Ahlquist: Please tell us about your background.

Asch: I was born in London, England, on October 16, 1968, of first-generation Canadians, both of them opera singers. My ethnic background is Jewish and English (my maternal grandfather was an Anglican from Ipswich, in East Anglia), and the cultural background of my Jewish ancestry is English, Spanish, Rumanian, Dutch, Austro-Hungarian and Ukrainian. I was sent to a French primary school, and then to St. Paul’s School in London – Chesterton’s alma mater, as it happens.

My parents were both practising Reform Jews, and I was brought up a practising Reform Jew: Service every Friday night or Saturday morning (at least from the age of about twelve – before that our attendance had been more irregular); Bar Mitzvah at thirteen; celebration of the major festivals, etc. I have never been an atheist, an agnostic, or even a deist.

On the other hand, we were very much a culturally assimilated family – more so, I should say, than most practising Jews. Also, as I said, my parents were classical musicians, and our house was full of music: my parents’ work, but also lessons (my mother taught and had a studio at home), concerts and records. My parents had a cultivated circle of friends, and my younger brother and I were made very welcome in the discussions that went on in the household. We were good readers early (my parents frowned on TV culture, and though television wasn’t banned, our access to it was restricted), and often taken to concerts, plays, exhibitions, museums, etc. Now most of what we assimilated in this environment was of Christian – and usually Catholic – provenance.

We moved to Toronto in 1984 and I went to the University of Toronto, graduating with a B.A. in English and French Literature in 1990. Early in 1991, I moved to Czechoslovakia, as it then was, and taught English language, literature, and history in Prague until 1998. During this time, I’d holiday in London. When I made up my mind to become a Catholic, in 1994, I went to Farm Street Church for instruction every six months or so till my reception in 1996.

I moved back to London in 1998 and began to work as an editor with the Saint Austin Press in 1999. Since then, I have been involved in Catholic publishing and education.

Ahlquist: How were you first exposed to Chesterton?

Asch: I was aware of who he was at St. Paul’s (there was a bust of him at the school), but I didn’t read any Chesterton until I was sixteen. I had just finished Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray, which I relished, and went in search of something similar – something fin de siècle and rich in verbal swordplay. I found The Man who was Thursday, which seemed to me just the ticket, as it proved to be. I was struck with the distinctiveness of Chesterton’s wit, and that it seemed, uniquely in recent English literature, to dazzle as brightly as Wilde’s. But, as I say, it was distinctive: the style was not the same, nor was the substance. I didn’t read any more Chesterton until, I think, my last year at university; but Thursday had planted a seed, and when I found P.J. Kavanagh’s A G.K. Chesterton Anthology at a bargain price, I bought it. That book exposed me to a fairly broad range of Chesterton’s work.

Ahlquist: What was your reaction?

Asch: It is difficult to feel secure in reconstructing impressions of this kind, in detail, at nearly twenty years’ remove; I was reading an awful lot of stuff at the time, probably a more concentrated variety of material than I have read since. Also, my experience of life, and my perspectives, were in many respects different from what they are today. Perhaps it is enough to say both that Chesterton very quickly became a great favourite with me, and ultimately exercised a profound influence on my life. Humanly speaking, I probably owe more to Chesterton in the matter of my conversion than to anybody else. He wasn’t working on a tabula rasa, though.

God, as the Portuguese proverb has it, writes straight with crooked lines. Looking back now on the slow and often submerged process of my conversion, I can discern many influences – Plato, Sophocles, Bede, Pascal, Dr. Johnson, Newman, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, T.S. Eliot, Hawthorne, George Herbert, and Dickens. There were artists, like Raphael, Giotto, Botticelli, and Mantegna. There were the great architects of the Gothic and the Baroque. Above all, perhaps, there were the musicians: Mozart, Haydn, Purcell, Handel, Tallis, Schubert, and Berlioz (yes, Berlioz!). I couldn’t possibly minimise the importance of Mozart and Haydn as influences, for example, particularly in their liturgical and quasi-liturgical music (I know some will raise an eyebrow at this, but I have no patience whatever with people who dismiss Mozart and Haydn Masses as “operatic”) – the Requiem, the Credo Mass, the Heiligmesse, the Seven Last Words of Christ, and the Creation. Also The Magic Flute which, despite its Masonic associations, had an influence of a wholly Catholic tendency on my sensibility.

