave in a foreign land who escaped, he had a magic battle showdown with the druids that feels very much like Moses’ competition with Pharoah’s miracle workers, and he established a new law and new way for his people. Like both Moses and Elijah, Patrick’s confrontation with the paganism of his time meant the killing of many of God’s enemies. Patrick performs an uncomfortable number of deadly curses and shows little mercy to those who oppose his idea of God and God’s new people. There is one story in particular of Patrick which demonstrates his likeness to the Hebrew heroes of the Old Testament. It uses the imagery of the opponents of Israel to describe the pagan Irish: the Egyptians who enslaved the Israelite people in the time of Moses, the Babylonians who enslaved the Israelites in the time of Daniel, and the corruption of the worshippers of Ba’al in the time of Elijah.

It just so happened that the celebration of Easter was scheduled to happen at the same time as a pagan festival. Easter is named in the Latin pascha, which is used to describe both the Hebrew Passover and the Christian Easter. Muirchú plainly identifies Ireland with Egypt when he says, “It was coming close to the time of Easter. This was the first Easter to be celebrated to the glory of God in this Egypt which is our island, resembling as it were the Passover, of which we read in Genesis, in the Land of Goshen.”

Patrick decided to have the first Easter celebration in Ireland in the great plain of Brega, near the high hill of Tara, a place of great importance. At the same time, the pagan king Loíguire was preparing his own holy celebration. This pagan festival is described by Muirchú like this, “King Loíguire had also called to Tara all the wise men, those who can predict the future, and those who were trained or could teach every skill and art. Loíguire at Tara was like Nebuchadnezzar at Babylon who had done likewise.”

There was a law at the time, established by the high king of Ireland, that no one could light a fire on that sacred night before the fire in the king’s palace on Tara was lit in the ceremonial way. This was very important and the punishment for breaking this law was death. With great boldness, and as an intentional insult to the king and his pagan ways, Patrick lit his Easter fire in sight of Tara before the king had lit his. The king was furious and sent his chariots to kill Patrick in fear that his new religion would extinguish all the flames of his own religion. The king’s men feared to enter into the sacred circle of Patrick’s fire so they sat outside of it and called Patrick to join them there. The king’s men began to insult Patrick and his god and in response Patrick performed a miracle which lifted one of his opponents into the air and smashed him against a rock, splitting open his head and killing him.

The rest of the king’s men charged at Patrick to kill him but Patrick cursed them in the name of the Lord. A darkness overcame them and they attacked each other in confusion. An earthquake destroyed their chariots and they all tried to flee, many of them dying in the process. Seven times seven men were killed by Patrick. Patrick then escaped by turning himself and his companions into deer and disappearing into the night. They did not run away, however, but rather showed up at the king’s palace to make their challenge once again. As he entered the hall where everyone was gathered, Dubthach, the father of Brigid, stood up and accepted the Christian faith. But, the other poets and wise men decided to challenge Patrick by means of magic.

Patrick and the druids then proceeded to have a competition of spiritual power, very reminiscent of Moses and his staff competing with Pharaoh’s magicians. The druid cast a spell which filled the entire field with snow. Patrick was not impressed and asked if he also had the power to remove the snow. The druid did not. Patrick said he would not go against the will of God to make winter come in the summer so instead he used his power to remove the snow the druid had brought down. At this point it was daylight again and the druid brought a darkness which covered the entire land. Again, Patrick refused to bring darkness upon the people so instead he dispelled the druid’s darkness. Patrick said to the druid, “You are capable of doing ill but not of doing good. This is not the case with me.”

These signs were impressive but still not enough to convince the king. It was decided that they would have a final test, a trial by fire. A structure was built with one half being made of green wood (which shouldn’t burn well) and the other half being made of dry wood (which should go up like a matchstick). The druid put on Patrick’s vestment and stood in the part made of green wood. One of Patrick’s disciples put on the druid’s magical robe and got into the part made of dry wood. The entire thing was set on fire to see which gods would save their people. After the entire thing was set ablaze, the druid’s side burned more fiercely and the druid himself was consumed by the flames, but Patrick’s vestment, which he had been wearing, was left untouched. The opposite happened on the other side. Patrick’s disciple was unharmed but the druid’s robe which he was wearing was reduced to ashes. The king was not pleased about this and tried again to kill Patrick. But it was no use, as Patrick invoked the wrath of God upon them again and many of them were killed. Eventually the king converted out of fear for his own life.

This part of the story reminds one of both Daniel and Elijah. The trial by fire to see which god would burn up the pyre is like the story of Elijah, especially when you think about how Patrick had so many of the pagans put to death, just like Elijah did after he won his own competition of fire. It reminds us of Daniel because the people Nebuchadnezzar had thrown into the fiery furnace were not touched by the flames and were protected by God.

There is quite a juxtaposition to be seen here. Patrick clearly hates the pagan religion and associates it with powerful and wicked kings who take slaves and oppress the people. To be fair to Patrick, he had himself been a slave captured by pagan slave traders. Yet in this story, many pagans prove themselves to be righteous as they work to protect Patrick and his followers. It is the evil of slavery and oppression which Patrick truly fights against. Muirchú clearly sees Patrick as an embodiment of the Old Testament prophets who had to endure the hardship of such pagan kings in their own land. Yet, Patrick chose to light his fire on the same day as the pagans were lighting theirs.

He also demonstrated that this new religion had the same spiritual power as the religion of the druids when he performed miracles in competition with them. He is presented by Muirchú as one who can work miracles just like the druids. In fact, much like in the story of Moses, the miracles he performs are not much different than that which the magicians of the king perform. The real difference between the two, in Patrick’s own words and just like in the Exodus story, is that his magic is worked for good rather than evil.

For Patrick, the ways of the pagan Irish needed to be brought into the Christian fold rather than thrown away altogether. He saw his own work as one which did away with oppression and idolatry and which liberated the Irish from their backwards ways. The New Testament also carries this dichotomy as it is at times completely opposed to Judaism and yet is completely rooted in it and indebted to it. I think there is wisdom in criticizing what was not healthy in the past while still appreciating what was good about it too.

~

For more from this author visit: www.newedenministry.com

Very interesting article. I had not realized St Patrick had so much in common with Old Testament prophets.