Click here to read the previous installment.

An Apocalypse of Cockatoos: From Hell

From Hell feels in many ways like a departure from Alan Moore’s prior work. It isn’t a superhero story like Miracleman, Captain Britain, or Watchmen. Nor is it a vigilante story like V for Vendetta. However, as with these earlier works discussed in this series, it may be seen as Moore reconsidering past ideas.

Once again, he explores an idea he had explored briefly in Captain Britain.1 Like Captain Britain, this story is an apocalypse. Moore’s opening to Captain Britain (the hero and his friends being killed) is apocalyptic, even though the hero gets brought back from the dead shortly afterward. Captain Britain becomes apocalyptic again at the end, when Captain Britain takes down a fascist supervillain in a huge battle story titled Götterdämmerung.

A similar apocalyptic sense appears in Moore’s other 1980s works. Watchmen deconstructs superhero tropes while telling a story about superheroes trying to stop a nuclear war that could destroy the world. In Moore’s three Superman stories, the Man of Steel finds himself in situations where death or incapacitation seems inevitable… and without Superman around, who will save the world next time? The Swamp Thing and Miracleman experience miniature apocalypses: they learn that everything they know about themselves is wrong. The protagonist’s world crashes around his shoulders before rising again. So, Moore coming back to apocalypse in From Hell is not surprising.

What is surprising is how From Hell takes the apocalyptic tone in a new direction. A direction that goes to the root of what apocalyptic literature is.

Apocalypse… Now?

Apocalyptic literature is often associated with the end of days. However, even in Biblical studies, it isn’t just about the world ending. Writing in 1988, theologian Eugene Peterson argues that the Bible’s final book is ultimately about retelling the Gospel narrative in a new way.

“I do not read the Revelation to get additional information about the life of faith in Christ… Everything in the Revelation can be founded in the previous sixty-five books of the Bible… The truth of the gospel is already complete, revealed in Jesus Christ. There is nothing new to say on the subject. But there is a new way of saying it. I read the Revelation not to get more information but to revive my imagination.”

– Reversed Thunder, xi-xii

Even in sermons where Peterson described Revelation as being about the future (such as his 1984 sermons published as The Hallelujah Banquet), he maintained the apocalyptic text has as much to say about the present as it has to say about what is coming.

“The book of Revelation really is about the future, but what it says does not satisfy our curiosity or match what we think are the obvious things to say. It is not a disclosure of future events but the revelation of their inner meaning. It does not tell us what events are going to take place and the dates of their occurrence; it tells us what the meaning of those events is. It does not provide a timetable of history. It is not prediction but perception. It is, in short, about God as he is right now. It rips the veil off our vision and lets us see what is taking place.”

– The Hallelujah Banquet, 7

So, apocalyptic literature may not be a clear-cut vision of a coming disaster. It may be a lens for seeing the past or present in a new way. This is key for understanding From Hell, which Moore built around an idea that the Whitechapel murders of 1889 were an “apocalyptic summary of those times” (Groth 79).

The Apocalypse of Jack the Ripper

From Hell opens in London a year before the Whitechapel murders start. Following a conspiracy theory Stephen Knight suggested in his 1976 bestseller Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, Moore presents the killings as an elaborate assassination mission.

Women of ill repute living in Whitechapel try to blackmail Queen Victoria’s grandson over an illegitimate daughter. The daughter has disappeared. The mother has been committed to an asylum. Still, the threat remains potent.

Queen Victoria has already called on physician Dr. William Gull to silence her grandson’s paramour. She requests his services again. With streetwise cabbie Netley as his sidekick and Freemason brethren covering his tracks, Gull begins his bloody mission.

When Moore started writing From Hell in 1989, most “Ripperologists” had disowned Knight’s book. Moore freely admitted that he didn’t believe its claims and would not claim to identify Jack the Ripper.

“Slowly it dawns on me that despite the Gull theory’s obvious attractions, the idea of a solution, any solution, is inane. Murder isn’t like books. Murder, a human event located in both space and time, has an imaginary field completely unrestrained by either. It holds meaning, and shape, but no solution.”

