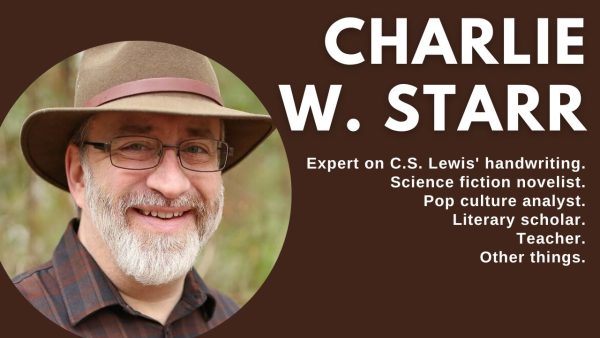

Dr. Charlie W. Starr (D.A., Middle Tennessee University) has an unusual specialty in C.S. Lewis studies. He’s an expert on C.S. Lewis’ handwriting—what it looks like and how it changed over time. This makes Starr a unique resource on manuscript research—he can help scholars determine when a piece was likely written.

The specialty also proves especially useful when studying someone like Lewis. As Starr noted in a piece for VII, Lewis had defective thumbs. Sports proved impossible, and Lewis found writing with a pen was one of the few non-awkward tasks he could do with his hands. The thumbs also may explain why Lewis never used a typewriter.

Over the last 30 years, Starr has taught at the high school and college level, including at Kentucky State University, Alderson Broaddus University, and Northwind Theological Seminary. His research on Lewis has appeared in popular sites like cslewis.com, the books J.R.R. Tolkien and the Arts and C.S. Lewis and the Arts, as well as almost every major Inklings studies academic journal—including The Journal of Inklings Studies, Mythlore, Sehnsucht, VII, and The Lamp-Post.

Some of his notable research includes a Sehnsucht piece co-written with Dr. Brenton Dickieson on a never-finished Screwtape Letters sequel. The research later played a role in Dickieson’s much-noted Mythlore essay “A Cosmic Shift in the Screwtape Letters.”

Starr has also published several books. His early books were spiritual nonfiction—Life in the Spirit: Studies in Romans 1-8, and Honest to God: Wrestling Your Way to Intimacy with the Creator.

Thus far, he has published three books of Lewis scholarship: The Lion’s Country: C.S. Lewis’ Theory of the Real, The Faun’s Bookshelf: C.S. Lewis on Why Myth Matters, and Light: C.S. Lewis’ First and Final Short Story.

Last but not least, Starr writes fiction, including King Lesserlight’s Crown: A Children’s Story for Grownups, Too, and an ongoing sci-fi series, the Tales of Solomon Star.

He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

What was your first exposure to C.S. Lewis’ work?

I first encountered C.S. Lewis in my freshman year of college. I took an apologetics class which required I read Mere Christianity. After that I read The Great Divorce that year, and then in the summer I read all of the Narnia books in a week. Of course, I loved all of these books, and I continued to read Lewis off and on for years. In the early 1990s, however, I finally read Till We Have Faces. At that point I became completely hooked, and decided to dedicate my research work entirely to Lewis (and the Inklings).

An author’s handwriting is a unique thing to focus on. What led you to that specialty?

It was a complete accident. In 2011, I was given the opportunity to publish Lewis’s “Light,” manuscript, the final draft of the short story published in 1977 as “The Man Born Blind.” “Light” may be Lewis’s most mysterious manuscript. The story itself is strange and has been subject to multiple interpretations. The manuscript surfaced over a decade after Lewis’s death. Kathryn Lindskoog accused Walter Hooper of forging the story himself, and two people who knew the story to be authentic—Owen Barfield and Douglas Gresham—each claimed different dates for when the story was written. Barfield dated in the late 1920s, before Lewis became a Christian. Gresham dated in the 1950s, well after Lewis’s conversion.

