Owen Barfield is a curiously underrated thinker. He was a lifelong friend of C.S. Lewis, who dedicated The Allegory of Love to Barfield, calling him “wisest and best of my unofficial teachers.” Lewis dedicated The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe to Barfield’s daughter Lucy and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader to Barfield’s son Geoffrey.

While Barfield didn’t attend many Inklings meetings—unlike the main group, he lived in London, working as a lawyer—he influenced multiple Inklings’ works. Charles Williams explored various ideas that resonate with anthroposophy, the philosophy that Barfield spent his life exploring. Stephen Medcalf and others have considered how Barfield’s philosophy of language influenced J.R.R. Tolkien’s writings. Outside the Inklings, Barfield’s work gained appreciation from writers like T.S. Eliot, Saul Bellow, and Walter de la Mare.

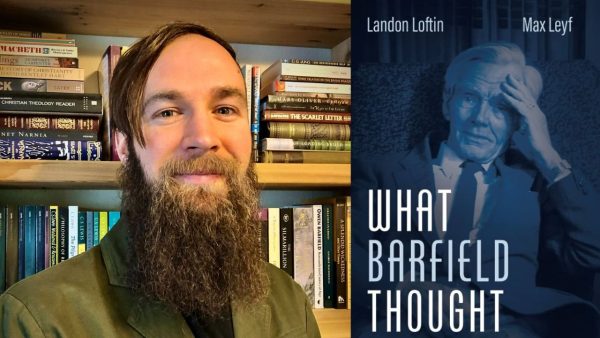

Despite writing quite a lot—including fantasy, science fiction, philosophy, and comedy—Barfield has had a much smaller audience than the big two Inklings. What Barfield Thought, a new book by Landon Loftin and Max Leyf released by Cascade Books, looks to rectify that situation. The title is an homage to Barfield’s 1971 study What Coleridge Thought.

Loftin serves on the Humanities Faculty of Gravitas: A Global Extension of the Stony Brook School. His other writings about Owen Barfield have appeared in VII, Journal of Inklings Studies, and The Lamp-Post. He was kind enough to answer a few questions.

Interview Questions

How did you first become interested in Owen Barfield?

Several years ago, I wrote a masters thesis on C.S. Lewis’ understanding of the role of the imagination in Christian theology and apologetics with particular reference to C.S. Lewis. In the course of my research, I realized that Lewis’ views about the nature and function of the imagination were forged in the fire of arguments he had with his friend Owen Barfield. I was reluctant to read Barfield because I had heard that his books were dense and difficult, but it didn’t take me long to realize that the difficulty had been exaggerated, and that, though reading Barfield does require a considerable investment of time and energy, it’s an investment that yields an extraordinary return.

How did you meet your co-writer, Max Leyf?

Owen A. Barfield (Barfield’s grandson and trustee of his literary estate) sent Max and I an email “introducing” us, since we were both engaged in research about Barfield. At that time, Max had just published an excellent study called The Redemption of Thinking, which deals with some of Barfield’s most difficult ideas. Since Max seemed to have a good understanding of the aspects of Barfield’s thought that remained murky in my own mind, I reached out to him after deciding to embark on an introduction and he graciously agreed to write it with me.

How long did this book take from the first draft to final publication?

We both came well-prepared to the project, so it did not take as long as I expected; once we had an outline and began writing in earnest, the manuscript came together in about 7 months.

You take time to thank many people in the preface, including Owen A. Barfield. What were some ways that he supported this work?

Well, as I mentioned earlier, he introduced Max and I. He also read the manuscript and provided some helpful feedback. But the biggest debt that we owe to him— indeed, the enormous debt that everyone who is interested in Barfield owes to him— is for the work he has done to ensure that most of his grandfather’s writings are easily accessible, either in print or online.

You’ve picked an unusual challenge by writing about Barfield. He’s been described as challenging to read, and he devoted his life to explaining a challenging writer, Rudolf Steiner. What were some of the biggest challenges to summarizing Barfield’s work?

Barfield is certainly difficult, but prospective readers should not be overly intimidated. The difficulty arises from Barfield’s insistence on questioning our most basic assumptions and interrupting common and deeply-set habits of thought. But he was a clear thinker and a skilled writer so, while he demands a lot from his readers, he also does as much as we can expect an author to do to help his readers along.

That said, we did not try to summarize Barfied’s work as a whole. Rather, our purpose was to explore the one big idea behind most of Barfield’s literary and philosophical endeavors: that is, “the evolution of consciousness.” Briefly (and inadequately) Barfield believed that the relationship between the human mind and the material world has been changing over the course of history. One result of this is that people in prior ages not only had different thoughts, but also a fundamentally different way of thinking, or form of consciousness, than modern people do. Insofar as we fail to recognize this, we are bound to misunderstand and improperly evaluate ancient philosophy, literature, art, etc. And insofar as we misunderstand and unfairly evaluate the past, we make ourselves prone to “chronological snobbery.” The challenge we faced in expounding this idea was the same that Barfield faced, which is that, in order to grasp it, readers must not only learn something new, but “unlearn” the habits of thought that keep us from entering into, and therefore understanding, other, usually older, forms of human consciousness.

