Interviewer’s Note: Unless otherwise noted, all quotes in this profile are taken from an interview with Owen A. Barfiled on September 13, 2022. The only grandson of Inkling Owen Barfield, he is the trustee of the Owen Barfield Literary Estate and an important contributor to Barfield scholarship efforts. Other matrerial from the interview, related to Inkling Charles Williams, has appeared on The Oddest Inkling.

A Book for a Goddaughter

My Dear Lucy,

I wrote this story for you, but when I began it I had not realized that girls grow quicker than books. As a result you are already too old for fairy tales, and by the time it is printed and bound you will be older still. But some day you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again. You can then take it down from some upper shelf, dust it, and tell me what you think of it. I shall probably be too deaf, and too old to understand, a word you say, but I shall still be

Your affectionate Godfather,

C.S. Lewis

So reads the dedication to The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, the first published book of the Chronicles of Narnia. The Lucy in question was Lucy Barfield, daughter of Owen Barfield. Barfield met Lewis when they were both students at Oxford University, and they became lifelong friends.

Barfield published his first book, the fairy tale The Silver Trumpet, in 1926, making him the first Inkling to become a published author. After publishing two nonfiction studies (Poetic Diction and History in English Words) before he had turned 31, Barfield spent his professional career as a lawyer, including managing Lewis’ Agape Fund, which gave away most of Lewis’ book royalties to charity. Barfield began publishing again in the 1940s and after retiring from law, he became a visiting scholar at various American universities. When Barfield died in 1997, he was 99 years old and the last living major Inkling (minor member Colin Graham Hardie outlived him by 10 months).

Despite Barfield’s well-established influence on the Inklings (Tolkien and Lewis were both particularly influenced by Poetic Diction) and the fact he can be called “The First and Last Inkling,” he’s not very well-known. Owen A. Barfield, his only grandson (hereafter referred to as Owen for clarity), recalls talking with a Lewis expert and learning there are 10,000 books on Lewis. Owen estimates there are currently 12 books on Barfield.

As a result, many people don’t know much about Barfield’s children—Alexander, Lucy, and Geoffrey. Other Inklings’ children have been mentioned in biographies, written their memoirs, or become semi-fictional characters in biopics like Shadowlands. Lucy Barfield’s story is so little-known that in 2016, actress Lucy Grace delivered a one-woman show at the Edinburgh Festival about her love of Narnia and Grace’s journey to learn Lucy Barfield’s story.

Lucy Barfield passed away in 2003. Owen knew Lucy well and has written about her in the past—including a 2010 article co-written with Adelene Barfield, published in VII.

Since Lewis not only dedicated the first Narnia book to Lucy but featured a character named Lucy Pevensie, many have wondered if she inspired the character. The Owen Barfield Literary Estate website observes, “The character of Lucy Pevensie appears to be based in part on Lucy herself, sharing her name, fair hair, and lively personality.” During our interview, Owen affirms a point made in the VII article that he’s not convinced any one person inspired Lucy Pevensie. What matters more to him is that the book was a unique gift.

“I think Lewis and Grandfather identified her as a young person as being an extraordinary, gifted person,” he said. “And Lewis, of course, was her godfather. So, I don’t feel it’s so much that Lewis was inspired by her. I felt that Lewis wanted to do something for her as a child, which was to write the Narnia book for her and dedicate it to her. I feel there was a real personal connection with that child by Lewis, who was writing the book for her.”

Lucy’s giftedness (which will be discussed in detail later) extended to many artistic areas. Owen feels it also influenced his grandfather in important ways.

“Grandfather himself learned from Lucy, and I think his conversion to Anglicanism was following Lucy,” Owen says. “He decided to do that when he witnessed, and it was a testament to, Lucy being confirmed in St. Paul’s Cathedral in the City of London.”

Whether or not Lucy Barfield inspired the Narnian character, both are extraordinary individuals. Owen argues the name itself speaks to something extraordinary that many readers miss.

