In the Passion Narratives of the Four Gospels, the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, is not portrayed as a menacing monster or two-dimensional villain, but as the image of fallen mankind, made of flesh and blood and ambition, along with the underbelly of weakness that accompanies it. He becomes the cynical “every man”, representing each one of us, his fate caught on the swinging hinges of history. He speaks more often than not with accidental irony, only half-seeing what is happening in front of his very eyes. Indeed, his life as portrayed in legend might be seen as one great unfolding irony.

Apocrypha holds that he was born in Scotland beneath an ancient yew tree, a foreboding symbol of death. His mother was Caledonian tribeswoman who pleasured the Roman soldiers stationed at Fortnangall, and his father was an official of Caesar, who would go on to acknowledge the boy as his own and have him educated as a true Roman. He would have learned of the founding myth of his civilization, Romulus and Remus suckled by a she-wolf, and how Roman law and justice had brought order to a warring world and reached the pinnacle of human achievement.

And yet even though this noble blood flowing through his veins, he could not change the fact that he was of mix race, forever tainted, having come forth into the world the unwanted accident of a night’s folly, under a tree as twisted as the ways of men. Under such circumstances, he could afford to play the cynic. He would be a loner, a plodder, a self-made man. But in spite of all hurdles in my path, he would excel as a military officer through his father’s good name and his own determination and fight campaigns against barbarians to defend and expand the empire. And yet when he obtained the position as Governor of the province of Judea, he was expected to sheath my sword, and work to uphold Pax Romana in conquered lands.

Nevertheless, Pilate did not suffer fools, or rebels, lightly. If any Jew dared raised his hand against Rome, that hand would be swiftly cut off. He was not afraid of the use of manacles and whips and crosses. He gained whatever power he could snatch at, and intended to hold onto it. He claimed his security from his worldly rank, but a chance encounter with a prisoner brought before him for judgment slowly but surely crumbles this pretension and reveals it, cover a deeper personal insecurity. The prisoner’s name is Jesus, the son of a carpenter turned itinerant preacher, who dared to challenge the supremacy of the Temple leaders.

Perhaps he takes some mild satisfaction in Jesus causing a stir among the Sanhedrin, even turning the tables over on them earlier that week. Of course, too much unrest might be dangerous for Roman interests, and it is better to deal with those who power who bowed to their imperial overlords. But he still has little love for the Sanhedrin, and hates the idea of being mired in one of their jealous schemes. He senses Caiaphas is using him to eliminate religious rivals. He feels this type of petty plotting by hierarchical hypocrites of a conquered people is beneath his self-respect. He wants no part with it. He wants a way out.

What must Pilate have thought when he first looked into the eyes of Christ? Perhaps he himself did not fully know, perhaps he tells himself that he, unlike the simple-minded Judean peasantry, is immune from it. But it is pulling at something deeper still within the man: his humanity, his soul, his consciousness, his underlying unease when confronted with things beyond the norm, things that whisper numinous mysteries. He thrived on the order of his universe, and that stability is going to be shaken. For all his years of bloody soldiering iron-fisted edicts, something here gives him pause, something halts him. Though he has mixed rebel blood with mortar often enough in the name of the empire, some inner instinct, and some vulnerable point of his heart, does not want this man’s blood to stain his hands. All is not as it seems.

Perhaps he had heard other rumors about the Nazarene, how He is credited with curing all manner of disease, casting out demons, commanding the elements, and turning back death itself. But most telling of all is His supposed power to read men’s souls, so that the thoughts of their hearts would be laid bare. He has been known to convict those He has encountered with a mere word, a glance. He brings out the worst and best in humanity by His very presence.

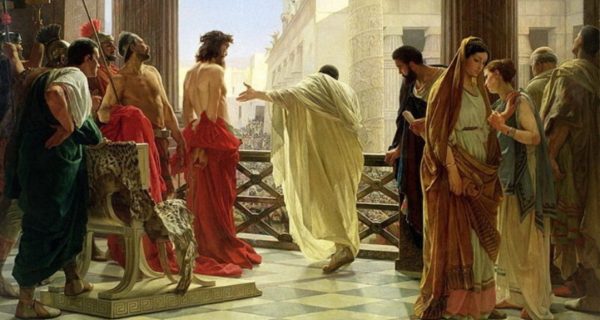

So Pilate interrogates him, asks if there is truth in the charge that He claims to be a king. Christ answers a question with a question, asking if Pilate asks it of His own accord. Even now, it seems, He is sifting the souls before Him, and holding them in the balance. The cat-and-mouse game continues, with the Nazarene giving veiled answers or silence in response to the questions put to Him. But one thing is clear from Him: He says His kingdom is not of this world, for if it were His followers would be fighting to free Him. Indeed, this is the most important point for Pilate, whose duty is to suppress claimants to temporal power.

Then the governor’s wife Claudia sends him a message, telling him of dream she had about this Rabbi from Galilee the night before, and her insistence that her husband have nothing to do with the case against Him. Her presence alongside him in Palestine, where there were genuine risks to run, indicates some genuine devotion, and for her to assume he would take her advice indicates she may well have been a helpmate and counselor to Pilate. Besides that, dreams were held to be portents of the future and omens of doom among Romans, sent from the gods or ancestors to grant a glimpse of things to come. Was the chanting of Pilate’s name in the Credo one of things she heard? Would their bond be close enough to alter destiny, to alter eternity?