But although music can condition one’s sensibility, it can only address ideas obliquely. In Chesterton, however, I was confronted with the specific implications of what was attracting, influencing, and nourishing me. I devoured anything of Chesterton’s I could lay my hands on (no easy task in Prague in the days before the internet): The Man Who Was Thursday was already one of my golden books; then came St. Thomas Aquinas; some of the journalism and writings on Dickens; the comic poems; The Napoleon of Notting Hill – particularly the last chapter, which made a profound impression on me; above all, Orthodoxy. I can still see exactly where I was (a café in Salzburg) when I read it right through for the first time. Reading Chesterton accelerated my progress towards the Church more rapidly and consistently than any other repeated experience I can recall.

All of this was certainly not to me merely a matter of belonging to a group (I have a constitutional distaste for groups) nor even of identifying with a cause or causes (I still fondly remember the rather racy pleasure of being a Jewish admirer and defender of things Catholic). It was a much deeper and dearer thing: the character and the quality of perceptions of life – of my life, and of Life in general – perceptions with which I was profoundly in sympathy. It was my patrimony. It was home, in a sense, and yet I was an alien – I was looking in from outside. Coming into the Church was, for me, very like Chesterton’s description in Orthodoxy of the discovery that this ostensibly strange country is actually your native land.

There were, of course, creedal issues, which I should be obliged to accept, and which I came in God’s good time to accept fully. Had I not done so, I suppose I should have had to face the melancholy prospect of feeling dislocated from all that was dearest to me. But you can’t lie to yourself about things like that – I can’t, at any rate. How I came to accept the dogmas of the faith is a long story, and probably best told elsewhere.

Ahlquist: Did Chesterton strike you as anti-Semitic?

Asch: That is, in a way, a difficult question to answer with a straightforward “yes” or “no.” Let me say straight off that I do not think Chesterton was an anti-Semite. But, in my personal experience, the cards were, so to speak, stacked somewhat unfairly against him (at least initially). You will remember that, after The Man Who Was Thursday, the first considerable exposure I had to Chesterton’s work was Kavanagh’s Chesterton Anthology. In the introduction to that book, Kavanagh asserts that, uniquely in the case of anti-Semitism, Chesterton breathed the air of his time too freely. So in a sense, I never had the opportunity of approaching GKC entirely without preconceptions – at least, never after Thursday. Jews are (unsurprisingly) very sensitive to anti-Semitism and perceived anti-Semitism, and I assumed that there was at least a fairly generally held perception that Chesterton was anti-Semitic.

Perhaps this was a blessing in disguise, as it made me more conscious of anything in Chesterton redolent of anti-Semitism. Had he been a Germanophile too, that might have been a bit much for me at the time; happily, he and Belloc were Francophiles, which suited me down to the ground. I know these are suasions rather than arguments, but you must remember I was a lad of sixteen-seventeen when I began to read GKC in earnest, and suasions counted for a good deal. In any case, I never felt uncomfortable as a Jew in Chesterton’s company. I never felt, “Well, I’ll put up with this nasty business, because there is some real sense in him, and, after all, he writes so well.” That would have taxed my powers a good deal at that age. And one must remember that much of this material was polemical, the sort of writing where one would expect to find a bias if the author was a bigot. Sometimes – though this was rare – I’d come across a remark which gave me pain: I remember, for example, his referring, in Orthodoxy, to Oscar Levy as a “non-European alien” (chapter VII) – though the reference is ultimately complimentary (he calls him “the only intelligent Nietzscheite”). There is an aspect of Chesterton’s thought I am not entirely in agreement with here (and which I’ll come to later). But, even when I first read it, I couldn’t call it anti-Semitic as it contained an element of truth I was already only too familiar with – although I should put it differently.

In all the hundreds of pages of Chesterton I’ve read, I can think of perhaps six or seven instances such as this which a Jew today would be likely to construe – incorrectly, as I believe – as anti-Semitic. It was also not lost on me that there were many more provocative references to Muslims and to Germans in his work than there were to Jews. My abiding impression was that Chesterton was a very good friend – something I should never have felt had I considered him to be anti-Semitic.

Ahlquist: What do you say to people who say that Chesterton was anti-Semitic?