– From Hell Appendix II: Dance of the Gull-Catchers, 16

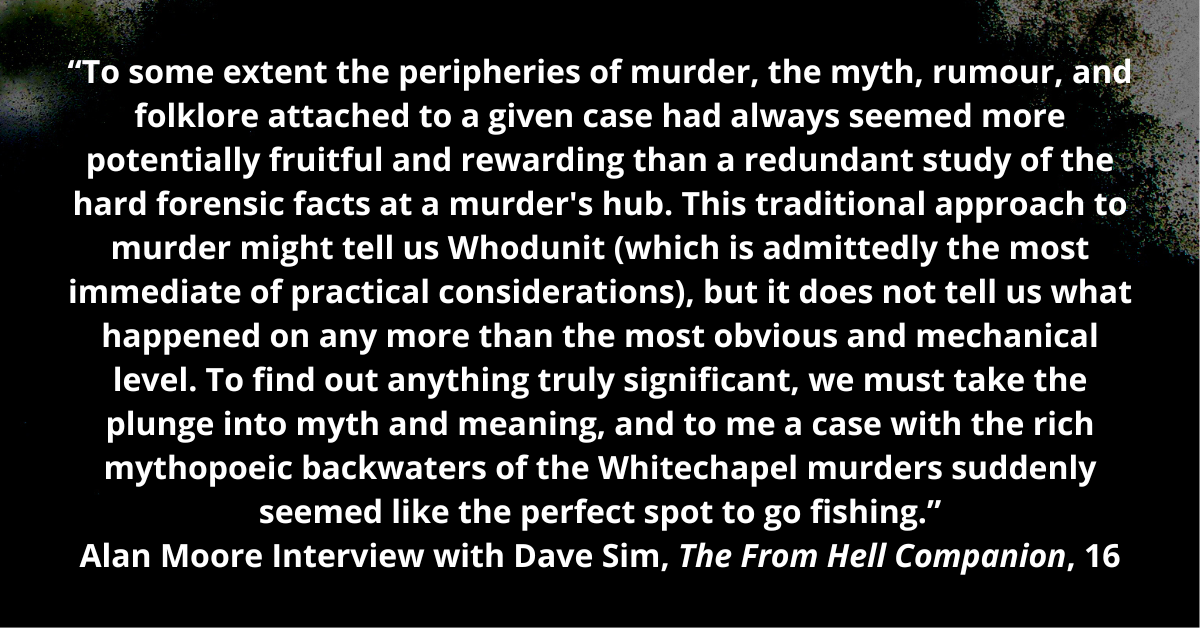

However, as Moore explained in a 1997 interview with Dave Sim, “there were still ways to approach the Whitechapel murders that might expose previously unexplored seams of meaning” (ibid). The true solution might be found, perhaps not. Regardless of who Jack the Ripper really was, a story about him could be a vehicle for other ideas.

As noted earlier, mythopoeic literature takes past elements to forge a new mythology. Moore had already experimented with the idea of multiple stories of one event, that myth-making may be more interesting than the clinical facts, at the end of his Miracleman saga. In From Hell, he avoids solving the Whitechapel murders but uses one of the many stories that have joined Jack the Ripper mythology, so he can say something new.

Apocalyptic Mythology

The idea of combining mythopoeia with apocalypse may sound bizarre, particular to readers who associate mythopoeic literature with books like The Lord of the Rings. However, one of Tolkien’s Inklings contemporaries provides a model for making a simultaneously mythopoeic and apocalyptic story. Perhaps not surprisingly, it is the Inkling who had the most in common with Moore: another gloriously inconsistent, charismatic yet mercurial, ferociously prolific man fascinated by the occult. I refer, of course, to Charles Williams.