In his half-sight through a dim glass, Pilate failed to realize that the Man before him was the Heart-beat of all mankind that would soon be pierced, and that anything he had done to the least other man, he had already done unto Him. And yet even with his blurred vision, Christ has almost become a manifestation of his conscience that he is afraid to face yet also afraid to kill, lest he lose himself altogether. Whether or not he believed in the gods as anything more than vague representations of ideals, or statues embroidering the past of his people, he was a Roman, and Rome prided herself on her justice. It was his race that had coined the maxim “Fiat Justitia ruat caelum” – “Let Justice be done, though the heavens may fall.”

But as the long Friday morning wore on, it must have felt as if they were falling on him. Yes, heaven really was falling, straight into the pits of hell, and ever mortal found themselves standing somewhere in the chasm, the great betwixt and between of light and darkness. But Pilate still searched for a way out, so sends his prisoner off to the puppet king Herod for judgment. Herod mocked the “magician” of Galilee, but sent him back to Pilate without resolution being reached. By now, the Chief Priests have gathered together a crowd in the courtyard to demand the death penalty for the Nazarene. Pilate goes on to offer them a choice between releasing this man and a murderer named Barabbas, in hopes of swaying the crowd. But they will not be swayed…they will free the guilty over the innocent.

In desperation, Pilate will give away his moral high ground and orders Christ flogged. He knew the nature of these things; whips with bits of metal attached, a partial death sentence as it was. But perhaps it might put an end to the horror. Perhaps he thought this compromise with corruption may be enough to get away mostly clean. Was it that the more Pilate tried to save this man, the more invested in his life he became? And the more that he put questions to Him in their strange cat-and-mouse game, did it became more uncertain who was the cat, and who was the mouse? The High Priests have said this Man claims to be the Son of God. But what god? No Roman god, surely. Why should Pilate care about the son of some Jewish deity, a pitiful one at that, drenched in blood, with a twisted branch of thorns for a crown?

Yet still he is disturbed by the implications, and demands where Jesus has come from. “For this I came…to bear witness to the Truth,” Christ told Pilate. “He who is of the Truth listens to my voice.” And Pilate the cynic queries “Quid est veritas? What is truth?” He would not have thought, then, of the anagram of the phrase: est vir qui adest, “it is the man who is here.” Yes, the man who is here, who is front of you, always, and in every innocent victim and vulnerable outcast, in everyone and everything from whom we choose to turn away. Yes, yes, the Man is still here, still bleeding, still being turned over to a howling mob crying out to crucify him, crucify him, crucify him…

Now the time of judgment has come, of men over Man and more than that, of God over men, and men over God. Peering down from the steps of judgment, across the faces in the crowd, Pilate might have thought one last time upon this prisoner, and how he feel stripped naked before him, pulling at the better angels of his twisted nature, and of our twisted nature. Was the yew tree so very different than the fruit tree, at the end of the day? And was the Hound of Heaven baying in Pilate’s own heart, louder than he could ever have wished? Perhaps all he knew was himself, and the Man, as if we were the only two beings beyond the insanity raging below.

But there is no justice in this world, he decides. The gods are made of stone, images of ideals no mere mortals can hope to achieve. Why should the heavens fall on his head? Why should he sacrifice himself for lofty notions thought up by philosophers? Life is too short, with too little meaning. He must grasp what we can, while time is still on his side. What does it matter to him if there be one god, or a thousand, or none at all? And so Pilate is both condemner and condemned in this, and so is everyone in the crowd. Indeed for him, the spirit had been willing, but the flesh had been weak, and so he washes his hands in water that can never clean the soul, even as he suffers the Living Water to be spilt in the Jerusalem streets.

“Ecce Homo!” he cried before the crowds. “Behold the Man!”

Yes, Ecce Agnus Dei, behold Him, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, and finds Himself alienated from both God and Men. Yes, behold Mankind, baying for blood below, behold them for whom this blood is shed, trickling down through the sands of time, wet and weary, coagulating with crime upon crime and ever darkening blindness that swallows up the very senses of the soul. And yes, behold this man who casts judgment now, this “every man”, this mirror of our best intentions and worst results. Behold Pilate, and know we stand in his place and utter his words of condemnation upon our King.

He could not know that his verdict that day would seal the fate of Rome and shake it to its foundations. He could not know that his language, stately, solemn Latin, will become the universal liturgical tongue to adore this Man he condemns, to call for “Ubi Caritas” among the members of the Body of Christ and sing “Salve” to his grief-stricken mother who may well be somewhere in that crowd, leaning against the beloved disciple for support. He could not know his name would forever be repeated in the mass, spoken daily by billions of Christians throughout the world as the one who made God Himself suffer in the flesh, even as that same Flesh and Blood is held up before the altars.

Will Pilate feel death forever gnawing at him until his own knife claims his own life in a prison cell years later, after finally encountering and being overcome by his greatest fear, the loss of power, of position? He could at least die stoically like a man, he must have thought then. Perhaps that would cheat his enemies of the sweetness of mockery, of deriding Pilate, wasting away in a dungeon. His sullied honor would be restored to some extent, through my own self-destruction. But did his hand tremble on the blade? What a strange thing it is, to harm one’s self! So unnatural to man, with his wit and cunning and ambition…oh, ambition…

Would he then see again the eyes he saw for the last time as the cross was on His bloodied back, which surely show not hatred, but pity? For in truth, if there be any truth at all, Christ knew Pilate, and not just like a pagan god, dictating fate without entering into the mystery of humanity…no, he knew Pilate more than Pilate knew himself. For though the high priests would not be contaminated by going under Pilate’s roof, Christ had been brought there, and He had offered to go to a centurion’s house once before, on a mission of healing. Who is to say he might not have come under Pilate’s roof, deep within himself, on just such a mission when the end came? Who is to say that the blood on his hands might not have been the blood of his salvation?