Asch: It depends on whom I’m talking to, and whether they care to listen. Chesterton is very much a late-Victorian/Edwardian writer, in style, sensibility and, obviously, in his frame of reference. It is one of the things that first drew me to him, just as it is perhaps the major reason that some readers are insensible to his stature. I am altogether at home in the world of 19th-century letters: it is my chosen field; and it is a canard (and an increasingly common one) to think that any figure – no matter how far-sighted or prophetic – can be taken wholly out of context. Let us take a couple of cases of changing cultural contexts: Gustav Mahler was a German-speaking Jewish convert to Catholicism, born in what is now the Czech Republic. He was, of course, an Austro-Hungarian composer, but Austria-Hungary no longer exists. What would we call him today? A German? A Czech? A Jew? An Austrian – with all that that now fails to imply? Or suppose Quebec should separate from Canada: would that make an English Canadian born in 19th-century Montreal a Quebecois? A French Canadian? The same is true of intellectual contexts. As circumstances change, the conditions of discourse are altered. We must be sensitive to these changes or we shall simply end by talking about nothing but projections of ourselves. Now, this is nowhere more evident than in matters of language. The meanings and inflections of words change. William Magee, for example, the Anglican Bishop of Peterborough, referred to W.G. Ward as a pervert, by which he meant that he had left the Church of England for that of Rome. So the term was understood. But I can easily imagine some modern clown declaring “We can trace the Church’s paedophile problems right back to the Victorian age. Why, even reputable contemporaries described Ward as a notorious pervert!” In this sense, should GKC have written today some handful amongst the millions of things he wrote ninety years ago, he would probably be called anti-Semitic. But we must ask ourselves two simple questions: would he have phrased them thus today, knowing how they would be construed? And are they, in fact, what we understand by anti-Semitism? The two points are connected, obviously. Did Chesterton hate the Jews – racially, socially or ethnically – and are his comparatively few “anti-Semitic” remarks an expression of such hatred? That, to me, is the real question; and my answer is an emphatic and confident “No.”

Nevertheless, I don’t think it is helpful to dismiss the accusations out of hand as merely cynical, stupid or dishonest. On the contrary, it is worth looking into why Chesterton made the few remarks on which the charge of anti-Semitism has been based. To the best of my knowledge, there is, as I indicated above, only one area where his attitudes are substantially at variance with mine, and that is the extent of the relationship between cultural identity and political autonomy: GKC tended to identify nations with political states – at least ideally; as is evident in his support, in World War I, for the cause of Polish independence (in which I agree with him, incidentally) and Bohemian (i.e. Czech) independence (in which I don’t). Now, between, say, the 1830s and 1945, Nationalism tended to be anti-Semitic, culturally, racially, or both. Also, the identification of nation and race was nearly universal. While the hatred of other peoples is as old as the hills, we tend to forget that genetic racism is a relatively recent phenomenon.

If we turn to the Jews in this period, we find them to be everywhere a cultural and racial minority in environments of growing nationalist activism: an activism which tended to understand itself in racist terms. This was not necessarily or invariably an anti-Semitic phenomenon, nor were Jews themselves free from the tendency. The most famous theorist of race was Joseph Arthur, Comte de Gobineau (1816-1882), whose magnum opus on the subject was The Inequality of Human Races. Because of his racism and influence on Wagner, Gobineau is usually thought of as an anti-Semite, but he wasn’t: he believed the Jews to be one of the superior races. The same was true of Benjamin Disraeli, a great hero to most Jews, who declared in Coningsby that “Race is everything; there is no other truth.” Indeed, Coningsby – an enormously stimulating political novel – is somewhat marred for me by the author’s occasional (pro-Semitic) emphasis on the importance of race. Ironically, our old friend Oscar Levy was both an admirer of Disraeli (he translated him into German) and much influenced by Gobineau’s racist theories: he wrote the introduction to the English edition of The Inequality of Human Races.

The reaction of assimilated Jews to the hostility of their environment tended to be of two kinds: a determination to succeed in defiance of every barrier erected against them, or a wholesale rejection of the establishment. In other words, one tends to find a high proportion, among assimilated Jews, both of conservative supporters of “The Establishment” and revolutionaries. This is tragic, particularly as this attitude was the fruit of centuries of proscription and abuse. In any case, it is, with the new racism, one of the two main reasons for the anti-Semitism of 19th-century Nationalism: more often than not, assimilated Jews supported the Austrian, Russian or German imperial governments against which the Nationalist Poles, Czechs, Hungarians, etc. were struggling. After all, to the extent that the Jews had succeeded in attaining any measure of security and success, it had been in the established order the Nationalists were seeking to overthrow, Nor could the Jews expect better treatment at the hands of (often) racist ideologues: insofar as the Austrians, Germans, and Russians governed multinational empires, they had (particularly in Austria) to tolerate – at least to a limited degree – ethnic groups other than their own; the Nationalists did not. And in Chesterton’s beloved France, with its aggressive political factions and endless social upheavals, anti-Semitic sentiment was rife: representatives of all parties, whether Republicans like Barrès, Royalists like Maurras and Léon Daudet, or Leftists like Clemenceau, were often coarse or violent in their anti-Semitic language. (In fairness, I should add that Daudet and Barrès both renounced anti-Semitism well before the advent of Nazism, while Maurras and Clemenceau were Germanophobes).

