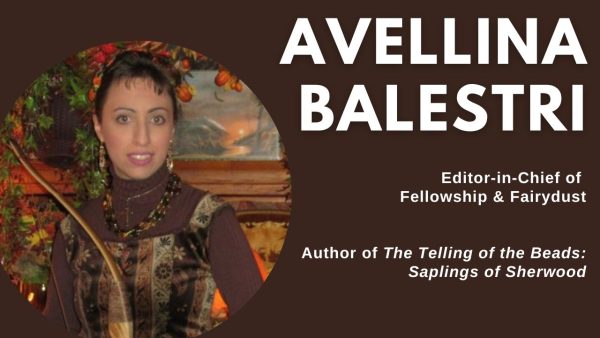

Fellowship & Fairydust, Editor-in-Chief Avellina Balestri has contributed many poems and other creative works to the magazine and other publications over the years. She broke new ground in 2022 by releasing her first novel, a Robin Hood story entitled The Telling of the Beads: Book I – Saplings of Sherwood.

Here is the book’s summary:

Robin Locksley is the heir to the last Saxon noble house in Nottinghamshire. Since the time of William the Conqueror, his family has been beleaguered by those who seek to extinguish their lineage and seize their estate. Roger Cavendish is the son of the ruthless and power-hungry Norman lord whose property borders Locksley lands.

For over a century since the conquest, the Cavendish family has sought to secure predominance in the region through any means necessary. Each raised to uphold opposing ancestral legacies, Robin and Roger find themselves crossing paths through their common bond to the land. They meet eye to eye, sky blue and hawk gold, catching glimpses of each other’s souls as they struggle under their own personal burdens.

But while one is yet a child and the other hardly a man, a twist of fate intensifies the generational feud and kindles the first sparks of a raging fire that will one day consume their world. Destiny will immortalize them in story and song. Unfolding in an era dominated by feudal conflict and imbued with religious faith, this introspective drama puts flesh upon the bones of legend and takes an intimate character-driven approach to retelling one of the most famous heroic journeys in the annals of literature.

The book (available on Amazon) was released to positive responses both from reviewers and readers. Joseph Pierce praised the book in The Imaginative Conservative, calling it “a truly masterful piece of storytelling and as near to the real or legendary Robin Hood as any of us is likely to get.”

Avellina spoke with F&F contributor G. Connor Salter about the book and her writing process.

Connor: To start off Avellina, congratulations on releasing your book. I’d like to start by asking an obvious but necessary question: what inspired you to start this book?

Avellina: Thank you so much, Connor. Well, like many such projects, this one has been a long time coming. As I mentioned in my author’s note, I have had an affinity for the legends of Robin Hood since my childhood. I have been jotting little stories about the Prince of Thieves for almost as long as I can remember.

It took until around 2017 for a distinct idea to form in my head for a proper retelling, based on the idea of taking the “daughter of Robin Hood” trope and turning it on its head by instead featuring a daughter of the Sheriff of Nottingham as a major character. Some years hence, I found myself with a full-length series on my hands, with the first book, Saplings of Sherwood, serving as an introduction to the characters and their world.

Connor: How many books will be in this series?

Avellina: At the moment, I have seven planned, though that number may change if the story dictates it, either gaining or losing a book in the process of expanding and contracting plotlines. I think that the integrity of the project is the most important thing, and the length must be whatever is necessary to give it a satisfactory conclusion with all the loose ends tied up.

Connor: Much of the book features a young Robin and a young Marian getting to know each other. I know you felt the need to give readers a little romance, but not make it “cringeworthy.” What was it like finding that balance?

Avellina: It was quite challenging. I am not typically good at writing romance, and Robin/Marian has been done to death as a couple in countless retellings. That made it doubly difficult to create something which both feels original but also hits the main traditional story-beats. The first draft required major rewrites, mainly in the chapters covering them as teens, and I had to drop several chapters completely.

As it stands now, I’m fairly satisfied to have given readers less of an outright romance and more of a glimpse into the growing tenderness and empathy shared by two young people against the expectations of a divided society.

Connor: The Robin Hood stories have been around for several centuries, and we’ve seen everything from action hero Robins played by Russell Crowe to Robin hunting Morgan Le Fay in T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone. Which Robin Hood versions have you enjoyed or hated?

Avellina: My first Robin Hood was the Disney fox voiced by Brian Bedford. Hard to really top that one for fond memories. I also grew up with the Richard Greene series from the 1950’s. For all its foibles in terms of consistency and chronology, it showed that writing new adventures of Robin Hood was something that could still be done and was genuinely moving as a demonstration of English resilience and identity in the aftermath of WWII.

