Much thanks to Brenton Dickieson and Sørina Higgins, for inspiring and encouraging this piece.

Speculative fiction (fantasy, horror, science fiction, etc.) or spec fic has experienced many changes in the last generation. An especially shocking change for outsiders has been the fact comics have stopped being the genre’s least respected medium.

Spec fic novels (especially fantasy) started the slow march to respectability during the 1960s, thanks to the commercial boom created by Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Spec fic movies shifted from B-movie fare to respectable cinema in the 1970s, helped in large by Star Wars.1

Comics, however, were always at the bottom rung of respectability. Comic book publishing began in the 1890s as an efficient way to republish newspaper comic strips.2 Forty years later, Superman created the “golden age of comics,” but even then, comics were “the basement level of publishing” (Schwartz 106). It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that public perceptions shifted, and comics could be seen as literature. The shift laid the groundwork for modern-day academic discussions about comics and the current interest in serious superhero movies (the Dark Knight trilogy, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, etc.).

If you’re interested in how comics became considered literature, you’ll inevitably hear certain names. Will Eisner, who popularized the term “graphic novel” to market his book Contract with God. Art Spiegelman, who won a Pulitzer for Maus, an account of his parents surviving Auschwitz. Then there’s Alan Moore, who has generally been lauded as a genius.

A genius who has said he feels uncomfortable with comics’ legacy, but a genius in the field no less.

Who Is Alan Moore?

Explaining why Moore is considered a genius may require a full book (and there have been multiple written on him already).

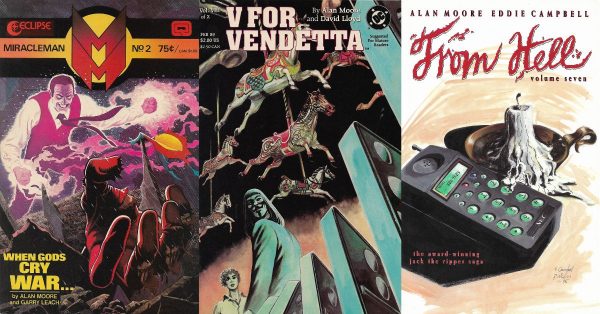

One key fact is his quick rise to the top. Moore’s professional comics career began in 1979, co-creating a character called Alex Pressbutton. Three years later, in 1982, Moore wrote two comics now considered classics: Miracleman and V for Vendetta. In Miracleman, Moore deconstructed a cheery 1950s hero into a ruthless, complex, godlike figure. V for Vendetta described a future England ruled by fascists, where an enigmatic figure wearing a Guy Fawkes mask topples the regime.

Two years later, in 1984, Moore reinvented a DC Comics character called Swamp Thing. In doing so, he helped create a trend of fantasy/horror DC comics with complex characters and mature material. Moore’s protégé, a journalist named Neil Gaiman who sought Moore’s advice on writing comics, solidified that trend with his epic The Sandman.

Two years later, in 1986, Moore worked on two seminal projects. The first was Superman. Moore had already shown Superman at his most vulnerable twice, in stories published in June and September 1985. In September 1986, Moore apparently killed Superman for good.3 The first issue of Moore’s story Watchmen went on sale the same month. Perhaps more than any of the decade’s graphic novels, Watchmen (a story about an alternate world where two superheroes protect America until one gets murdered and the other quits the human race) convinced mainstream readers that comics could be literature. It reinvented the genre.

By 1989, a decade into his professional career, Moore had finished his Miracleman saga and begun reinventing comics again. Instead of superheroes, he was writing about murder. The result, From Hell, is a retelling of Jack the Ripper’s Whitechapel murders featuring occult symbolism and time travel. It also has cameos from Ian Brady, William Blake, William Butler Yeats, William Morris, John “The Elephant Man” Merrick, Queen Victoria, and a teenage Aleister Crowley. From Hell won numerous awards, resetting the bar for what comics could be.