To those who are intimately familiar with this era, the so-called “Jewish Problem” was not mere anti-Semitic rhetoric (though the tag might make us wince today with the advantage of hindsight). Indeed, there were many prominent Jews who felt the same way – it was, in fact, one of the presuppositions of the Zionist movement.

Now, as regards GKC, I should say that three things here are of particular relevance. On the debit side, I believe that he exaggerated the continuity of Nation-State, and that consequently he doubted the extent to which Jews could become fully and happily integrated into a predominantly Gentile Patria. He could see, as a matter of daily fact, the strife that existed between the Jewish communities and the Gentile majorities; and that where national sentiment was strongest, this friction was most intense. He also disapproved of the cosmopolitanism of many secular Jews, which he tended to see (and here I agree with him) as antipathetic to patriotism.

To his credit, however, one must add two very important points:

In the first place, Chesterton’s Nation Statism didn’t translate into anything like the fundamentally anti-Semitic position of most Nationalists. On the contrary, in accordance with his principles, it led him to espouse the cause of a sovereign state for the Jews in the Holy Land. Chesterton was, in fact, a Zionist, and said as much, frequently. I’m not sure that any Jew of my acquaintance is aware of this fact; but fact it is.

Secondly – and perhaps more remarkably – Chesterton was one of the few men of his time who utterly rejected the tenets of race identity. It is impossible to read Chesterton in any depth without being confronted over and again with his contempt for the racist interpretation of culture. He is forever ridiculing “Celtic” culture, “Teutonic” culture, “Anglo-Saxon” culture, “Aryan” culture. It led him to be – with Churchill – one of the few Englishmen to be utterly, unremittingly, hostile to Hitler and Nazism from the first. And in his anti-Nazi diatribes, we find GKC coming explicitly to the defence of the Jews. Again, this is a fact sadly unknown to most Jews.

These facts become the more significant when we return to the question of historical context. Is it irrelevant to the question of Chesterton’s supposed anti-Semitism that he excoriated Hitler as a racist in his weekly journalism when figures – still respectable in Jewish circles – such as Shaw and Lloyd George were praising Hitler as the greatest thing to come out of Germany since the Reformation?

Again, I wonder how many Jews are aware, today, of the pervasiveness of racial assumptions before World War II. Unless their attention is drawn to it, most people tend to assume that any writer not identified with anti-Semitism was probably fairly “sound” by modern pc standards – especially if they were “progressives.” For instance, it is widely, and incorrectly, assumed (by Jews among others) that H.G. Wells (an author whose fictions I greatly admire) wasn’t anti-Semitic because he was a “progressive.”

Finally, people simply weren’t as sensitive to these issues – as hypersensitive, one might sometimes feel – as they have been since the War. One finds anti-Semitic gibes in the correspondence of Byron, for example, and Byron was unusually sympathetic to Jews by the standards of his society. And it was Browning, a poet Jews regard (rightly) as pro-Semitic, who quipped:

We don’t want to fight,

By Jingo, if we do,

The head I’d like to punch

Is Beaconsfield the Jew.

One even finds Lord Rosebery – a man without a shred of vulgar anti-Semitism, and whose blissful marriage to Hannah de Rothschild led to grumbles of Jewish political interference – accused of anti-Semitism because of a few casual witticisms.

Chesterton was probably the most prolific major author of the last century, and he was a religious, political, and cultural polemicist, a journalist with a daily column for decades. It’s simply not plausible that an author answering to that description could be anti-Semitic without leaving a large trail behind him, particularly in the late 19th– to early 20th-century. It must, I think, be conceded that Chesterton does not display any interest in the deep and ongoing relationship of the Jews to the Church and Cosmic History that we find in the writings of writers like Bloy, Péguy, Pascal, Solovyov or Mickiewicz – but then, attitudes such as these have always been rare, and the same could be said of scores of authors never accused of anti-Semitism. But had Chesterton lived through the Second World War, I should not, for my part, be surprised if he had turned his attention to this phenomenon. And when GKC wrote, in response to the early Nazi persecutions, that he and Belloc were prepared to die defending the last Jew in Europe, I am quite prepared to believe him. There is nothing of bitterness in his tone, let alone hatred. I have always found him the very best company, the most lovable, as well as the most engaging, of writers.

Ahlquist: You have no doubt heard the charge that the Catholic Church is anti-Semitic. As a Jewish convert to Catholicism, you must have some interesting things to say to people on both sides of the aisle.