Williams is best known today for writing supernatural thrillers like War in Heaven, but he also wrote thought-provoking Arthurian poetry. Brenton Dickieson outlines how in Williams’ poem “The Son of Lancelot,” the story of Lancelot fathering Galahad becomes more than a story about a knight falling from grace. Williams uses biblical imagery (comparing Lancelot to Nebuchadnezzar, comparing Galahad’s birth to the Revelation 12 nativity) to do what Jewish apocalyptic writings do: recast past events for a new perspective. For example, The Apocalypse of Abraham retells Abraham nearly sacrificing Isaac, shown in the context of Israel’s history, and then “Israel in terms of her entire mythological framework” (Dickieson 1).

In apocalyptic literature, “by the aid of a mediator, we are risen to a cosmic view so we can see the true significance of history through mythic-spiritual symbolism” (ibid). As Peterson would say, the main goal behind an apocalyptic work may not be showing the future, but contemplating the past in new ways.

In Williams’ poem, the apocalyptic tone provides a new way to understand how Arthur’s England is changing. Galahad’s birth marks a new age. He is not just Lancelot’s son; he is the messiah child who may rebirth Logres.

Hence, apocalypse can be a form of mythopoeia. It can recast older myths (Arthuriana) or historical events (Abraham sacrificing Isaac) in a new light. Moore accomplishes the latter in From Hell, turning the Whitechapel murders into an apocalyptic tale about misogyny, history, and authoritarianism.

Crimes with Cosmic Significance

Moore starts taking From Hell in an apocalyptic turn when Gull enters the story. He casts Gull as a man who has reached great heights. A respected Freemason. A surgeon whom Queen Victoria trusts to examine her family. A man with sophisticated friends—like James Hinton, who tells Gull about his son’s essays on the fourth dimension. Despite his prestige, Gull yearns for a “special task.” (From Hell Chapter 2, pg. 25).2 A stroke before Gull’s seventieth birthday, during which he sees Masonic deity “Jah-Bul-On” (From Hell Chapter 2, pg. 26), seems a harbinger of great things to come.

When Queen Victoria assigns Gull to deal with Mary Kelly and her friends, Gull treats this as his great task. He takes Netley on a trip around London to five locations that create a pentangle formation. He points out Masonic symbols in architecture and talks about magic. Gull describes his task as more than assassination. He views killing these women as an act of ceremonial magic to put down womenkind. To Gull, human civilization is a long story about women once ruling in prehistoric matriarchal societies, followed by men creating a masculine, rational world. Movements like the Suffragettes leaves Gull worrying that womankind is rearising. Steps must be taken.

“Measured against the span of goddesses, our male rebellion’s lately won, our new regime of rationality unfledged, precarious. Our grand symbolic magic chaining womankind thus must often be reinforced, carved deeper yet in history’s flesh, enduring ‘til the earth’s demise…”

– From Hell Chapter 4, pg. 25

Gull’s mission is bizarre. It becomes even more more bizarre as the fourth dimension Hinton told Gull about apparently breaks down. While preparing to kill his second victim, Gull looks into a window and sees a twentieth-century living room where a man watches TV (From Hell Chapter 7, pg. 24). While killing his final victim, Gull sees a vision of a modern office space, which he realizes must be the future.

As the office space vision fades and Gull returns to the room where his victim lies, he seems depressed. As he leaves, he tells Netley that things are “only just beginning. For better or worse, the twentieth century. I have delivered it” (From Hell Chapter 10, pg. 33). In the book’s final act, dying in an asylum, Gull has one last vision, where he sees future serial killers, including Ian Brady and the Yorkshire Ripper.

Moore leaves it ambiguous how authentic Gull’s visions are. The key is he uses them as one of several strategies to cast the killings in an apocalyptic light. As “The Apocalypse of Abraham” sets Abraham killing Isaac in a wider, cosmic context, Moore sets the Whitechapel murders in a wider social context (the cameos of Crowley, Yeats, etc., mentioned earliers) and a cosmic context (the shifts across time and place). Moore uses apocalypse to explore the Whitechapel murders from new angles.

Apocalypse As Social Critique and Warning

Moore brings many themes into his story about the Whitechapel murders, but three are especially worth noting.