Given Moore’s considerable work, there are various angles to view his work. An interesting angle is that while Moore admits he is known “for creating dystopias,” he’s done more than that. He has created dystopias, utopias, and apocalypses. Miracleman begins as a deconstruction of superhero tropes, but Moore’s run ends with a utopian society built by superheroes. V for Vendetta is a dystopia that verbalizes ideas about freedom and authority Moore explored in Miracleman. From Hell turns the Whitechapel murders into an apocalyptic story transcending time and space. Each of these stories allows Moore a different venue for exploring certain themes—themes about liberty, oppression, and mythopoeia. To some extent, each plays with ideas Moore explored in his first superhero story, Captain Britain.

Although Moore doesn’t share the Inklings’ interest in Christianity, he taps into some similar ideas about myth and religion. Where appropriate, this discussion will consider how Moore’s exploration of myth and religion contrasts with their work.

The Beginning: Alan Moore’s Captain Britain

Moore began writing superheroes in 1982 when he became the writer on a series called Captain Britain. As Moore explains in the Captain Britain Omnibus, he got the job when the hero was halfway through a storyline that Moore “neither inaugurated nor completely understood” (viii).

Moore applied what became his signature when taking on an existing character: slash and burn. Captain Britain enters a battle, then he and his friends are ruthlessly killed. Then Merlin and his daughter take Captain Britain’s remains to their lab in space, resurrecting him before returning him to Earth. After Captain Britain sorts out his new life on Earth, he faces some old foes. Then he meets new foes: aliens who act like Doctor Who supporting characters written by Douglas Adams.4

After Captain Britain’s adventures with aliens are resolved, he returns to Earth to stop an old nemesis who has turned Britain into a fascist state.

Moore’s first superhero story is full of surprising ideas… perhaps too many surprising ideas cramped together. Multiple readers (including Tim Callahan and YouTuber Strange Brain Parts) have noted how Captain Britain contains ideas reused in Moore’s later projects. Fortunately, the later projects gave the ideas more room to breathe.

Miracleman, a reboot of a 1950s ripoff of an American superhero, proved to be a fertile ground for Moore to start exploring these ideas with more depth.

Return next week for Part 2 of Alan Moore’s Utopia, Dystopia, and Apocalypse.

Footnotes

1. As discussed elsewhere, 2001: A Space Odyssey was arguably the first big-budget prestigious sci-fi film, yet did not fare well critically or financially at the time. Star Wars had a much quicker impact—Alien, released two years after Star Wars, specifically got a larger budget after producers noticed Star Wars’ success.

2. As Roy Schwartz explains, comic book publishing started in 1897, often called the Platinum Age of Comics (182). Many Platinum Age comic books were reprints of newspaper comic strips, hence the period rarely gets mentioned. The Golden Age of Comics began in 1938 when the first Superman story appeared (ibid).

3. This two-part Superman story, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” was the last Superman story before DC Comics rebooted the character. Its story apparently follows Superman’s last days, a swansong for the character and the world that had accumulated around him over 50 years. Schwartz calls Moore’s story “a worthy, if bittersweet, coda to the classic Superman” (252).

4. According to Tor.com writer Tim Callahan, these alien mercenaries are in fact characters that Moore invented in 1980 for Doctor Who Monthly.

Print Resources

Claremont, Chris and Alan Moore, Jamie Delano, and Alan Davis. Captain Britain Omnibus. Marvel, 2009.

Moore, Alan. Superman: Whatever Happened to The Man of Tomorrow? The Deluxe Edition. DC Comics, 2009.

Schwartz, Roy. Is Superman Circumcised? The Complete Jewish History of the World’s Greatest Hero. McFarland & Co, 2021.

I should probably clarify this: when I say that fantasy began the slow motion to respectability in the 1960s, I mean that if you look at what Lin Carter and his colleagues are right in the 1960s, a lot of it is attempts to renovate the genres reputation and show that fantasy more than just kids stuff. CS Lewis discusses anti-fantasy bias in several essays collected in his book of other worlds, written in the 1940s-60s. JRR tlTolkien’s essay “Beowulf: monster or critics” can be seen as an attempt to justify reading it as a good fantasy story as well as a historical artifact. You see similar efforts by George MacDonald in at least one essay about whether fairy tales need to have a clear moral to be considered worth reading. So yes, there were people before in the 1960s who treated fantasy as serious literature. However, there was a broad assumption at least in popular culture that fantasy shouldn’t be taking that seriously.