Susan awoke in her own bed in confusion. She didn’t remember falling asleep, and she didn’t feel as if she’d slept, though she knew she’d just opened her eyes.

The sun mocked her disarray, glaring at her through her window. Susan tried to shift, but her dress tangled around her legs—the same dress she’d worn to the Bryant’s New Year’s party. The waist belt pinched at stomach and the material she once thought was lovely now itched miserably at her skin.

Susan’s eyelashes were heavy with tears, and her eyes were sore and swollen.

Then Susan remembered. Susan Pevensie’s entire family was all dead and she was all alone. Except for Carl.

He must have been the one that brought her to her home and bed, too overcome with grief to have been aware of any of it. She had to see him—maybe ring for him, or something. To at least thank him. But she wished he might come. She couldn’t be alone. Not now.

Susan forced herself out of bed. And then she forced herself to change into a more comfortable day dress.

Outside of her room she ran into the Mrs Taylor, who was sniffling over a pile of laundry. The maid wiped her eyes as soon as she saw Susan. She spoke in a soft voice, “How are you, miss?”

Susan tried to answer, but she couldn’t. So she changed the topic. “You shouldn’t be working today. It’s Sunday morning.”

The maid laughed, “It is, isn’t it? The days are all muddled in my mind.”

Susan felt something she hadn’t truly felt since her childhood days—empathy. She reached toward the woman and squeezed her hands. “Why don’t you take the week off? I’ll be fine.”

But Mrs Taylor shook her head. “I’ll finish this laundry and then go. But I will be back tomorrow. I won’t leave … I won’t leave you, miss.”

Susan wanted to argue, but she had no strength.

The maid picked up her basket of laundry and passed Susan, then stopped to say, “Your man is in the parlor, miss.”

“Oh, thank you.” Susan hurried down into the parlor but stopped when she saw that Carl lay asleep on the sofa, his hat balanced over his face. She couldn’t bring herself to wake him—who knew how long he’d stayed up to comfort her last night?

Susan found a chair and sat, too weary to go somewhere else and too afraid to be alone. As soon as she sat, everything from last night rushed back into her and she trembled. Susan curled into a ball.

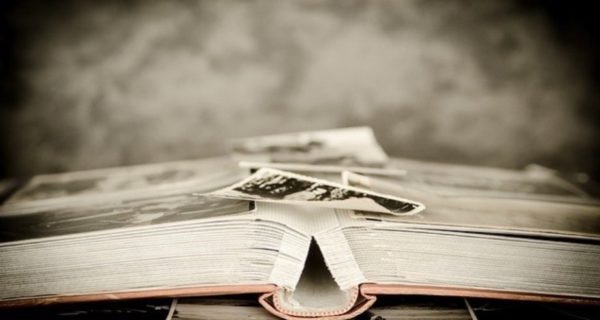

She would have hidden her head and dwelt on her pitiful future, but then she saw Peter’s book.

Peter, so kind and smart, a rock she’d taken for granted and even thrown away at times. How she missed knowing him as fully as she did when they were children.

Tears blurred her vision, but Susan reached for the book by Clives Staples Lewis. This time she did not think it boring, but lovely, as if letting her see into her brother’s mind for a short while.

And for that short while, she nearly forgot that they were all dead. The words of the author pulled her into an allegory of a young man running away from his Master because of his anger.

Just like her.

No, not like her. Aslan wasn’t real. He couldn’t be …

The young man, John, saw a beautiful island and wanted to go to it. However, every time he traveled toward it, he would be sidetracked by something that promised the same satisfaction to him. But the satisfaction was short-lived, and finally he wondered if the island he saw was even an island, but a fantasy in his mind.

But then John met a beautiful lady named Reason. He told the lady that he couldn’t believe in what he desired most—to reach a magical island—because there was a chance it was all his imagination.

“‘But I must think it is one or the other.’” Susan read John’s words to herself, feeling as if he said her own words.

“‘By my father’s soul, you must not—until you have some evidence. Can you not remain in doubt?’”

“‘I don’t know that I have ever tried.’”

And Susan didn’t know if she ever had. She had been angry at Aslan for taking Narnia away from her forever and for making her a child again. But also, as she grew up in the real world, the memories and even her anger had faded. She hadn’t wanted to doubt, she only to believe something tangible. And it had been easier to believe what she saw now.