Two other classics I grew up with, and re-watched over the course of the writing process, were the Errol Flynn version and the Richard Todd version. Both had their own pros and cons (Flynn being rather hyper, and Todd being rather too morose), but both also stick fairly close to the traditional story beats, which I appreciated. I cannot say I am a fan of the hammy Kevin Costner version, nor the gritty Crowe film (which hardly counts as a Robin Hood film really, and the title feels rather forced onto it as a sales pitch). In terms of series, both Robin of Sherwood from the 80’s and the more recent BBC series have their high and low points. The former certainly inspired me to lean into the Green Man mythos, whereas the latter inspired me in how I chose to depict Guy of Gisborne.

Possibly my least favorite rendition is Robin and Marian, featuring Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn. It is one of those films with a stellar cast who had sub-par material to work with, particularly the almost laughably bad finale.

Connor: The Robin Hood stories often mix historical events with legends and occasionally bits of magic that we might today call fantasy. Given that mix, you can describe Robin Hood as historical fiction or fantasy. What genre do you place this novel in?

Avellina: My version definitely leans more towards historical fiction. I aimed for realism when dealing with life in the 12th century and how it was shaped by the long legacy of the Norman Conquest in the 11th century.

As the series progresses, we also lean into the way the Crusades affected individuals and societies. Due to the fact that the legendarium has been embroidered and compiled over the course of many centuries, however, I do allow for some “elbow room” for aspects from different time periods to do justice to the story as it has been passed down to us. In terms of fantasy elements, I do try to incorporate the mythic and supernatural into the mundane day-to-day of Robin’s world. But I do not consider this fantastical as much as I consider it a reflection of the numinous which penetrates our reality here and now.

Connor: During the writing process, you would share excerpts from the book on your Facebook page. How did this influence your writing process?

Avellina: It was greatly helpful for me, not only because of the feedback I received from readers, but also kept me going on the road to completion. It gave me motivation to finish one section at a time and see what others thought of the progress. I know that some authors are wary about sharing their work pre-publication, and sometimes with legitimate reason, but I found the benefits outweighed the risks. I am a very communal kind of writer; I like to pull people into my projects and get them involved. I have written some of my best dialogue thanks to real conversations I have had with my friends during project discussions.

Connor: You talk in the book’s foreword about recapturing an important theme from the early Robin Hood stories: Robin as a religious man. Did you find that challenging, given how many depictions ignore that angle?

Avellina: I actually found writing him that way to be quite natural, because I have always considered him part of the folklore of Christendom. It is simply self-evident that medieval England should be depicted as a richly Christian, and specifically Catholic, universe. As you point out, this is knit into the original ballads of Robin Hood. For example, Robin’s devotion to the Blessed Virgin is so fundamental to his respect for women. He is shown praying the rosary and risking capture to attend mass on Marian feast days. The fact that the richly religious elements of these tales tend to be stripped to appeal to secular audiences undercuts their very poignancy, including their parable-like format, where the first are made last, and the last first. I seek to restore that which has been removed in a way that feels organic rather than forced.

Connor: I was particularly struck by the fact that Robin’s manhood journey and his Catholic faith become intertwined, yet you resisted what we might call “the Mel Gibson approach.” There’s Catholic imagery, but you didn’t go for the bloodiest Catholic images you could muster.

Avellina: Ah, dear Mel! He is one of my pet peeves, I’m afraid. I could go on for hours decrying the many sins against historicity and good taste to be found in his productions. This is not to say he is devoid of talent, but he lacks both subtlety and sensibility when it comes to storytelling.

But what is even more egregious, in my humble opinion, is his use of Christian imagery alongside plots that fail to capture the heart of the Christian faith, which is all about loving our enemies. We can see this clearly in both Braveheart and its close cousin The Patriot. The trappings of Christianity are there, sometimes in a very in-your-face manner, but they do not represent anything deeper for the characters than a shallow justification for their own vendettas. This is something I always strive to avoid in my writing.

If Christian, and more specifically Catholic, symbols are going to be used, they must mean something which is genuinely challenging to the characters and the audience alike, not merely exist to reinforce our characters own adrenaline-driven violence. Also, even when violence is a component of story I am telling, I do my utmost to avoid tasteless gore fests that serve no greater purpose than shock, something which Mel falls into again and again in his films.