1. Authoritarianism

A common thread running through Miracleman and V for Vendetta is freedom as liberty with few restraints—also a crucial theme for Moore’s life, since he politically identifies as an anarchist. Miracleman imagined a memorable but inconsistent utopia where such freedom can only happen if humanist superheroes become gods who keep the system going. V for Vendetta imagines an anarchist bringing down a dictatorship, encouraging people to embrace their ability to rule themselves individually. From Hell serves as a different critique of authoritarianism.

By using a theory that the Freemasons and Victoria were behind the Whitechapel murders, supporting the work without performing the killings themselves, Moore turns the killings into a discussion about how far authoritarians will go to protect themselves. Victoria wants the women eliminated to protect her legacy. The Freemasons want Victoria’s wishes fulfilled to keep their power system in place. Once the crimes end, Moore depicts the Freemasons going even further to hide Gull’s tracks.

Neither Victoria nor the Freemasons have the fascist imagery of Norsefire in V for Vendetta. However, as Elizabeth Ho observes, these Freemasons serving Victoria do resemble “Thatcher’s England… an old boy’s club [whose] primary goal is to protect its own and its iconic mother figure” (103). Moore depicts them as one step removed from the dystopian regime in V for Vendetta, yet another variety of authoritarians willingly crushing others for “the greater good.”

2. Misogyny

Moore’s apocalypse provides a new lens for considering misogyny in the Whitechapel murders. Gull declares he represents male authority, which he believes must dominate womenkind. Meanwhile, Gull’s victims are women already destroyed by circumstances. The detectives talk about how Whitechapel locals are “married by twelve, most of ‘em,” though marriages frequently end and the girls become prostitutes (From Hell Chapter 6, pg. 22). There are, as one of the detective notes, “twelve hundred tarts in Whitechapel. Officially.” (ibid).

All of Gull’s victims are (officially or not) prostitutes, barely making rent money. Mary Kelley decides to blackmail the Royal Family because she needs money fast after an extortion gang threatens her friend. These women live in an environment where selling one’s body and selling dirty secrets have become the only way to survive.

The society-wide misogyny is also underlined in how supporting characters behave. Victoria is portrayed as a woman who doesn’t mind crushing other women threatening her power. When her grandson mentions the Whitechapel murders to his friend J.K. Stephens, Stephens replies, “Oh Eddie! Come off it! They were women! They must have done something” (From Hell Chapter 8, pg. 8). Whether or not these historical figures are portrayed accurately, Moore uses them to highlight a particular point: this is a society where minimal opportunities, power dynamics, and systemic poverty leave few women with options. In that context, the Whitechapel murders become a symptom of misogyny infecting the whole society.

“It’s easy enough to say that From Hell depicts the infamous Whitechapel slayings of 1888 — the so-called Jack the Ripper murders — as a conspiracy theorist’s dream… But the novel goes further, implicating the violent misogyny of all of Victorian society, from Queen Victoria on down — and the misogyny of our own time.”

– Craig Fisher and Charles Hatfield, The From Hell Companion, 5

3. Future

Moore portrays the Whitechapel murders as a harbinger of doom, as one age transitions to the next. Unlike Williams’ “Son of Lancelot,” where the apocalypse involves a messiah child ushering in a potentially better age, From Hell involves an antichrist figure ushering in a darker age. Moore argues that the Whitechapel murders “embody the essence of the 1880s,” a decade that itself embodied the essence of the twentieth century (From Hell Appendix I, pg. 14).

Moore highlights various trends and events in the 1880s—scientific advancements like the light bulb, political trends like rising antisemitism—that had dark consequences in the twentieth century (ibid). He also highlights the curious fact that Adolf Hitler was conceived around the time the Whitechapel murders started. After Gull declares his mission to Netley, the story shifts briefly to Austria, where a woman implied to be Adolf Hitler’s mother has a vision of blood gushing from a church (From Hell Chapter 5, pg. 2). Doom is coming.

The shifts across time and space allow Moore to show the world that is coming (Gull sees a modern-day room with a TV, and later an office space). Gull looks around the office space and observes how impersonal this future world is.