While researching my book on “Light,” I came across a statement by Hooper that helped me assign a date to the manuscript (both versions). Hooper pointed out that Lewis’s handwriting changed throughout his lifetime, sometimes deliberately and markedly so. From this little clue I realized that if I could map out all the changes in Lewis’s handwriting throughout his lifetime, I could date “Light” (and any undated Lewis manuscript).

I did a preliminary survey to conclude that the versions we have of “Light” were both written in 1944 or 1945. Once the book was complete, I realized that I needed to make a complete and thorough map of Lewis’s handwriting, year by year. I finished this project with the help of a great undergraduate assistant and images from the Wade Center who also gave me a grant to go there and date over 200 undated manuscripts in their collection.

All these findings were published in VII (an essay entitled “Villainous Handwriting”), and I have since been privileged to work with Lewis manuscripts on a yearly basis. Some amazing discoveries have resulted.

I understand that along with writing about Lewis’ handwriting, you’ve consulted on several projects dating his manuscripts. Can you tell us about any of those experiences?

In addition to dating a variety of manuscripts at the Wade Center, I’ve been able to work with a variety of wonderful Lewis scholars dating and transcribing their Lewis discoveries.

Crystal Hurd published the hilarious “Padaita Pie” manuscript—a notebook in which Lewis and his brother wrote anecdotes about their father over a decade’s time. The first discovery I was able to make about the text was that it had been mislabeled as having been written primarily by Lewis’s brother, with Lewis only making a few entries. Based on handwriting analysis, I was able to prove that the reverse is true. C.S. Lewis wrote most of the entries. Secondly, I was able to date each entry for Dr. Hurd’s project, again by examining the handwriting. What had been thought was a notebook written in only a few years actually took a decade.

Another interesting project involved dating Lewis’s poetry. When Don W. King’s collection of Lewis’s poetry was released, he dated each poem and published the poems in chronological order. At the back of his collection, King lists nearly 40 poems which he could not confidently date. I contacted Dr. King and told him I could help with dating the undated poems. We worked together to find images of the poems in question (and some others). In the end I was able to confirm dates on many poems which King had dated with a question mark, redate a few of the poems, and, most delightfully, date all but one of the undated poems. I have yet to publish these findings.

I could share more stories, but there is one, another I have yet to publish the results of (I was about to just when COVID hit), which I think is especially significant. I’ll just say this about it: based on changes in Lewis’s handwriting which occurred in the summer of his conversion to theism (1930), I can confidently argue that Lewis’s response to his conversion was a gush of poetic activity.

Lewis had thought of himself as a failed poet. He’d wanted to be a successful poet for years. His response to becoming a believer in God, however, was to write up to 20 poems in a matter of only a few weeks. His love for God, combined with his surrendering poetic ambition, made for what he thought was the best poetry he’d written up to that point in his life.

You’ve had a particularly prolific career—over 100 popular articles, various academic pieces, nine books so far, and over 30 years of teaching. What has helped you stay productive?

I will give a three-part answer:

1. College professors complain about how tough their jobs are. Nonsense. I was a high school teacher before becoming a college professor. I know how easy I had it once I was left high school for college-level teaching. Only having to teach two or three classes a day? Heaven! And so, I used the time I had available to learn and to write.

2. Lewis wrote so much because he enjoyed writing (far more than I do). While you are kind to point out the number of books I’ve written, I’m willing to confess that they don’t add much to my income. When someone says to me, “Hey, I read your book!” I reply, “Oh, so you’re the one.” Well why then write? One reason: because I like to. And I like writing academic essays as much as I like writing my science fiction and fantasy tales. But there’s another reason.

3. Obsession (or perhaps a calling). I write because I have to. The first piece of advice I give to anyone who tells me they’re thinking of writing a book is, “Don’t do it. Unless you can’t help yourself, don’t write. Unless you’re willing to suffer rejection slips, long hours of isolation, and a constant sense of doubt, frustration and the fear that you may go ignored, don’t write. There’ll be a hundred thousand books published in America every year. 99.9% of them won’t sell 500 copies. But if you have to write, despite all the obstacles you may face, then do it.” So, I stay productive because I don’t have a choice. Even now, in this time where I don’t have a college teaching position anymore (due to my institution closing), and may have to pursue a job that doesn’t allow time for writing, even now I’ll still find time to write, probably at night when I should be going to bed early.