“The name Lucy, of course, is a very big clue, but the name Lucy is also very pregnant with meaning because it stands for the English spirit,” Owen says. “As Grandfather and the Inklings understood it—and this comes from Wordsworth, and then through Coleridge a little bit, in that world of Romanticism—Lucy stands for the English spirit. It’s shorthand for the guiding spirit of the English. And the Inklings, they were really fostering and lived the English spirit, that’s one of the things they brought to the world. They were extending the spirit of this small place called England into the world. Now, the phenomena—the spread of the English language, the interest in the Inklings, it’s a worldwide phenomenon—what’s at the root of that is a kind of English spirit. Which was identified even before the Inklings, but the Inklings knew it was something that was real. They could experience it, they knew it was happening, and they worked on that assumption. So, Lucy personifies that English spirit.”

Many readers would agree there is something saintlike about Lucy Pevensie, particularly given that she’s the Pevensie with the strongest connection to Aslan. In fact, sainthood may be the perfect term.

“Even the name Narnia has a connection to Lucy because C.S. Lewis would have started with the name Lucy, that’s his starting point,” Owen says. “Like these people always do, they always look up things in reference books—because there weren’t any computers, so they had reference books. And if you’d looked up Lucy in a book of saints, you would have found a kind of obscure lesser-known saint, Lucy of Narnia, which I think would have resonated with Lewis, and that’s where he got the name Narnia from. Starting with Lucy, and then you find Narnia is the place she is a blessed saint of.”

So, Lewis’ gift to Lucy Barfield proves to be a multifaceted one. A story dedicated to her where a character with her name is a Romanticist symbol, a saint, and probably the most beloved character by fans. Lewis could not have foreseen that this gift would become a much-needed bright spot in Lucy Barfield’s life, which changed radically within a year of Lewis’ death.

“Lucy had a tragic life,” Owen said. “In her late twenties—so that’s around 1963, 1964, something like that—she contracted multiple sclerosis. I don’t know how much you know about the disease of multiple sclerosis, but it’s a terribly debilitating disease. First, you’re incapacitated in your body, and then in your speech, and you can’t move.”

Lucy was officially diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) in 1966 and began using a wheelchair. For the rest of her life, she alternated between assisted housing, hospitals, and briefly lived independently with her husband, Bevan Rake.

A 2015 study reported that while MS patients’ life expectancy has improved since the mid-1980s, most patients today live an average of seven years less than the regular population. Furthermore, the relative risk of death is highest in younger patients. Lucy Barfield’s condition worsened to the point that doctors were shocked when she lived into her sixties.

“She just progressively went downhill, downhill, downhill,” Owen recalls. “But she lived 40 years like that, and she confounded all the doctors. Every year they said, ‘this will be her last year. She can’t live any longer, can’t live any longer.’ So, her vital force, her life force, was incredibly powerful, but her physical body was absolutely destroyed. And it’s just so sad.”

The VII article details a few bright spots in those 40 years. She met Bevan while she was a patient at the Royal London Homoeopathic Hospital (now the Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine); they married in 1978 (29). When Lucy’s symptoms advanced to the point she could no longer read, her brother Geoffrey (to whom The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is dedicated) read the Chronicles of Narnia to her (31).

During our interview, Owen remembers other family visits over the years. “My father went to visit her weekly, and I’d go maybe once a term or something like that. She was in hospital for 20 years solidly.”

By the time Bevan passed away in 1990, Lucy was already a patient at the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability in London. She stayed there until her death. The VII article notes that “for the last ten [sic] years of her life she was unable to move, speak, or feed herself” (30).

Any debilitating illness is a tragedy. However, it feels even worse when the individual seems on the cusp of extraordinary things.

“The tragedy was that she was so promising,” Owen says. “She was a music teacher. She was a poetess. She was a painter. Her paintings, watercolors, and poetry samples are on the website and in the Wade Collection. She was a ballet teacher, and she was a musician. She’d composed a symphony, which was played at Malvern College, which was C.S. Lewis’ old school. So, she was an incredibly gifted artistic person, and then in her twenties, she got this terrible disease.”

Despite her condition, Lucy carried great faith and love for life. Owen sees her faith as something she may not have always spoken about but clearly showed. It may have even been a faith refined by her circumstances.

“There’s a huge kind of spiritual dimension to being that disconnected to the material world, if you like,” Owen says. “It’s like being in an extreme form of retreat. So, she only had a spiritual life. But this was not something she could talk about or communicate easily because, in a hospital setting, you just can’t. An extraordinary person.”