Connor: In the story, Robin gets angry at his father’s compromises with oppressors, but his father is portrayed as a good man rather than a spineless one. You consistently aimed for nuance over angst. Was that a conscious choice?

Avellina: Yes, I wanted to show that there is not always a single right way of dealing with complex situations. Robin is a mix of his mother, who wants to rebel against the Normans, and his father, who realizes what a failed rebellion would cost their people.

Robin’s instinct is to be like his mother, and take on the oppressors, but this comes at a cost for the very ones he is trying to help, and his father’s caution tempers him. This is in stark contrast to the way Mel Gibson portrays his heroes such as William Wallace being justified in everything they do, with minimal negative consequences due to their rashness, because, well, “freeeeedommm.” Everyone who comes at the situation differently is portrayed as immoral, self-serving, and responsible for anything that goes wrong. I find this disheartening, especially when the more violent route is constantly glorified and seeking diplomatic solutions is degraded. This is not that to say that, sometimes, there is no choice but to fight, and Robin himself is going to find himself in that position ultimately. But his father’s prudence never completely leaves him, and it is that restraint that keeps him sane as an outlaw prince.

Connor: You balance light and dark moments throughout this book in a way that I realized I hadn’t seen many authors do. It’s become very popular to write grim deconstruction stories that make the medieval period seem completely filthy and brutal (sometimes called “grimdark stories”). You opted to have some dark moments—Norman nobles abusing female serfs, a few deaths—but they feel tragic instead of grimy and sleazy. How did you go about creating that balance?

Avellina: I do try hard to keep a balance of light and dark scenes without creating tonal whiplash in the wider story. Since it is based upon history, I believed that the world itself needed to be fleshed out enough to feel real, and once that was accomplished to my satisfaction, I worked to create a sense of genuine realism in the themes that were explored and the actions depicted.

Too often, the term “realism” has been used as shorthand for grimdark ala George R.R. Martin, but that is not truly realistic, since good experiences are just as real as bad ones. I think the key here is to resist, in all instances, dehumanization. Creating a universe where only bad things happen, and everyone is morally ambiguous, is a form of misery porn. I do not want my sales coming in from that lowest common denominator. I want even the elements of darkness in my stories to cause readers to reflect all the more on goodness, truth, and beauty, and we need to have that be present in order to recognize the contrast. In this, my method as a Catholic storyteller is more akin to J.R.R. Tolkien than Flannery O’Connor. I show the lack of grace, but also the presence of grace in as vivid a manner as I can. The sun shines out all the more brightly through the clouds.

Connor: Christians discussing religious elements in fiction will often bring up J.R.R. Tolkien as an example who made his faith implicit in his fiction, and C.S. Lewis as someone who made his faith explicit in his fiction. As a writer, do you lean toward one side of that spectrum, or do you feel that’s a false dichotomy?

Avellina: Well, in terms of historical fiction, I feel that my method is closest to Leo Tolstoy in his epic War & Peace. I appreciate richly layered narratives imbued with a profound sense of spirituality and exploration of morality, using the background of the Napoleonic Wars in Russia.

In fantasy worlds, direct references to this-world religions tend to detract from the whole (thus the need to either use allegory or allusion), but in historical fiction, one can really lean into the way that Christianity (or indeed any other faith, depending on the setting) permeates a particular culture and time period, which then inevitably shapes the characters and their philosophies of life. This is how I have utilized world-building in my retelling of Robin Hood.

Connor: Any idea when the next book will be out?

Avellina: It will be a bit touch and go, as I am also in the process of writing a trilogy set during the American Revolution. But the sequel to Saplings of Sherwood, entitled Small Apples Grow, is halfway written in rough draft form. Hopefully it should be published some time in 2024.

Connor: Thanks for your time, Avellina. On behalf of all the F&F volunteers and readers, congratulations on your publication.

Avellina: Thanks so much!

Avellina Balestri is a Catholic author and editor based in the historic Maryland-Pennsylvania borderlands. Her stories, poems, and essays have been featured in over thirty print and online publications. Read more of her work here. Telling of the Beads: Saplings of Sherwood is available for purchase on Amazon.

In 2019, Balestri hosted a Fellowship & Fairydust literary conference at Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford, England, commemorating the legacy of J.R.R. Tolkien. Tickets are on sale now for the 2023 conference, Passages of Light.

People who want to help out with the conference’s costs can do so at its GoFundMe page.

1 thought on “Writing a Robin Hood Novel: An Interview with Avellina Balestri”