You seem to have a broad range of interests, popular as well as literary. When I was researching your work, I discovered you contributed not just to the SmartPop anthology on Narnia, but also its anthologies on King Kong, the X-Men and Halo franchises, and the TV shows Battlestar Galactica and Lost. Do you deliberately try to keep things varied, or does it happen naturally?

It has been primarily by providence. I do have a variety of interests, but the opportunities to write in them have largely come by grace. The SmartPop series is a good example. They initially contacted me to write a chapter for the Narnia book. After that I was able to write for other books in their series. I wrote for a national church magazine on Christianity and culture (then focusing only on film) for a decade. Currently I’m focusing on writing about Lewis and writing a science fiction series. As people contact me to write about other topics, I happily do so.

Looking over your work, it occurred to me that much of your Lewis research deals with epistemology—the study of knowledge. For example, you’ve published two essays (in VII and Mythlore) on Lewis’ epistemology, and The Faun’s Bookshelf and The Lion’s Country both deal with epistemological concerns—what do we know as reality, what we know as myth, what we learn from each. What fascinates you about epistemology?

You have found me out! My book on “Light” also deals with epistemology. I’ve had a longstanding interest in the idea of truth, philosophically and theologically, but Lewis stepped things up a notch for me when I encountered a single sentence in Perelandra:

“Long since on Mars and more strongly since he came to Perelandra, Ransom had been perceiving that the triple distinction of truth from myth and both from fact was purely terrestrial-was part and parcel of that unhappy distinction between soul and body which resulted from the fall.”

My first shock wasn’t in regard to the possibility that myth could be true (that was my second shock). My first shock was how there could be a difference between truth and fact. What was that difference? And then, of course, how could myth possibly be true. This single sentence in Lewis’s second sci-fi book sent me on a journey which ended up in a 350-page doctoral dissertation on Lewis’s epistemology focusing on fact (which meant focusing on its synonym reality), truth (which meant also focusing on reason), and myth (which meant also focusing on imagination and its connection to meaning, reason, and truth). All of this also meant considering Lewis’s ideas on art, language, literature and the human poetic sensibility.

I did not publish the dissertation as a whole. But its findings have certainly provided the core of my understanding of Lewis’s thought.

You’ve described the Solomon Star series as an attempt to “follow in C.S. Lewis’ footsteps in writing science fiction.” What are some ways that Lewis’ writing informed the series?

Because of Lewis’s books, my sci-fi series is less didactic than it might have been. I don’t preach, I show. Many of Lewis’s ideas, then, permeate the books in the sense that they permeate me. It’s a blessing to surrender yourself to a good thinker/writer—to read everything they’ve written and become steeped in their thought. The surrender gets you inside their heads so that you take on their thought system both consciously and unconsciously.

Of course, this can be dangerous. What if I pick the wrong thinker? But I have found that the best learning occurs through surrender which then leads to the ability to critique and doubt. Those who begin with doubt, seldom learn much from any of the great masters of history. Such people are too much like the dwarfs in Lewis’s Last Battle. As a teacher I recommend this to other teachers: don’t teach your students to think for themselves. Teach them to join the community of thinkers who are smarter than they are, the community that’s been carrying on a conversation for the last 2,500 years. In doing so, students’ thinking will improve and the ability to critique will naturally follow.

In short, though, Lewis is often influencing my books even when I don’t know he’s doing it! One thing I’m doing definitely comes from Lewis: Lewis said we don’t need Christian books. We need books about other topics written by Christians with their Christianity latent in them. I set out from the beginning to write books that anyone would like regardless of their faith system (or lack of one). My plan is that the books will then deal with more overtly religious issues as they progress.