All these details make Lucy a surprising and inspiring figure to remember. They also raise a question: how did Lucy feel about the Chronicles of Narnia? Owen believes the answer is that Lewis’ books became an even greater gift as time passed.

“I think because from her late twenties, or mid-thirties at least, she was so incapacitated, all she had—she had no family beyond us, there was nothing there to her life—all she had, the only identity she had, was the identity of Narnia that Lewis gave her,” Owen says. “So, Lewis gave her a gift that he had no way of knowing how important that gift was. Imagine you have multiple sclerosis. You are in a hospital bed. You cannot move. You cannot talk. You are fed through a straw. It’s a terrible condition to be in. The self-determining aspect of your own being, or what gives you an identity in your own right, is the fact that Lewis wrote this book for you.”

It’s estimated that Lucy Barfield was four years old when Lewis began writing The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe (Ford 101). She was 15 and healthy when it was finally published in 1950. When Lewis passed away in 1963, Lucy Barfield was 28 years old and showing symptoms of a disease that defined the rest of her life. But she still had his gift.

Notes for Researchers:

C.S. Lewis’ will, listing among other things, a sum he left to Lucy Barfield and his naming Owen Barfield and Cecil Harwood trustees of his literary estate, is available to read through the Discovery Institute.

For more on Lucy as a Romanticist symbol of the English spirit, see studies of Wordsworth’s Lucy poems and of Barfield’s novella Rose on the Ash-Heap.

Lucy Barfield’s poems and other papers are located at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College. Other Barfield family papers are located in the Owen Barfield Family Collection at Azusa Pacific University. More information is available through OwenBarfield.org, the Owen Barfield Society, or Simon Blaxland-de-Lange’s Owen Barfield: Romanticism Come of Age: A Biography.

Short profiles of the Inklings, major and minor members, can be found in “Who Were the Inklings Besides C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien?” by G. Connor Salter, published on Crosswalk.com.

Sources Cited

The dedication to Lucy Barfield is quoted from pg. vii of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. HarperTrophy, 2000.

Barfield, Owen and Adelene Barfield. “In Search of Lucy: The Life of Lucy Barfield, Goddaughter to C.S. Lewis.” VII: Journal of the Marion E. Wade Center, Vol. 27 (2010), 29-32. jstor.org/stable/45297219.

Ford, Paul F. A Companion to Narnia. HarperCollins, 2005.

Grace, Lucy. “The Lion, the Witch and the Goddaughter: the real Lucy behind CS Lewis’s classic.” The Guardian, August 1, 2016. theguardian.com/stage/2016/aug/01/lion-witch-lucy-lucy-and-lucy-barfield-edinburgh-festival-cs-lewis.

“Lucy Barfield and Narnia.” OwenBarfield.org, accessed October 29, 2010. owenbarfield.org/research/lucy-barfield-and-narnia/.

Blanchard, James and Michael Cossoy, Lawrence Elliot, Ruth Ann Marrie, James Marriott, Stella Leung, Nancy Yu. “Effect of comorbidity on mortality in multiple sclerosis.” Neurology Jul 2015, 85 (3) 240-247. n.neurology.org/content/85/3/240.

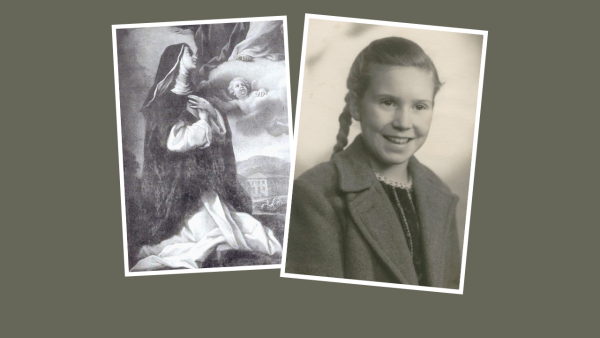

Cover Photo: Graphic of Lucy Barfield courtesy of the Owen Barfield Literary Estate. Painting of St. Lucy of Narnia is public domain painting by Etienne Parrocel.

1 thought on “Saint Lucy: Remembering C.S. Lewis’ Goddaughter”