The book’s first chapter suggests that it might be best to call Barfield not “central but foundational to the Inklings.” Can you elaborate on that?

Yes, Barfield is sometimes thought to have been on the periphery of the circle of writers known as the Oxford Inklings. And in one sense that is true: he and C.S. Lewis were very close, but due to circumstances, Barfield was not a regular attendee at Inklings meetings, and, by his own account, did not know all its members well. Nevertheless, I think R.J. Reilly was right in saying that “many of the romantic notions common to the members of the group exist in their most basic and radical form in [Barfield’s] work.” That, in short, is why we say that Barfield’s thought is foundational to the common spirit and ongoing legacy of the Inklings.

Western culture has gotten more than a little polarized in recent years. Do you think Barfield’s friendship with Lewis—Lewis calling him “the second friend” who has many opposing views yet remains a friend—has lessons we need to retrieve today?

Certainly. I never tire of reading accounts of Lewis and Barfield’s friendship, which was strengthened rather than inhibited by their disagreements. They both found intellectual expression for the joie de guerre in each other’s company, and I think many contemporary readers are delighted with the records of their arguments because our culture doesn’t provide a natural space for that kind of serious, no-holds-barred conversation; conversation that is at once highly competitive and fundamentally cooperative. As far as I am concerned, nothing is more invigorating than a good old-fashioned intellectual row in which every honest person walks away with bruised egos, sharper arguments and greater understanding of opposing views. Barfield and Lewis clearly understood the value of such things, and so do many of their admirers.

The book provides some thoughts on how Barfield’s ideas about language influenced Tolkien’s writing. Are there any Tolkien-Barfield connections you’d like to see future scholars explore?

I’m not sure about specific connections that need scholarly attention. I would, however, like to see more Tolkien scholars take the study of Barfield seriously. There is just enough evidence of influence to suggest something that is richly confirmed in the experience of people who are well-acquainted with the work of both authors, which is that, in certain important respects, there is a deep affinity between the minds of both men. I have been reading and rereading Tolkien since childhood, but I feel now, after carefully studying Barfield, that there are depths of Tolkien’s genius that I did not (and indeed, could not) have appreciated before.

Some time ago, I spoke with a Barfield expert who suggested American Christians have been reluctant to explore Barfield because of his anthroposophical beliefs. Does someone necessarily need to study anthroposophy to understand Barfield’s worldview?

Any serious, academic study of Barfield requires that attention be paid to Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. But you need not understand (much less accept) Steiner’s teachings in order to understand and profit from Barfield’s books. In fact, one conviction that we express in the introduction to our book is that Barfield should be treated as a profound and independent thinker in his own right. He is far too original to be read simply as an advocate of anthroposophy (or, for that matter, as a representative of the Inklings).

Potential readers who harbor reservations about Barfield’s anthroposophical beliefs should consider the great number of people who have at once explicitly rejected anthroposophy and yet heartily recommended Barfield. Lewis is the most obvious example, but many others could be listed. Interestingly, though Max and I are equally keen on Barfield, he is an anthroposophist and I am decidedly not.

One passage that struck me is chapter 4, about Barfield having great insights but “the profundity is liable to escape the distracted reader.” Given that so many of us are becoming more distracted readers thanks to digital tech, what are some ways we can prepare for reading Barfield?

Readers who are not willing to wrestle long and hard with Barfield’s ideas may as well not read him. I do not say that to discourage potential readers, but rather to encourage them to give his work the attention it deserves. Moreover, this is not because Barfield’s writing is verbose or obscure (as it is sometimes reported to be). Indeed, he was a skilled writer, capable of rendering even the most difficult ideas in lucid prose. The real difficulty, as I mentioned earlier, is a consequence of the fact that Barfield spends much of his time challenging our most basic assumptions and interrupting our most deeply-ingrained habits of thought. If we approach him carefully and receptively, he can not only form our thoughts, but transform our thinking (to use a distinction that Barfield himself was in the habit of making).

The book ends on a very inspiring note, declaring that a reappraisal of Barfield’s work is still on the horizon. What are some factors that make you especially hopeful about the future of Barfield scholarship?

Many devotees of Barfield have noted a resurgence of interest in his work. This is in part, I think, because the passing of time seems to continually reaffirm the prescience of Barfield’s message. One challenge that faces people who would enter the world of Barfield scholarship is that the body of secondary literature on Barfield is surprisingly small. But this also means that there are a lot of exciting opportunities available for people who wish to contribute to our understanding of Barfield’s thought.

What Barfield Thought is available through all major bookstore outlets. To learn more about the book, check out Mark Vernon’s interview with Landon Loftin and Max Leyf.

To hear more of Loftin’s thoughts on Owen Barfield, check out his appearances on the podcasts Poets & Philosophers and Pints with Jack.