Did any other sci-fi writers influence the books?

Frank Herbert’s Dune series, Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, Star Wars, the logical problem-solving in Isaac Asimov’s books, and the style of writing in Ray Bradbury’s works. But there are also some non-sci-fi writers who’ve helped me along the way, especially Homer, Dante, William Faulkner, Herman Melville, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Sometime last year, I recall you talking about plans for a new Solomon Star book. Care to give us any updates on that?

This will be book four in the series. The first book, The Heart of Light, is the most mythic, the most literary of the books so far. Books two and three (The Darkening Time and The Aurora Gambit) which cover what I call the Overlord War, are more adventurous—though they take up issues involving propaganda, heroism, and artificial intelligence among other things.

In book four, The Judas Wish, I bring much that happens in the series to a central conclusion. The book will be a murder mystery, a historical exploration, an archaeological treasure hunt, and a theological exploration involving a search to find the ancient lost world, Earth, and the God who may very well live there. The Judas Wish, which will be the most overtly religious book of the series so far, is proving to be a tough nut to crack.

I’m 82,000 words into the first draft. I’ve figured out what pieces need to be filled in (so that I’ve actually written the beginning and the end and most of the middle). The first draft may make it to 100,000 words! I’d like to have it done by the end of 2023. But then that will still only be the first draft. Revisions will certainly follow. But I already have a publisher interested in releasing the book.

One thing I’m interested in: beta readers—people who’ve come on Solomon’s journey with me through the first three books and would love to read the fourth book in manuscript to help me make it the book I want it to be.

Any nonfiction projects or presentations in the works?

I’ve got several presentations coming up in the fall of 2023: A Zoom presentation with the New York C.S. Lewis Society on some of my discoveries with Lewis’s handwriting in September. A Zoom presentation for the Urbana Theological Seminary Tolkien Conference later in September. A pair of keynote addresses on “Remembering the Signs” from The Silver Chair to be given at the Lewis Foundation Camp Allen (Texas Retreat) in October, followed by a weeklong visit to the Wade Center which will include a presentation on Lewis’s handwriting.

As for non-fiction writing: I always have ideas for another book or essay about C.S. Lewis. I’ve submitted an essay on the relationship/friendship between Lewis and Tolkien for a book on Lewis and Men. I’ve been asked to write a chapter for a Routledge Companion to C.S. Lewis on the Ransom trilogy. I’m working with a small but international group of Lewis scholars on what we’re calling the C.S. Lewis Correspondence Project, in which we are hoping to publish some 300 Lewis letters which do not appear in Hooper’s three-volume Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis. I’m working on a long-term project which involves dating all the annotations in C.S. Lewis’s personal books. There are some podcasts and videos in the works for the future.

But here’s something I’m immediately excited about: GlossaHouse publishers will be releasing three of my out-of-print books very soon. They’ve all been revised and two will come out under new titles with some substantial changes. My illustrated children’s fantasy, King Lesserlight’s Crown, may already be out when this article is published. Two Bible studies I’ve written, Even the Hero: Christian Basics from Romans 1-8 and Sacred Screaming: What to Do When Your Problem is God will also be released this fall.

GlossaHouse may become home for other projects as well. I’m considering asking them to consider publishing a collection of essays, a collection of short stories, and a collection of poetry.

Charlie W. Starr’s books are available on Amazon and other major book retailers. To find out about his first three books as they go back into print, check out GlossaHouse Publisher’s website. Potential beta readers can contact him via his Facebook page.

You can hear Starr’s recent thoughts on Inklings topics at the Lesser-Known Lewis Podcast, Pints with Jack, and All About Jack. Information about future podcasts or interviews can be found on his Facebook page.

Interviewer’s Note: a link to the new GlossaHouse editions of King Lesserlight’s Crown was added to this article after original publication.

1 thought on “Inklings Scholar Interview: Charlie W. Starr”