Susan read further on into the book. John nearly decided to give up on his island, because so far everything he’d experienced had left him feeling dirty and defiled. The Island couldn’t be real—but even if it were, he was now certain it couldn’t be what he wanted. Then John met Wisdom, and his words took Susan’s breath away:

What does not satisfy when we find it, was not the thing we were desiring. If water will not set a man at ease, then be sure it was not thirst, or not thirst only, that tormented him: he wanted drunkenness to cure his dullness, or talk to cure his solitude, or the like. How, indeed, do we know our desires save by their satisfaction? The Desired is real just because it is never an experience. When do we know them until we say, “Ah, this was what I wanted”? And if there were any desire which it was natural for man to feel but impossible for man to satisfy, would not the nature of this desire remain to him always ambiguous?

Was this why life never satisfied? Had she, perhaps, lowered her standards to a lesser thing and settled herself to be satisfied in the world’s definitions of what was practical and real?

Susan finished the book.

It aroused every discomforting thought and she knew not what to do. She looked up and found Carl staring at her. “Have you been awake long?”

“Yes,” he said. “But you looked peaceful reading that book. I didn’t want to disturb you.”

Susan smiled. “It’s … one of Peter’s books. I’m surprised I even read all of it.”

Susan’s smile died away as she thought of Peter.

Carl left the couch and leaned over Susan, kissing her head. “I’m famished. I’m surprised the maid hasn’t brought us tea.”

“I told her to go home,” Susan said.

“Ah.”

And with his words, Susan realized just how inappropriate things would look to an outsider that Susan was alone in her home with a man.

“Why don’t we go out and buy a lunch?” Carl suggested.

Susan jumped from her seat too hastily, placing the book back where she’d found it. But before they could even put on their coats and hats, the front doorbell rang.

Susan answered the door and saw several policemen holding tattered suitcases. Susan knew at once that they were her family’s. Susan didn’t want to have to deal with any of it. Thankfully, Carl was just behind her and he took charge, showing the policemen where to put the things.

“And here’s a box that was found in one of their coats,” a policeman said. He handed an old cigar box to Susan.

“Thank you,” she said.

She waited until the policemen were gone, then Susan opened the box. Green and yellow rings lay folded between handkerchiefs. Susan stared, unsure of how to feel.

“What are they?” Carl asked.

“Rings,” Susan answered.

“I can see that.”

Susan said, “I’m sorry—I just don’t know how to tell you without making my family or myself sound insane.”

Susan barely noticed how she spoke of her family as if they still lived. It seemed impossible that they weren’t. Feeling weary, Susan leaned against the wall.

“I won’t ever think you’re insane.” Carl reached to Susan and stroked her hair. “Tell me if you want, or don’t if you want, but I’m here to help you in your time of loss.”

Susan gulped. It would be nice to tell someone. “When I and my siblings were staying with Professor Kirke during the war, we thought that’d we’d found a magical land inside a wardrobe. We all grew up in that land to be great kings and queens.”

Carl laughed.

Susan looked away.

“You’re not serious, are you?”

“I know now that we must have pretended—but at the time, it was hard to not believe. My siblings never stopped believing and were angry when I wouldn’t talk about Narnia with them anymore. And it was hard, Carl, to stop believing. Sometimes I still doubt. And Aslan … He was the hardest to forget. He’s … He was … He is hard to describe, but the most wonderful thing I ever knew. It was as if He were God, or so I thought. When I at last stopped believing in Him, I found I no longer could believe in God.”

Susan spoke slowly but knew that she needed to tell all of this to Carl. He would understand, she hoped. Or maybe he’d judge? And that was why she spoke solemnly and slowly.

Carl wrapped his arms around Susan. “Susan, you act as if you’re confessing to me. There’s no sin in a child having an imagination. And there’s no sin in that child growing up.”

“But what of what I said about God?” Susan murmured.

Carl laughed, “Don’t worry—I’m sure if He’s real, all He cares about is how good you are. And Susan, you are the best woman I know.”

But Susan felt as if she were merely a shadow of who she had once been. Parts of her gentle nature remained, but those parts were more self-focused and lacked depth.

Susan was not consoled by Carl’s words. In fact, her guilt was only intensified.

“Shall we go find food now?” Carl said.

Susan nodded. “And then can we go see my cousin?”

“Are you sure you’re ready for that?”

Susan put the box of rings into her purse. “Yes, I should have gone last night. I’ve been selfish.”

[Some material in this chapter has been quoted from The Pilgrim’s Regress by C.S. Lewis.]