Asch: Well, actually, the only anti-Semitic experiences I had before my conversion were at the hands of Protestants and agnostics. No doubt that was mere coincidence, but in any case, I never associated anti-Semitism with the Catholic Church particularly, nor was I brought up to it. I certainly never remember my parents saying anything of the kind. As a child I had learned something of the pogroms in Eastern Europe, but though the Poles were Catholic, the Russians weren’t. Again, the Holocaust tended to be seen as a German crime, rather than a Christian one; certainly not a specifically Catholic one. At university, when I began to be more aware of Catholicism, I read Pascal – who is an admirer of Judaism – before I read Kavanagh, and then, in Central Europe, I found that it was the practising Catholics I met who were most friendly to Judaism – much more so than the Secularists. Again, I was aware, at least from my university days, of John Paul II’s very warm relationship with Judaism, which made an impression. And I have never forgotten a remark made by one of my parents’ friends in a particularly interesting conversation from this time, that Luther was the first anti-Semite. I don’t believe it influenced me, but it certainly didn’t incline me towards a belief that the Catholic Church had a monopoly on anti-Semitism. And since becoming a Catholic (except where long-standing ethnic frictions are concerned – among the Poles or Irish-Americans, for example), I have not found anti-Semitism in Catholic circles at all.

I did harbour the suspicion, as a Jew – which I am persuaded I shared with most Jews (certainly most of my acquaintance) – that Christians generally were anti-Semitic, and, vaguely, a sense that perhaps all non-Jews were – at least in Europe, the Americas and the Middle East. And I’m afraid I don’t believe that most Jews who feel this way try very hard to rationalize (responsibly, at least) what would appear to be such an extraordinary conviction.

As I have said elsewhere, Jews tend to be extremely sensitive to any perceived hostility or criticism, and this is, after all, only to be expected. What Christians must try to realise – if they are going to reach Jews – is the extent to which centuries of persecution, extending well into this century, have branded these insecurities into the Jewish psyche. I suppose this is a truism, but it is one which cannot be repeated often enough. It has led to a warping of Jewish objectivity. For example, 19th-century England and Austria-Hungary, where opportunities for Jews and acceptance of Jews were much more widespread than elsewhere, have nevertheless been characterised by Jews as fundamentally anti-Semitic cultures. While there is an element of truth in this (and sometimes more than an element), it also involves a considerable distortion of perspective.

The saddest aspect of this is that it has led to an attitude of cultural solipsism among Jews: nothing is fully real, or at least important, outside the circle of Jewish concerns. In this sense, the creation of Israel is perhaps the best thing that has happened to Judaism in centuries, if only because the Jews have had to shoulder the responsibility of governing other peoples. And this is the key to much historical anti-Semitism. Anyone with a knowledge of history is aware of the cruelty which nations visit on one another, and particularly on weaker cultures, vanquished nations or ethnic minorities. And minority cultures – or former minorities – are jealous of suffering: the attitude tends to be No one has ever suffered as we have suffered. The Poles complain of the Germans and the Russians. the Jews complain of the Poles. The Irish were abused under English rule, yet Irish-Americans have been notorious in their treatment of Jews and Blacks. The French-Canadians also complain of abuse at the hands of the English, yet the Jews and Indians could tell you a thing or two about the French-Canadians. The Czechs were mistreated by the Austrians, the Slovaks and Gipsies by the Czechs. The Slovaks, in their turn, have a very poor track record with Gipsies, Jews and ethnic Hungarians…and on and on it goes. And now it is the Jews themselves, in Israel, who stand accused of the same crime.

Something which was apparent to me some time before my conversion was the inconsistency of the charge of anti-Semitism against specifically Christian culture: Islam is quite as anti-Semitic as the West, and both Imperial Rome and Macedonian Greece persecuted the Jews. If anything, it tended to confirm two things in my mind: the peculiar history and identity of the Jews, and the reality of fallen human nature. Perhaps, in a generation or two, conditions will be propitious for a more magnanimous exchange of perspectives.

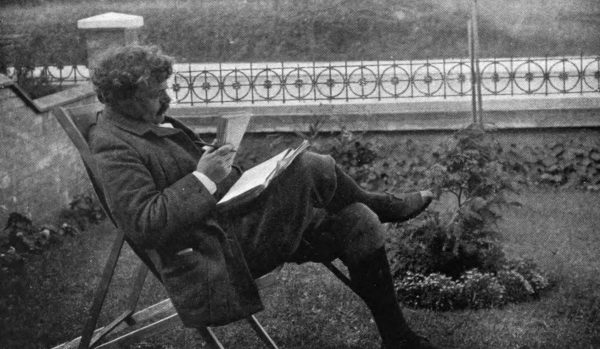

Cover photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.