“It would seem we are to suffer an apocalypse of cockatoos… Morose, barbaric children playing joyously with their unfathomable toys.”

– From Hell Chapter 10, pg. 21.

The technological advances of the 1880s will change the world. Gull’s actions will become part of the revolution.

Other details affirm that Gull’s violence forewarns what is coming. Mrs. Hitler’s vision of blood running through a building heralds the violence in Whitechapel and the antisemitic violence her son will wreak. Antisemitism figures in the Whitechapel case, with police trying to pin the killings on a Jewish leather worker. The future killers that Gull sees (the Yorkshire Ripper, Ian Brady, etc.) will carry on his example in terrible ways. In playing the Whitechapel murders as “The Apocalypse of Jack the Ripper,” Moore forces readers to consider how that period foreshadowed and helped create the violent world we know.

Moore As Mythmaker

From Hell continues Moore’s interest in mythopoeia, seen in Miracleman and V for Vendetta, yet applied to new contexts. In doing so, Moore highlights particular elements of the Whitechapel murders (Victorian misogyny, corrupt hierarchies, violence forewarning future violence), recasting the story in a cosmic view to highlight those particular elements.

The fact that Miracleman, V for Vendetta, and From Hell all become critiques of authority shows how utopia, dystopia, and apocalypse can explore the same theme via different lenses. Utopia allows a writer to show a society with values they promote, without necessarily showing how they can be attained. Dystopia allows a writer to show what happens if a certain value is forgotten, often tying the story explicitly to its written period to provide a critique of the present. Apocalypse allows a writer to use osmic scale to show a society and its injustices, a broader critique with less topical references.

The fact that Moore uses utopia, dystopia, and apocalypse to explore similar themes in such very different ways shows that his talent is not overrated. His chosen themes—particularly his arguments for anarchy and free love—may not be as life-giving as he believes. Still, the ways that Moore explores his ideas are always interesting and definitely literary. Even at his most maverick and inconsistent, Moore has shown that comics can be literature and have a worthy part in the speculative fiction canon.

After decades of legal battles, Neil Gaiman will finish Miracleman: The Silver Age, the second phase in a three-part epic. New issues of Miracleman: The Silver Age are on sale. Alan Moore’s first novel, Voice of the Fire, has been reissued for its twenty-fifth anniversary.

Footnotes

1. Douglas Adams is a smaller touchstone in Captain Britain and From Hell. As noted earlier, Moore uses sci-fi elements in Captain Britain that resemble Adams’ work. While there’s nothing Adamsesque about the plot of From Hell, Moore said in a 2001 BBC interview with Danny Graydon that Adams inspired a key plot point: “I’d seen advertisements for Douglas Adams’ book ‘Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency.’ A holistic detective? You wouldn’t just have to solve the crime, you’d have to solve the entire world that that crime happened in. That was the twist that I needed.”

2. From Hell was first published in 16 volumes which each had a numbering system based on the chapter, as in “From Hell, Chapter X, pg. Y.” This numbering system was maintained in the collected volume, which also includes two appendices. All quote citations are from the collected volume, using its pagination system. For clarify chapters versus page numbers, “pg.” is put before page numbers for in-text citations.

Print Resources

Fischer, Craig and Charles Hatfield. “Foreword.” The From Hell Companion. Knockabout Comics & Top Shelf Productions, 2013, pg. 5.

Ho, Elizabeth. “Postimperial Landscapes ‘Psychogeography’ and Englishness in Alan Moore’s Graphic Novel ‘From Hell: A Melodrama in Sixteen Parts.’” Cultural Critique, no. 63, 2006, pp. 99–121, jstor.org/stable/4489248.

Moore, Alan and Eddie Campbell. From Hell. Top Shelf Productions, 2004.

—. The From Hell Companion. Knockabout Comics & Top Shelf Productions, 2013.

Peterson, Eugene H. Hallelujah Banquet: How the End of What We Were Reveals Who We Can Be. Waterbrook, 2021.

—. Reversed Thunder: The Revelation of John and the Praying Imagination. HarperOne, 1988.